This is the first post in a series on Yemeni dress, customs, and craft written by guest contributor Darleen Wilkerson Karpowicz, an American art teacher who lived in Yemen for five years in the early 1980s. During this time Darleen documented and studied the costume, customs, and craft of the people she learned to love.

My first introduction to Yemen

In the early 1980’s I was lucky to have received an invitation to be an art teacher at a private Yemeni school in Taiz which was then in what was known as the Yemen Arab Republic. The unification with the then People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, which occurred in 1990, had not come about yet. When I lived in Yemen for five years and as foreigners, we were not allowed to visit the south of the country.

It has been my passion, since a young girl, to study and appreciate ethnic textiles, costume, and the people who made and wore these. I had travelled to many countries in Southern Asia and the Far East during my years after college. So, when the wonderful opportunity for a job in Yemen arrived I was thrilled and responded “Yes!” immediately - even though I knew little about the country and the people which I came to know and love.

The terraced fields in rural Yemen Image: Darleen Karpowicz

The terraced fields in rural Yemen Image: Darleen KarpowiczThe geography of Yemen

Yemen is located in the southwestern extremity of the Arabian Peninsula, bordered by the Red Sea on the west, Oman to the east, and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to the north and east. The name Yemen is believed to have derived from the word 'ymn', the Arabic root word for prosperity, the country being named so because of its predictable and abundant rains in many parts of the country and bountiful agriculture grown in terraced fields.

Yemen is a country of spectacularly jagged high mountains, deeply incised by fertile and well-watered wadis as well as eroded river beds with terraced fields, high mountain plains, and deserts. The coastal plain - the Tihama - is hot and humid and is a predominately semi-arid cut across by wide wadis fed by waters from the mountains to the east.

As the plane from Cairo descended, I could see these deeply eroded wadi beds crisscrossing the mountains forming deep gorges which acted as barriers to travel and communication. One reason why Yemen had remained so isolated from the outside modernising world and why it was a haven for traditional culture, which had existed for centuries and still evident when I arrived.

A Yemeni woman going about her daily chores. Image: Darleen Karpowicz

A Yemeni woman going about her daily chores. Image: Darleen KarpowiczExploring Yemen

Once on the ground and after I had been teaching for a few months, I started exploring the city of Taiz and its surroundings. The first thing I noticed was that there was a large variation in how the women of Taiz dressed. Some were covered, some were not, some wore all black, some wore colourful dresses with pantaloons. It was fascinating! Early on I realised that to appreciate the women and their lives I would have to understand who wore what, where, and why. This approach led me over the years to begin to understand women in their society and their local culture. The variations that I saw, in the beginning, were overwhelming, seeming to deny any common thread. But, slowly and with time, and the help of my 3

rd and 4

th-grade girl students I started to figure it all out.

Darleen with her pupils who taught her to speak Arabic. Image: Darleen Karpowicz

Darleen with her pupils who taught her to speak Arabic. Image: Darleen KarpowiczLearning from my students

The girls in my art classes were my main teachers of the Arabic language. They brought me my first Arabic language textbook, titled “Abbi Saleh” printed in Egypt and used in all Yemeni primary schools to teach literacy. While I taught children art, the girls and boys in my classes also taught me basic spoken Arabic. I loved this way of learning through baby steps to build up my working vocabulary. I knew that if I could not ask simple questions and understand the answers I would never learn about the culture around me. I slowly started to learn the Arabic alphabet and then moved on to how to say basic things to the women as I asked them about their dresses. Who made their dresses; how old a certain design was; what their mothers wore before the current locally-favoured styles and fashions? My last question to the women who I talked with in the Taiz souqs and bazaars was always what village they came from and where it was located. Many folks from surrounding villages came to Taiz to shop and if I wanted to see more about their dresses and learn how they were worn I would have to visit them in their villages.

