This is the eighth post in a series on Yemeni dress, customs, and craft written by guest contributor Darleen Wilkerson Karpowicz, an American art teacher who lived in Yemen for five years in the early 1980s. During this time Darleen documented and studied the costume, customs, and crafts of the people she learned to love.

Sana’a

Driving north from Taiz to Sana’a, the capital city of Yemen, the scenery changes from mountainous to a flat dry basin where Sana’a is located. The capital is 9,000 feet above sea level and one of the oldest inhabited cities in the world. According to historians, it has been habituated continuously for over 5,000 years. It is a very dry environment with hot summers and cold winters. The architecture of Sana’a is world-renowned and a sight to behold. The people of Sana’a were proud of their historic city and when I lived there, I was often treated to a walk around the lanes by the local inhabitants living in the old town. They loved to show foreigners the views and all the wonderful shops that their area was famous for. Before the current war, Sana’a was given recognition by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. The old city was built from mud, much like Saad'a, the fabled city further north.

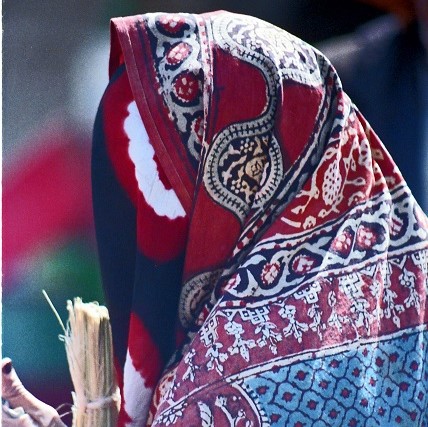

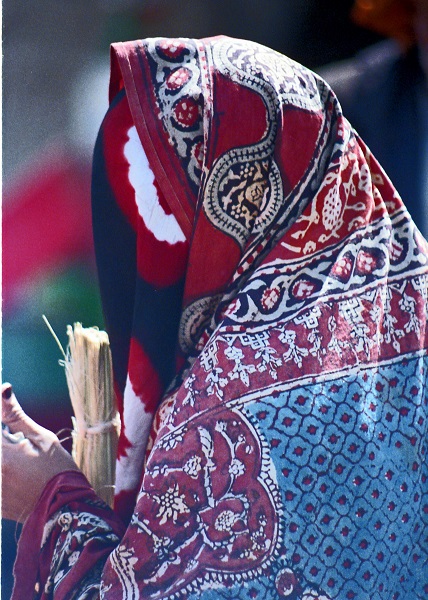

A woman from Sana'a wearing a

Sitarah

Sitārah: (Arabic: sitarah – to cover the woman from people's eyes when going out), a mantel that covers the entire body from head to toe, worn over clothes and often made of thick, colourful fabric, also known as an "abayah" or "mlayah" worn by Yemeni women in public particularly in Sana’ and its neighbouring regions.

and a Maghmukh

Dress Statutes in Sana’a

We do know that in the city’s early history and up until a few hundred years ago, statutes existed covering social events, including marriages, limits to bride prices, as well as other directives and ordinances restricting elaborate clothing and outlining what certain social strata of people should wear. According to local inhabitants these Sana’a statues at one time regulated clothing options for different classes making it obligatory to wear certain standards of clothing depending on one’s profession and occupation. Yet what was the norm for Sana’a was not necessarily accepted or even known about in other parts of Yemen. Rules were, most likely, localised since travel outside of one’s home area was not encouraged. All travel was difficult due to the harsh environment and topography. As a consequence, many areas could, and did, set their own rules and regulations on clothing and other social norms.

Embroidery detail on Ras Mukhmukh

Sitarah

Sitārah: (Arabic: sitarah – to cover the woman from people's eyes when going out), a mantel that covers the entire body from head to toe, worn over clothes and often made of thick, colourful fabric, also known as an "abayah" or "mlayah" worn by Yemeni women in public particularly in Sana’ and its neighbouring regions.

In general, most women in Sana’a wore cover-ups and the most commonly seen was the

sharshaf

Sharshaf: (Ottoman Turkic: çarsaf – bed sheet; Synonym: mlaya, mlyaya, sharsaf), a set of large cloth usually used as a body wrap by women in public.

- made of black cloth covering the entire body and face. This garment is thought to have been adapted during Turkish domination and was adopted in Yemen during the Iman’s times. We discussed this garment in

these two previous posts.

