This is the ninth post in a series on Yemeni dress, customs, and craft written by guest contributor Darleen Wilkerson Karpowicz, an American art teacher who lived in Yemen for five years in the early 1980s. During this time Darleen documented and studied the costume, customs, and crafts of the people she learned to love.

A wedding procession in Yemen in the 1980s

Indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. workshops

Indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. and other older dresses of Yemen were not easily found when I was living there in the 1980s. As Jebel Sabir style dresses and other more regional colourful dresses have shown us, Yemeni women love to wear colour and liked to display their own village-style dresses when possible. Yet, before these colourful dresses were available most women wore very plain garments customarily made from

indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. -dyed cotton produced in small dyeing workshops throughout the country. When I was there, only a few such workshops were left, located on the Tihamah. One or two small workshops were located in Sana’a producing only made-to-order

indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. dyed cloth. The long history of Yemenis wearing

indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. -dyed garments had mostly died out years before I arrived in Yemen in the early1980s.

An old

indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. -dyed dress from the Kholan area

Indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. dyeing

In days gone by, men would have been involved in the making of

indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. -dyed cloth. The men I interviewed in the Sana’a suq talked about the high demand for

indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. dyed cloth in the past and how business was strong and active. Up until the 1930s men and women all over Yemen wore

indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. -dyed clothing and headgear. The dye was considered to be a healing agent which could cure all ills, keep the body warm, and eliminate pains in the joints. Dyeing locally produced cloth had been the custom as importing cloth into Yemen was very restricted.

Indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. dye was not colourfast and gave a bluish tinge to the skin of the person wearing the dyed cloth. This was considered effective as a sunscreen and softening keeping the skin supple. As

indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. cloth fell out of favour it was common for the women to choose imported fabrics from which the colour ran as they thought the positive effects on the skin would be the same as from

indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. .

This

indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. -dying process was time-consuming as an alkaline solution needed to sit for three or four days before the cloth was dipped into it. The cloth then needed to be dipped into the dye solution for three days to obtain the strongest take of dye. After the cloth dried it was pounded with a heavy wooden mallet or was repeatedly scrapped on a smooth slab with a straight edge to produce the much desired metallic sheen characteristic of

indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. -dyed cloth.

Sana’ni dyers only performed this craft for special individual orders which mostly came from northern tribesmen. The

indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. dye itself came from Germany although in the past it was obtained from plants growing in Wadi Bayhan, historically known as a source of

indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. and

indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. -dyed cloth.

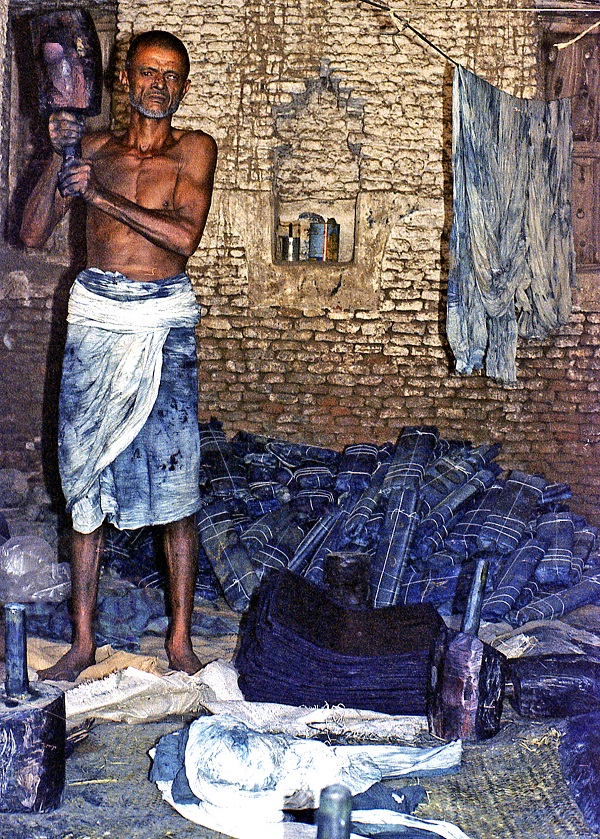

A worker at an

indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. -dye workshop in Tihama

Historical indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.

