This is the tenth and last post in a series on Yemeni dress, customs, and craft shared by our guest contributor Darleen Wilkerson Karpowicz, an American art teacher who lived in what was then the Yemen Arab Republic from 1981 to 1986. During this time Darleen lived in Taiz, Ibb, and Sana’a, enabling her to collect information and widen her familiarity with different areas of the country and its people.

In this last post, Darleen shares a less structured and more life-like look at the women of Yemen, whereas in the previous posts she mainly shared images and stories focusing on single topics. As Yemen is so varied yet so unique in its dress, crafts and topography, mixing it up might give a clearer picture of how wonderful the people, clothing and embroidery was during her time in the country.

Examples of old and traditional embroidery in Yemen were scarce even back in the 1980s. It is not illogical, however, to assume that the art of embroidery was widely practised in earlier times as discovered textile and clothing remnants indicate. Embroidery techniques and materials are universal. Threads used for embroidery would have been, and still are, either of local production or imported. The origin of influences and ideas defining Yemeni embroidery can possibly be traced back to trade between Yemen, India, and Africa.

Embroidered Hizam

When I did my research there were small areas of Yemen where one could still see medium quality hand embroidery being produced and applied to the hizam, which is the main section of the traditional jambiyah, as well as onto hats made for religious men. Many men were still retaining the old tradition of wearing the jambiyah. These weapons were kept in a belt, or hizam, around their waist keeping this curved dagger and its sheath in place.

The belt was composed of a leather underside and intricately embroidered outer cover which was sewn to the leather to form the hizam. The belt traditionally had many uses, from hiding money to securing weapons. The old belts were all hand embroidered with some incorporating real silver and gold threads. In more modern times the threads were still silver and gold in appearance but made from metallic or synthetic materials.

An embroidered Hizam and Jambiyah

An embroidered Hizam and Jambiyah

The hizam, in modern times, were often machine decorated in Syria and then shipped to the marketplaces in Yemen. However, when I was there women and some men living in Sana’a still did some of this work. It was carried out as a cottage industry with the men and women sewing in their homes and the men delivering the finished product to shops as far away as Taiz and Hodeidah. According to local custom the hizam was once produced in the southern areas of the country but when I was there it was mainly produced in the north and later transported to outlying areas.

The motifs of the new belts were predominately curvilinear shapes forming a border with stylised flower patterns dominating the central field. Different quality belts were available with the older ones employing some of the best workmanship and design using a solid

satin

Sātin: (Arabic: Zaytuni: from Chinese port of Zayton in Quanzhou province where it was exported from and acquired by Arab merchants), one of the three basic types of woven fabric with a glossy top surface and a dull back. Originated in China and was fundamentally woven in silk. stitch to accomplish a filled-in area. This dagger was, and most likely still is, an important mainstay of men’s attire and yet women have for a long while been essential to its production.

Gawan

Gawan: (English: gown, or Arabic: qawan, synonyms: bīchī, fustān, nafnūf, kurtah

Kurtah: (Urdu and Persian: kurta, synonyms: bīchī, gawan, fustān, nafnūf, kirtah

Kirtah: (Punjabi: kurta, synonyms: bīchī, gawan, fustān, nafnūf), colloquially in KSA, Kuwait and Bahrain refers to sleeved, waist-cinched dress that comes in different styles.), a loose sleeveless shirt of varying lengths, typically falling either just above or somewhere below the knees, with its side-seams left open at the bottom, worn in South Asia, usually with a salwar

Gawan

Gawan: (English: gown, or Arabic: qawan, synonyms: bīchī, fustān, nafnūf, kurtah

Kurtah: (Urdu and Persian: kurta, synonyms: bīchī, gawan, fustān, nafnūf, kirtah

Kirtah: (Punjabi: kurta, synonyms: bīchī, gawan, fustān, nafnūf), colloquially in KSA, Kuwait and Bahrain refers to sleeved, waist-cinched dress that comes in different styles.), a loose sleeveless shirt of varying lengths, typically falling either just above or somewhere below the knees, with its side-seams left open at the bottom, worn in South Asia, usually with a salwar

Salwar: (Farsi: shalvār; Synonym: ṣarwāl, shirwāl ), trousers featuring tapering ankles and drawstring closure of Central Asian origin. They disseminated in the Indian subcontinent between c.1st-3rd century BCE. Although exact period of its arrival in the Arab world is disputed their widespread adoption is confirmed from the 12th century.

