This is the third post in a series on Yemeni dress, customs, and craft written by guest contributor Darleen Wilkerson Karpowicz, an American art teacher who lived in Yemen for five years in the early 1980s. During this time Darleen documented and studied the costume, customs, and crafts of the people she learned to love.

Jiblah

An interesting, picturesque, small town nestled in the sheltering foothills leading up to the neighbouring mountains. Trickling streams were in abundance, and as Jibla was also a small agricultural area, crops of maize and millet could be seen growing. It was an hour-and-a-half drive from Taiz yet it had a different ambience. It was a conservative small village and for me, it was a place to visit to see women and their dress in a less urban environment when compared to Taiz. It was the capital of Yemen many hundreds of years ago, and home to the only queen to ever have reigned over the country: Queen Arwa.

It was also known for having beautiful architecture with an old mosque that was said to hold the remains of the past queen. It was a good place for me to roam around the lanes and talk to the women to ask questions about their dresses. Sometimes I was asked in for tea and other times the women and I just chatted overlooking the beautiful valley.

Covering up

The women of Jiblah were mostly seen wearing various coverups but mainly the all-enveloping black sharshaf, which was the main coverup in Yemen and could be seen throughout the country. This consisted of a long black pleated skirt that hid every part of a woman except her feet, a black cape that rested on her shoulders, and two layers of chiffon covering her head and draped to the ends of her wrists. In Yemen, a person could tell who they meet on the street by looking at the woman’s feet.

In many large towns, women started wearing a coverup later in life than what was often expected in smaller towns and villages like Jiblah. It was not uncommon to expect young girls at eight years old to start wearing coverups in these less urban areas as these locations were much more traditional than larger cities like Taiz and Sana’a.

Dress Modern

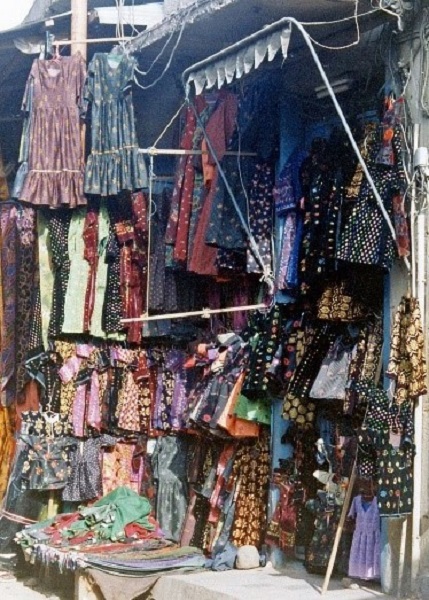

On my various visits to Jiblah, I was often invited into local homes for tea and then I could see exactly what the women of this area wore under their coverups. I saw that most women in Jibla wore a dress I named ‘the universal dress of Yemen’. The Yemenis called it the ‘dress modern’ and in the marketplace it was known as the ‘Zina’, meaning beauty. This garment replaced the fuller, longer, shapeless dress (ghamis), which had long, wide sleeves, no waist, was fully cut, and often indigo-dyed. In days gone by this universally worn ‘old’ dress of Yemen was what most women wore. Once this dress started dying out, the Zina dress took its place and it could be seen in many cities and towns throughout Yemen, north to south and in between. Wherever there was a large gathering of women one could see the Zina dress being worn by many.

Regional styles

The Zina dress style could be seen in virtually all areas of the country and yet, in most parts of Yemen, many women continued to wear the dresses unique to the city or villages they lived in, hence the wide variety of unique, colourful, and inventive costumes found on display as one moved around the country. The Zina could be made from a variety of cloth dictated by what was available in the local market. For everyday dresses, a soft polyester was often preferred and for special occasion dresses, velvet or any other locally available fancy dress material was used.

This ‘universal’ dress, the Zina, was favoured by the Imams’ wives from mid last century and was reminiscent of dresses worn by many western women in the 1940s and 50s. Some say that it was Turkish influenced and others say the English brought the style to Aden and it was deemed modern and then became popular throughout Yemen. It was the most commonly worn dress worn underneath the sharshaf throughout Yemen except in the Tihamah.