Older samples of the

indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. -dyed dresses were not easily found as many village women told me they 'were old and torn so we threw them away'. Many women spoke of their mothers or grandmothers wearing the

indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. -dyed black

qamis

Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

for everyday wear and the striped

ochre

Ochre: (Greek: ōkhra – Yellow Ochre), is a natural earth pigment that ranges in colour from yellow to red-brown, often used in art and decoration. -coloured

qamis

Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

for weddings and other special occasions. These dresses were thought 'to belong to the Iman’s time' and represented 'the old ways'. They were not worn and had not been worn in the cities for possibly fifty years by the time I lived in Yemen. In the outlying provincial areas, women had not worn them for some time making these dresses hard to come by, even as historical examples. The hand embroidery on these garments varied and sometimes included shells, small round metal pieces (used as sequins), buttons and other decorations.

A Yemeni wedding dress dating back to the time of the Imam

Wedding dress

I bought this yellow dress during my stay in Yemen. I was told it was a wedding dress. Yemen has very diverse wedding customs and practices in different parts of the country. This dress is from a time before women could choose a 'western' style wedding dress. The people that I talked to about this dress told me it was often worn by brides living in Sana’a mostly before the demise of the autocratic ruler, Ahmad bin Yahya. During his long reign, Yemen had little connections to the outside world and styles of dress were slow to modernise.

This dress is an example of a long-ago style that originally used material from Damascus, Syria. I was told that in days of old the women liked this material so much that Iman Yahya built a small factory where they would weave this heavy material. This particular dress is unique in that it has a decorative piece of cloth hand-sewn onto the inner sleeve of the garment. I was told this was for good luck and to keep the evil eye away from the bride and groom.

The sleeves of this garment are especially wide and during the wedding, the bride would have a woman friend pull back these sleeves and tie them in the nape of her neck producing a puffed effect for the sleeves. The added embroidered and sewn on tassels gives this dress an extra special look. This garment is said to be around ninety years old. It was probably never worn again after the wedding as it looks like new.

A wedding celebration outside Sana'a

Wedding customs

Yemen's diverse wedding customs meant what was allowed and preferred in Taiz was not the same as for a wedding in a faraway village in the north or even in the capital city of Sana’a. However, some customs were universal. All weddings would have had men and women separated during the customary three days of celebration.

Freya Stark, the famous British traveller who spent time in the Middle East during the 1920s observed that women were often covered with silver jewellery amounting to as many as twenty or thirty pieces. Such lavishness was not so common when I was in Yemen, but women still favoured an abundance of gold jewellery. The men in the jewellery shops in Taiz informed me that a woman was better served when her marriage contract was explicit in stating exactly what would belong to the bride and what she was allowed to leave the marriage with, in case of divorce. Technically, I was told, the law allowed a variation of arrangements regarding bride payment and rules of divorce.

About the Series

Read

Part 1,

Part 2,

Part 3,

Part 4,

Part 5, Part 6,

Part 7 and

Part 8 of this fascinating series here. The next post will be the last in this ten-part series where we will look at the contemporary dress of what was then North Yemen.

Further Reading

Marjorie Ransom: A specialist on Yemeni silver jewellery and author of Silver Treasures from the Land of Sheba

Sigrid van Roode: Jewellery historian and author of Desert Silver, and Silver & Frankincense

Author, Darleen Karpowicz

The Author

Darleen Wilkerson Karpowicz is an artist and designer who went to Yemen in 1981 to start an art department at a private Yemeni school. While working in Yemen for five years she met and married her husband (from England) and since that time together they have lived and worked in many developing countries for the past 33 years. Darleen worked predominately in the Middle East, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia with mostly Muslim women training them how to adapt their traditional textile-making skills to the modern market.

Copyright to all images belongs to Darleen Wilkerson Karpowicz. Reproduced here with permission.