The

sitarah

Sitārah: (Arabic: sitarah – to cover the woman from people's eyes when going out), a mantel that covers the entire body from head to toe, worn over clothes and often made of thick, colourful fabric, also known as an "abayah" or "mlayah" worn by Yemeni women in public particularly in Sana’ and its neighbouring regions.

is a unique garment mainly worn in Sana’a and especially in the old city, as well as in the areas within the capital’s sphere of influence, and to the north of the country. It consisted of a piece of Indian-styled printed cloth approximately the size and shape of a bedspread. The one worn most often when I lived in Sana’a had a

paisley

Paisley: (Scottish Gaelic, Pàislig: a town in Scotland), often called buta, boteh, amli, or kalgi in the subcontinent and kazuwah in Arabic, is a Persian tear drop motif with a curved end specially in textiles. Its popularity and subsequent local production in 18th century at Paisley are responsible for its nomenclature. design with red, blue, green, and yellow patterns printed onto the cloth. Women in small towns outside of Sana’s preferred designs with different colours. During my stay in Yemen, this cloth had just started being printed in Sana’a, whereas previously it was printed and imported from India. The women were not impressed by the locally produced

sitarah

Sitārah: (Arabic: sitarah – to cover the woman from people's eyes when going out), a mantel that covers the entire body from head to toe, worn over clothes and often made of thick, colourful fabric, also known as an "abayah" or "mlayah" worn by Yemeni women in public particularly in Sana’ and its neighbouring regions.

material and they continued to purchase the Indian manufactured cloth.

The new cloth was stiff due to a finishing element ironed into the fabric during manufacture. As time passed by and it was washed a few times the cloth became soft and loose - it lost all its shape and consequently often just draped itself over the woman wearing it. The edge of the

sitarah

Sitārah: (Arabic: sitarah – to cover the woman from people's eyes when going out), a mantel that covers the entire body from head to toe, worn over clothes and often made of thick, colourful fabric, also known as an "abayah" or "mlayah" worn by Yemeni women in public particularly in Sana’ and its neighbouring regions.

was placed on the women’s head and she held it in front of her face with one hand.

Ras Maghmukh face veil

The majority of women also supplemented the

sitarah

Sitārah: (Arabic: sitarah – to cover the woman from people's eyes when going out), a mantel that covers the entire body from head to toe, worn over clothes and often made of thick, colourful fabric, also known as an "abayah" or "mlayah" worn by Yemeni women in public particularly in Sana’ and its neighbouring regions.

with a tie-dyed face veil, known as a maghmukh. It was woven in the Wasab region of Yemen on small hand looms and subsequently tie-dyed in red and black within the old city of Sana’a. This work was done in small workshops and sold nearby by shopkeepers. Worn underneath the maghmukh was the lithma which was often just a

scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. or piece of cloth the women sometimes used as an additional cover-up near the face.

Another interesting feature of the Sana’a face veil was that it was often accompanied by a ras maghmukh. In the days of old, the ras maghmukh was a hand-embroidered adornment that rested on the head. This piece was made by the individual women using mainly the

couching

Couching: (Latin: collocare – Place together), in needlework and embroidery couching is a technique in which yarn or other materials are laid across the surface of the ground fabric and fastened in place with small stitches of the same or a different yarn

embroidery stitch employing silver and gold metallic threads. Previously this embroidery was enhanced by the use of genuine

coral

Coral: (Greek: korallion, probably from Hebrew: goral – small pebbles), is a pale to medium shade of pink with orange or peach undertones, resembling the colour of certain species of coral. beads, but when I lived in Yemen they had been substituted by cornelian-coloured opaque glass beads. The older versions of this garment used to include pieces of heavy chain-mail metal-worked ornamentations. The combined embroidery, chain-mail, and base fabric created a very heavy headpiece that kept the maghmukh from slipping away.

Silver and amber jewellery in Sana'a

Amber Jewellery

When one walked around the old city of Sana’a most of the women were covered so it was not easy to catch a glimpse of the jewellery they might be wearing underneath their coverups. However, jewellery played a large part in the adornment of the women in Sana’a and other areas of the country. In times gone by the most cherished adornments were made of amber and silver. Yet, the amber that is and was famous in Yemen was always a little blurry since what was sold as amber in Yemen is not what many people today consider 'real amber'. This ‘real amber' came mainly from the Baltic Sea regions. A second category of amber that Yemeni buyers considered to be genuine amber were copal resins which are younger than Baltic amber (300,000 years old) but a natural substance and not man-made.