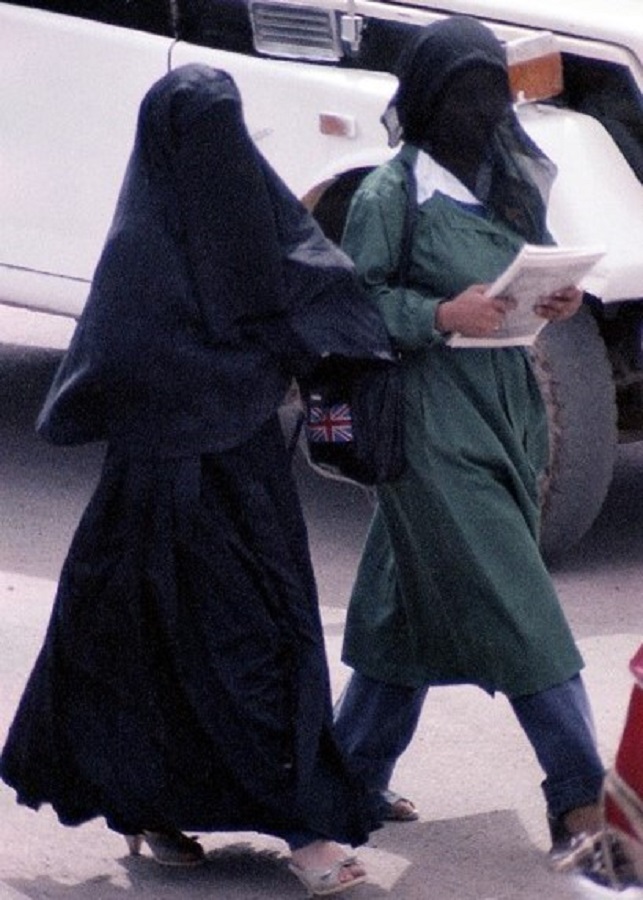

Yemeni women going about their daily chores. Image: Darleen Karpowicz

Yemeni women going about their daily chores. Image: Darleen KarpowiczCoverups

In the city of Taiz, there were a number of different types of coverups worn. The

sharsaf (a black skirt,

scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head., and veil ensemble that covers the entire body.),

abaya, and

baltow were the ‘modern’ form of coverups worn during my stay in Yemen. The sharsaf, seen in Taiz was worn throughout Yemen and was thought to have originated from Turkey. The abaya originated in the Arabian Gulf. In Taiz, it was worn mainly by women of Adeni descent, women coming from families who had lived in what was the Protectorate of Aden before the British pulled out and Aden city - in the 1950’s the fifth busiest port in the world. The southern part of Yemen fell under Soviet influence to become the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen. It was considered an elegant style by modern Yemenis. The same with the baltow, which looked, to me, a lot like a British “Burberry” raincoat. It was also worn mainly by women who had a connection to Aden. Then there were various other black cloaks and other covering garments seen around Taiz and its surrounding areas. Yet, there was also a large group of women always visible in the markets and streets of Taiz on daily errands, shopping and selling. These women wore many versions of coverups and many were often seen with none at all.