, churidars, or pyjama. In Hijazi dialect, the term refers to a sleeved, waist-cinched dress that comes in different styles, popularly worn since the 1950s., kirtah

Kirtah: (Punjabi: kurta, synonyms: bīchī, gawan, fustān, nafnūf), colloquially in KSA, Kuwait and Bahrain refers to sleeved, waist-cinched dress that comes in different styles.), colloquial term used in UAE for a sleeved, waist-cinched full-length dress of varying lengths and styles. hats and white scarfs in the marketplaceGawan

Gawan: (English: gown, or Arabic: qawan, synonyms: bīchī, fustān, nafnūf, kurtah

Kurtah: (Urdu and Persian: kurta, synonyms: bīchī, gawan, fustān, nafnūf, kirtah

Kirtah: (Punjabi: kurta, synonyms: bīchī, gawan, fustān, nafnūf), colloquially in KSA, Kuwait and Bahrain refers to sleeved, waist-cinched dress that comes in different styles.), a loose sleeveless shirt of varying lengths, typically falling either just above or somewhere below the knees, with its side-seams left open at the bottom, worn in South Asia, usually with a salwar

Salwar: (Farsi: shalvār; Synonym: ṣarwāl, shirwāl ), trousers featuring tapering ankles and drawstring closure of Central Asian origin. They disseminated in the Indian subcontinent between c.1st-3rd century BCE. Although exact period of its arrival in the Arab world is disputed their widespread adoption is confirmed from the 12th century.

, churidars, or pyjama. In Hijazi dialect, the term refers to a sleeved, waist-cinched dress that comes in different styles, popularly worn since the 1950s., kirtah

Kirtah: (Punjabi: kurta, synonyms: bīchī, gawan, fustān, nafnūf), colloquially in KSA, Kuwait and Bahrain refers to sleeved, waist-cinched dress that comes in different styles.), colloquial term used in UAE for a sleeved, waist-cinched full-length dress of varying lengths and styles. Hats

Women were also involved in making hats used by men for religious purposes. This tradition was dying out during my stay as mass-produced products were flooding the market. Yet, the merchants in the Sana’a suq sold these items and informed me that women were currently making the hats as they did in days gone by. This is an additional example of women being involved in embroidery production, even if it was much less important when compared to previous years.

It is a coiled hat similar to a pill-box hat. It sits on the men's heads looking like a coiled basket. The coils are woven and secured with beautiful coloured yarns in primary colours using acrylic yarn. Decorative geometric designs are added on top of the had using metallic looking threads.

When worn the hat is covered by a white

scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. meaning the gawas beauty is not actually seen. It is most often worn by the religious man, those learned in the Koran. This hat was most often worn in northern areas such as Sana’a, Thula, and Al-Hadtha. I was told the hats were made by families in those areas where they are worn and not elsewhere.

Gold and Silver

Women everywhere love gold and the Yemeni woman are no exception. In days of old and into the early 1970s silver was predominately worn and the techniques used in the production of

Yemeni jewellery were the same as those developed by the Sumerians, Egyptians, Myceneans, and other ancient cultures. The Yemeni craftsmen still used embossing and repousse to create patterns by beating or stamping the back of the metal. Chasing was the opposite where the design was formed by stamping the front of the piece hence the design was indented rather than convex.

Engraving the metal involved a tool to carve out the design creating hard indented lines. Granulation and filigree remained the most prized and time-consuming techniques creating the most valued and sought after items. Silver jewellery production was on the decline when I lived in Yemen as many of the expert craftsmen were Jewish and they emigrated to Israel in 1949-1950. Additionally, the older Yemeni craftsmen turned to work with gold rather than silver as women’s tastes were changing as they became more and more exposed to the modernising world.

Most of the gold jewellery was produced from gold bars imported into the country and later melted down and alloyed with small portions of brass to increase the gold’s hardness and durability. Pure 24-carat gold is too soft to make jewellery. Due to the investment and savings potential attributed to gold in the form of jewellery, Yemenis preferred a high gold content and most of the wearable items were made of 21- or 22-carat gold.