Accessories

The accessories worn to accompany the dress differed in various parts of the country but could include headscarves, undergarments of similar style as the Zina, flowers behind the ears, and gold ornaments for those who could afford it. The dresses were freely available in the market areas of cities and towns as male tailors made them ready-made. This giving of multiples dresses was often included in a wedding trousseau and it was not uncommon for a bride to be given 10-20 of these dresses for a wedding gift from the groom’s parents.

Sirwal

The pants, sirwal, worn under the Zina were full-length, loose cotton or cotton-polyester trousers with tapered legs and attached to narrow tightly fitted cuffs. These cuffs were frequently embroidered by hand with simple designs consisting of flowers, border designs, and zigzag patterns in a chain stitching technique. As the sirwal became old, the cuffs were removed and sewn onto the new trouser legs. During my stay, most of the embroidery was done by machine and the habit to reuse the cuffs was disappearing as it was relatively cheap to have new sirwal cuffs made.

The cuffs of old were decorated much more elaborately when compared to the ones made when I was living in Yemen. There are reports of intricately hand-embroidered leggings which were prized by the women and would have been kept and thought of as heirlooms. These were often made by Jewish Yemeni women, most of whom left Yemen in 1949-1950 and after that, the level of embroidery diminished. By the time I arrived in Yemen in 1981 all one could see of these treasures were in the suq stalls aimed at tourists and selling for very high prices.

Gargūsh

Often the girls and young women wore small hats called gargush (qarqūsh) which were a pointed variety in the north of the country, and a rounded crown style with a small ruffle around the face in the south. The old gargush were the most interesting as their styles and needlework combinations were limitless yet these were hard to find as handwork declined and simpler garments were being made in local mass-producing shops.

One of the first places I saw the Jiblah-style gargush, the ‘sun flower’ hat, was in Jiblah. The hat I first saw was worn by a young girl and was typical of the style favoured in the southern part of the country. It was a munchkin type of affair; gathered at the top and assembled around the face and tied under the chin surrounding the child’s face with ruffles that gave the impression of a sunflower.

However, little boys would sometimes also be dressed in this style of hat allowing their mothers to disguise them as a girl so that the evil eye would not harm them. According to custom, the evil eye was more prone to harm little boys, not being much interested in the girls. Additionally, small children were often painted with kohl which was sometimes smeared around their eyes to make the eyes prominent, like the centre of a flower.

Protecting the children

Kohl was used to protecting the child from the evil eye, so wearing a sunflower hat and also decorated with kohl markings around the eyes doubly protected small children from harm. In addition, I often saw children with charms sewn or pinned over their clothing which was believed to add extra protection and to save the child from harm. Folks believed that a dusty child was safer than one who was very groomed so often the small children in smaller villages were quite unkept. However, having been in the homes of numerous women throughout my five years in Yemen most of the time the children were well kept and groomed and clean once inside the house.

Read Part 1 and Part 2 here. In Part 4 of this series, we visit Jebel Habashi to learn more about the silver-sequined dress.

Further Reading

Marjorie Ransom: An specialist on Yemeni silver jewellery and author of Silver Treasures from the Land of Sheba

Sigrid van Roode: Jewellery historian and author of Desert Silver, and Silver & Frankincense

The Author

Darleen Wilkerson Karpowicz is an artist and designer who went to Yemen in 1981 to start an art department at a private Yemeni school. While working in Yemen for five years she met and married her husband (from England) and since that time together they have lived and worked in many developing countries for the past 33 years. Darleen worked predominately in the Middle East, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia with mostly Muslim women training them how to adapt their traditional textile-making skills to the modern market.

Copyright to all images belongs to Darleen Wilkerson Karpowicz. Reproduced here with permission.

Latest Comments

POST YOUR OPINIONThe women from Sana'a and Saad'a - The Zay Initiative

November 18, 2021[…] Turkish domination and was adopted in Yemen during the Iman’s times. We discussed this garment in these two previous […]