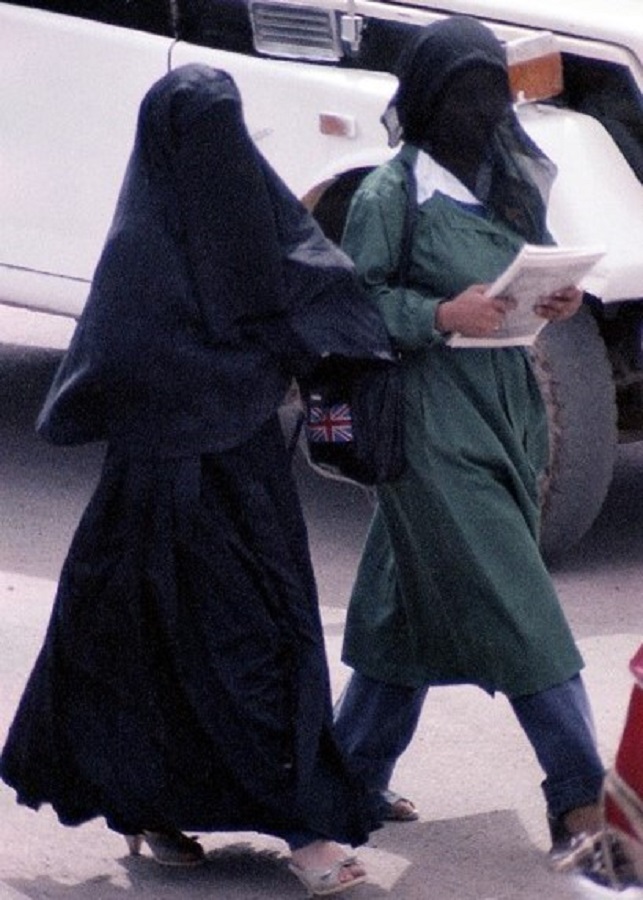

Yemeni woman on the streets of Taiz. Image: Darleen Karpowicz

Yemeni woman on the streets of Taiz. Image: Darleen KarpowiczWomen’s work

The women living in and around Taiz were always busy shopping, selling their produce, or going on errands for the family. These women were not confined to their homes, nor were they accompanied by another family member on their daily tasks. They were a large part of the city’s citizenry and the streets were filled with them walking briskly from their homes to the old souq and back again a few miles to their homes in the outskirts of Taiz where they lived.

I used to sit on the balcony of my apartment after school and look down at the busy streets and I was always astounded at how many different varieties of dress I witnessed and on how unhindered, self-confident, and strong these women must be. The women were always fascinating to watch and were variously and interestingly dressed, yet there was one very special and outstanding group of women who, although part of this crowded hurly-burly of women, instantly stood out from the crowd by dress, ornamentation and manner. These were mountain women from Jabel Sabir.

Jabal Sabir

Taiz is located at the foot of Jebel Sabir which dominates the skyline. The mountain summit is over 9000 feet above sea level and until the 1970s was accessible only by a footpath and donkey tracks. Jebel Sabir women were some of the most adorned, colourful and haughty women in the country and defied anyone’s stereotypical conceptions of what might be possible for a woman in a strictly traditional Arab country. They had a central place in the local economy as they owned land on which they grew the family’s qat crop, picked it, transported it down from the mountain, and sold it in the souq in Taiz. Qat is a mildly narcotic and highly addictive leaf that was chewed daily by most men and women during their afternoon socialising with their family and friends – women and men held these rituals in separate locations. Sabir women were also known to sell the mountain-grown papayas. Many of them spent much of their time in the city’s gold market talking and shopping with their friends.

Next post

In

the second post, we are exploring these women’s dress and look at a few other groups of women to be seen in Taiz and its surroundings. You will see a vast variety in what one might think of as customary Arabic women’s attire. We will take a magical trip to see the women of Jebal Sabir.

Author, Darleen Karpowicz

Author, Darleen KarpowiczFurther Reading

Marjorie Ransom: An specialist on Yemeni silver jewellery and author of

Silver Treasures from the Land of ShebaSigrid van Roode: Jewellery historian and author of Desert Silver, and Silver & Frankincense

The Author

Darleen Wilkerson Karpowicz is an artist and designer who went to Yemen in 1981 to start an art department at a private Yemeni school. While working in Yemen for five years she met and married her husband (from England) and since that time together they have lived and worked in many developing countries for the past 33 years. Darleen worked predominately in the Middle East, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia with mostly Muslim women training them how to adapt their traditional textile-making skills to the modern market.

Copyright to all images belongs to Darleen Wilkerson Karpowicz. Reproduced here with permission.

The terraced fields in rural Yemen Image: Darleen Karpowicz

The terraced fields in rural Yemen Image: Darleen Karpowicz A Yemeni woman going about her daily chores. Image: Darleen Karpowicz

A Yemeni woman going about her daily chores. Image: Darleen Karpowicz Darleen with her pupils who taught her to speak Arabic. Image: Darleen Karpowicz

Darleen with her pupils who taught her to speak Arabic. Image: Darleen Karpowicz Yemeni women going about their daily chores. Image: Darleen Karpowicz

Yemeni women going about their daily chores. Image: Darleen Karpowicz Yemeni woman on the streets of Taiz. Image: Darleen Karpowicz

Yemeni woman on the streets of Taiz. Image: Darleen Karpowicz Author, Darleen Karpowicz

Author, Darleen Karpowicz