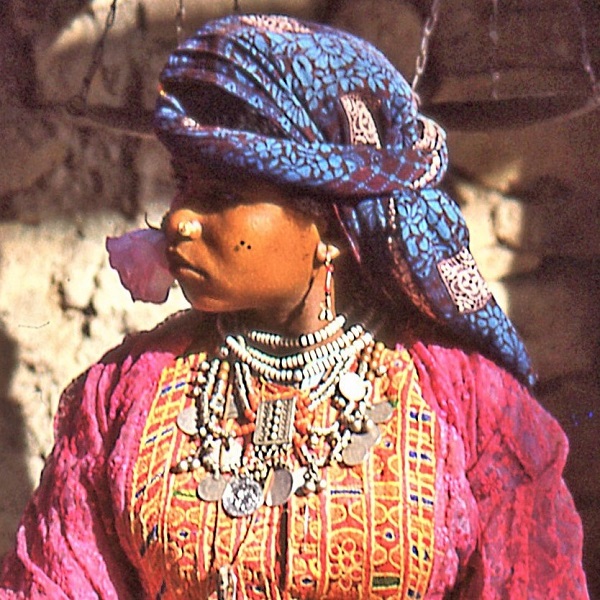

A woman wearing her wealth

A woman wearing her wealthDowry - a woman's wealth

I was informed that in Yemen, money, the so-called 'bride price', was given to the family of a bride by the bridegroom’s family. The marriage agreement was based upon a mutually agreed sum of money that the husband would present to the bride or her family in the form of gold jewellery and other items. These gold pieces formed a bank account for the woman and the gold received helped provide for a more secure future. The dowry a woman brought to the marriage included gold and other household items.

While I lived in Yemen, I married my British boyfriend. We were married in California and upon returning to Yemen all my little students gathered around me to talk about this news. The first day I returned to school all the little girls stood around me asking “Teacher, Teacher where is your gold?”

I lifted my arm showing them my one and only gold bracelet. Their faces showed me something was wrong. “No, Teacher, not that gold, that is old gold from before. We want to see the new gold that your husband gave you for your wedding present.” They could not understand how it was that I got 'nothing'. Even after explaining to them my western perspective, they talked about this endlessly, telling their mothers, and everyone in the school knew that I did not get gold for my wedding. The students gave my husband bad looks for months as they believed it was impossible that I received nothing from him on my wedding day!

At a party with Yemeni women, all of us bathed in frankincense

At a party with Yemeni women, all of us bathed in frankincenseScent and fragrance

An important aspect of a Yemeni woman’s life was scent and fragrance. The women loved to bathe themselves in the smoke from frankincense. Thousands of years ago, the raw ingredients for these exotic fragrances were harvested from trees and then transported from southern Arabia. The entrepreneurs of the time took huge risks moving northwards over the camel routes hugging the coast of the Red Sea. They travelled through Mecca and Medina and northwards. The Arab traders introduced aromatic essential oils to the west and these products of Arabia were prized and sought after. Rare oils, frankincense, and myrrh were pursued after and were a major part of the commodities carried on this 'Incense Road'.

During my sojourn in Yemen, these incenses were still very popular. A standard ritual during gatherings was to be smothered in their fragrance. The suqs were filled with many varieties of smells. Women ran small businesses in their homes making a mixture of scents and selling these in the local suqs. This was allowed and encouraged by the men since not all households could always afford pure frankincense. The manufactured scents from the suq smelled fabulous but were much cheaper than the real thing.

A 'working woman' wearing a heavily machine embroidered dress

A 'working woman' wearing a heavily machine embroidered dressWomen from the North and South

In this series, we have made our journey through what was then North Yemen. We have seen wonderful things and learned about women in various cities and small settlements. We have seen a wonderful collection of creative clothing, scarves, jewellery, and incense. Let me leave you with a beautiful woman wearing a heavily machine-embroidered dress. This was worn by a 'working woman' yet she is dressed in opulent attire. She might have had a little more money than the normal suq shoppers but she was not of the social elite. This type of dress was only seen in the southern part of North Yemen where the clothing was most flamboyant.

The illustration below shows us a typical woman’s attire found in the northern part of North Yemen. She is wearing a

sharshaf

Sharshaf: (Ottoman Turkic: çarsaf – bed sheet; Synonym: mlaya, mlyaya, sharsaf), a set of large cloth usually used as a body wrap by women in public.

which could be seen after leaving Taiz heading towards Sana’a and up until the border with Saudi Arabia. This garment is unadorned, yet it has a pattern and is attractive. That says a lot. Both of the garments are unique.

One woman is more embellished with decorative headgear and jewellery. The southern woman is much more flamboyant than our northern equivalent. But, our lady from the north has her attributes as well. She is strong, independent in that she walks sometimes for miles to fill her water bucket and to do the shopping for her family. She most likely works in the fields, fixes the meals and shops for the family needs. These are the extremes of Yemen.

