Tallī: (Turkish: tel – wire, string), Gulf Arab – a woven braided trimming made with metal wire, threads and ribbons often sewn on detachable panels used as embellishments. Other – (Synonym: tulle_bi_talli

Tūlle_bi_tallī: (French: Tulle – a city in France where fine material for veil was first made; Turkish: tel – wire; Synonym: tariq; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the North African Arab region specifically in Egypt.

Tallī: (Turkish: tel – wire, string), Gulf Arab – a woven braided trimming made with metal wire, threads and ribbons often sewn on detachable panels used as embellishments. Other – (Synonym: tulle_bi_talli

Tūlle_bi_tallī: (French: Tulle – a city in France where fine material for veil was first made; Turkish: tel – wire; Synonym: tariq; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the North African Arab region specifically in Egypt.

Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

) worn by the local women could be seen.Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

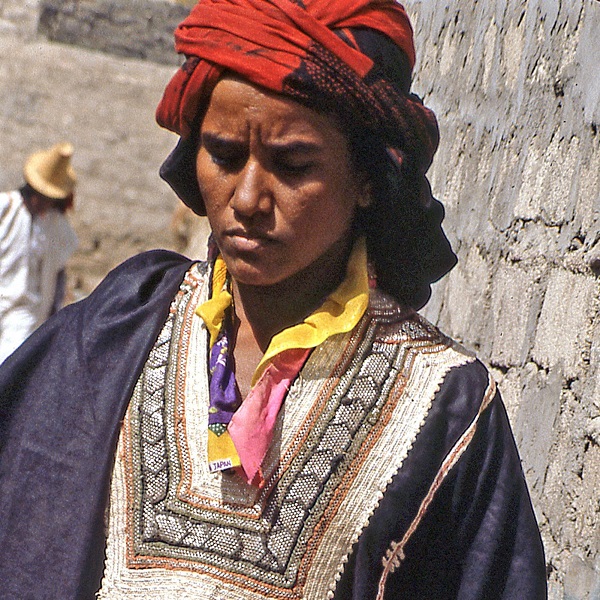

was especially unusual as it clearly displayed a combination of styles and designs previously mentioned as occurring in Bayt Bayt: (Arabic: house). Colloquially in the UAE it refers to the larger, middle part of the decorative ankle-cuff (bādlah) and can include between one to twenty different braids (talliTallī: (Turkish: tel – wire, string), Gulf Arab – a woven braided trimming made with metal wire, threads and ribbons often sewn on detachable panels used as embellishments. Other – (Synonym: tulle_bi_talli

Tūlle_bi_tallī: (French: Tulle – a city in France where fine material for veil was first made; Turkish: tel – wire; Synonym: tariq; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the North African Arab region specifically in Egypt.

Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

was loose and widely cut while it displayed the design, using tatting and silver metal thread embroidery (talliTallī: (Turkish: tel – wire, string), Gulf Arab – a woven braided trimming made with metal wire, threads and ribbons often sewn on detachable panels used as embellishments. Other – (Synonym: tulle_bi_talli

Tūlle_bi_tallī: (French: Tulle – a city in France where fine material for veil was first made; Turkish: tel – wire; Synonym: tariq; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the North African Arab region specifically in Egypt.

Tallī: (Turkish: tel – wire, string), Gulf Arab – a woven braided trimming made with metal wire, threads and ribbons often sewn on detachable panels used as embellishments. Other – (Synonym: tulle_bi_talli

Tūlle_bi_tallī: (French: Tulle – a city in France where fine material for veil was first made; Turkish: tel – wire; Synonym: tariq; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the North African Arab region specifically in Egypt.

Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

were frequently worn with the reverse side out apparently to keep the ornamentation clean but, according to one Bajil source, also to prevent prying and unwelcome eyes 'seeing the intricacy of the handwork'. Strangers seeing this intricate embroidery was considered bad luck to the owner and wearer of the dress.Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

were much more intricately adorned compared to some of the newer ones which could be seen more often towards the end of my stay in Yemen. Very traditional women used to wear this garment for a wedding dress and while I was there this style was dying out in favour of a newer more modern style of wedding dress with a more ‘Western’ look. While I was in Yemen, the traditional qamisQamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

were still being made and worn in and around Bajil and in Marawa which was a small town some twenty miles west of Bajil in the direction of Hodeidah.Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

are similar to those seen on the elaborately decorated face masks from the Hijaz region of Saudi Arabia as well as in parts of Ethiopia and Sudan. When questioned about the origin of this technique and designs people making these garments invariably stated that they were ‘Yemeni’. Yet, the women in Bayt Bayt: (Arabic: house). Colloquially in the UAE it refers to the larger, middle part of the decorative ankle-cuff (bādlah) and can include between one to twenty different braids (talliTallī: (Turkish: tel – wire, string), Gulf Arab – a woven braided trimming made with metal wire, threads and ribbons often sewn on detachable panels used as embellishments. Other – (Synonym: tulle_bi_talli

Tūlle_bi_tallī: (French: Tulle – a city in France where fine material for veil was first made; Turkish: tel – wire; Synonym: tariq; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the North African Arab region specifically in Egypt.

Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

was rather commonly worn and where it was sewn. Yet, Adahi was also a place where a more modern-day loose flowing ‘wrap’ appeared and many of the women in the area adapted this flowing garment as it was cool. The garment was decorated with machine embroidery for colour and design since its foundation was usually made from white or black material. This modern-day qamisQamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

seemed to have replaced the more elaborate hand-decorated article. Women in both Adahi and Bajil started wearing this garment in the early1980s years before I arrived in Yemen.Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

could be slipped over the head so no need for zippers or buttons. Garments that do not need zippers or buttons were preferred since these items were often impossible to find in the small local markets where so many of the population purchased their everyday items.

Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

made of white material were often embroidered with only black thread although sparkling metallic threads also appeared to be a favourite additional element.Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

were often worn with the standard Bayt Bayt: (Arabic: house). Colloquially in the UAE it refers to the larger, middle part of the decorative ankle-cuff (bādlah) and can include between one to twenty different braids (talliTallī: (Turkish: tel – wire, string), Gulf Arab – a woven braided trimming made with metal wire, threads and ribbons often sewn on detachable panels used as embellishments. Other – (Synonym: tulle_bi_talli

Tūlle_bi_tallī: (French: Tulle – a city in France where fine material for veil was first made; Turkish: tel – wire; Synonym: tariq; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the North African Arab region specifically in Egypt.