So, what is the amber that Yemen is so famous for incorporating into its traditional jewellery? According to books and the research that I did, Yemeni amber is artificial resins also called Bakelite. These were not produced in Yemen but rather were manufactured elsewhere and imported into Africa and Arabia maybe a few hundred years ago. The Bakelite imitations are so genuine looking and have been in the market for so long that many merchants consider them to be the real article and sell them as such. There are laboratory tests used to indicate real amber but an individual can also use a simple test: Real amber will float in saltwater and bakelite will sink.

The suqs of Sana’a were filled with the large square, cube-shaped, amber-looking beads, which the older women were still wearing when I lived in Yemen. These beads have been incorporated into the old traditional pieces of jewellery for hundreds of years and to the local people, they are amber. As a collector of Yemeni jewellery, these imitation amber necklaces represent long-established tastes and styles and their worth is not diminished by the fact that the resins are not forty million years old.

Women from Northern Yemen carrying baskets on their heads

The rural women of Saad’a

As one drives north from Sana’a in the direction of the border with Saudi Arabia one can see many small villages where families grow much of their own food in the harsh environment. It was not uncommon for grapes to be grown over vertically standing lava rock slabs to secure the grapevines. Some of these grapes were sent to be sold in Sana’a and the rest was used by the farming family.

Women could be seen along the small lanes as they attended to or bought vegetables, or carrying heavy buckets of water - needed for home consumption and washing clothes by hand at the village meeting place - on their heads. These were rural women and may not have ever been out of their small villages. Their clothing was usually a variation of the cover-up one would see in areas of Sana’a.

Some of these women made baskets by hand and sold them to travellers passing through their area or to local families who did not have the skills to make their own baskets. Basketmaking and spinning wool was a woman’s job and often rural women could be seen engaging in these activities as they sat outside their small homes to catch a cooling breeze. Due to the lack of customers, their production was not large. Yet, a little further along the road toward Saudi Arabia was a larger city, Saad’a, where the women were known all over Yemen for their colourful and beautiful baskets.

Basketmakers of Saad'a

The women of these northern areas lived a rural life. One that had been fraught with physical hardships, without modern conveniences until, if at all, only very recently before the current war. Volcanic cones, lava rock, and barrenness dominated the horizons of the country north of Sana’a. As you head further north along the road which eventually leads to Saudi Arabia the scenery changes from large level farm fields to the rock-strewn plateau where farmers are lucky to find enough land to cultivate. The few cultivated plots usually were bordered by stone watchtowers also used for storing produce, housing the farmers’ families when working in the fields, and acting as a defensive position against brigands and marauders.

Yet, it is in this rough and underdeveloped border city of Saad’a that we find an extraordinary group of women who made and sold their colourful baskets sitting on a hill outside of the town. As one meanders through the marketplace the women’s clothing was easy to see. Their clothing is not colourful and is very modest, however, they were able to sell in the marketplace on a daily basis. These northern women show us what they are made of. They had no modern conveniences. They lived in one of the most conservative areas in Yemen and yet they got out there and sold their baskets to foreigners and locals alike. Yemeni women are brave and strong and these baskets let us understand that beauty and strength are important to them.

About the Series

Read

Part 1,

Part 2,

Part 3,

Part 4,

Part 5, Part 6 and

Part 7 of this fascinating series here. In the next post, we will look at some of the older dresses worn by the women in Yemen before the hand-driven sewing machine arrived in the country at least 100 years ago. These dresses were made of

indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. and could have been very plain and utilitarian or they could have been made from brocades and included a lot of embroideries. The fabrics were often imported from Syria or Egypt. Some had embroidery and others were magnificent without embroidery. During this time the dresses were very different from what we have seen so far.

Further Reading

Marjorie Ransom: A specialist on Yemeni silver jewellery and author of Silver Treasures from the Land of Sheba

Sigrid van Roode: Jewellery historian and author of Desert Silver, and Silver & Frankincense

Author, Darleen Karpowicz

The Author

Darleen Wilkerson Karpowicz is an artist and designer who went to Yemen in 1981 to start an art department at a private Yemeni school. While working in Yemen for five years she met and married her husband (from England) and since that time together they have lived and worked in many developing countries for the past 33 years. Darleen worked predominately in the Middle East, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia with mostly Muslim women training them how to adapt their traditional textile-making skills to the modern market.

Copyright to all images belongs to Darleen Wilkerson Karpowicz. Reproduced here with permission.