A woman typical of the northern parts of Yemen

A woman typical of the northern parts of YemenConclusion

Now, with the war – what is next? My heart goes with the women of Yemen who allowed me into their lives and let me see their personal circumstances and ways of living that made them meaningful and special. May we all wish them well as these uncertain times continues.

Thank you to all who enjoyed my posts as I have enjoyed writing them and sharing my experience as I lived the Yemen

Arabia Felix for five years. May Yemen be happy and flourishing again soon.

Further Reading

Read

Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, and

Part 9 of this fascinating series here.

Marjorie Ransom: A specialist on Yemeni silver jewellery and author of Silver Treasures from the Land of Sheba

Sigrid van Roode: Jewellery historian and author of Desert Silver, and Silver & Frankincense

The Author

Darleen Wilkerson Karpowicz is an artist and designer who went to Yemen in 1981 to start an art department at a private Yemeni school. While working in Yemen for five years she met and married her husband (from England) and since that time together they have lived and worked in many developing countries for the past 33 years. Darleen worked predominately in the Middle East, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia with mostly Muslim women training them how to adapt their traditional textile-making skills to the modern market.

Copyright to all images belongs to Darleen Wilkerson Karpowicz. Reproduced here with permission.

In this last post, Darleen shares a less structured and more life-like look at the women of Yemen, whereas in the previous posts she mainly shared images and stories focusing on single topics. As Yemen is so varied yet so unique in its dress, crafts and topography, mixing it up might give a clearer picture of how wonderful the people, clothing and embroidery was during her time in the country.

Examples of old and traditional embroidery in Yemen were scarce even back in the 1980s. It is not illogical, however, to assume that the art of embroidery was widely practised in earlier times as discovered textile and clothing remnants indicate. Embroidery techniques and materials are universal. Threads used for embroidery would have been, and still are, either of local production or imported. The origin of influences and ideas defining Yemeni embroidery can possibly be traced back to trade between Yemen, India, and Africa.

In this last post, Darleen shares a less structured and more life-like look at the women of Yemen, whereas in the previous posts she mainly shared images and stories focusing on single topics. As Yemen is so varied yet so unique in its dress, crafts and topography, mixing it up might give a clearer picture of how wonderful the people, clothing and embroidery was during her time in the country.

Examples of old and traditional embroidery in Yemen were scarce even back in the 1980s. It is not illogical, however, to assume that the art of embroidery was widely practised in earlier times as discovered textile and clothing remnants indicate. Embroidery techniques and materials are universal. Threads used for embroidery would have been, and still are, either of local production or imported. The origin of influences and ideas defining Yemeni embroidery can possibly be traced back to trade between Yemen, India, and Africa.

An embroidered Hizam and Jambiyah

An embroidered Hizam and Jambiyah Gawan

Gawan: (English: gown, or Arabic: qawan, synonyms: bīchī, fustān, nafnūf, kurtah

Kurtah: (Urdu and Persian: kurta, synonyms: bīchī, gawan, fustān, nafnūf, kirtah

Kirtah: (Punjabi: kurta, synonyms: bīchī, gawan, fustān, nafnūf), colloquially in KSA, Kuwait and Bahrain refers to sleeved, waist-cinched dress that comes in different styles.), a loose sleeveless shirt of varying lengths, typically falling either just above or somewhere below the knees, with its side-seams left open at the bottom, worn in South Asia, usually with a salwar

Gawan

Gawan: (English: gown, or Arabic: qawan, synonyms: bīchī, fustān, nafnūf, kurtah

Kurtah: (Urdu and Persian: kurta, synonyms: bīchī, gawan, fustān, nafnūf, kirtah

Kirtah: (Punjabi: kurta, synonyms: bīchī, gawan, fustān, nafnūf), colloquially in KSA, Kuwait and Bahrain refers to sleeved, waist-cinched dress that comes in different styles.), a loose sleeveless shirt of varying lengths, typically falling either just above or somewhere below the knees, with its side-seams left open at the bottom, worn in South Asia, usually with a salwar

A woman wearing her wealth

A woman wearing her wealth At a party with Yemeni women, all of us bathed in frankincense

At a party with Yemeni women, all of us bathed in frankincense A 'working woman' wearing a heavily machine embroidered dress

A 'working woman' wearing a heavily machine embroidered dress A woman typical of the northern parts of Yemen

A woman typical of the northern parts of Yemen