This is Part 3 in a series on the dress and adornment from the Siwa Oasis, inspired by two items in the Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative’s Collection: a heavily embroidered traditional bridal tunic, called asherah nuhuwak (ZI500491 EGYPT), and two coloured silk braids, called legateen or liquatin (ZI500491a EGYPT), that are detachable decoration for the bridal costume. Read Part 1 and Part 2 here. Traditional bridal costume, asherah nuhuwak ZI500491 EGYPT via The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative Collection

Ancient Pharaonic Egypt

have been brought up numerous times in recent Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative webinars, including the talk on symbolism in Egyptian dress with Dr Andrea Rugh, and the talk on dress and identity with Shahira Mehrez. Both of these webinars, and many others, can be viewed by becoming a Friend of The Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period.. In this post, we will explore the possible connections between the Siwa Oasis, Amazigh tradition and history, and Pharaonic Egypt. Rock art in the Algerian Sahara with an example of the Tifinagh script used by the Tamazight language family. Picture via Wiki Commons

Language

Comparative Linguistics is a field of study that often sheds surprising light on ancient links between seemingly separate cultures. The people of the Siwa Oasis speak Siwi, which is included in the Tamazight language family that forms one branch of the Afro-Asiatic language group. This family of indigenous languages, spoken predominantly across the Maghreb, are mutually incomprehensible, yet share distinct commonalities. Since the introduction of Islam to North Africa, Tamazight languages have been influenced over time by Semitic languages which make up a separate branch of the Afro-Asiatic language group, and have thus adopted many Arabic loan words. Furthermore, Siwi also contains influences and linguistic connections to the ancient Egyptian language, which is yet a third separate branch of the Afro-Asiatic language group. This provides fairly concrete evidence for the likelihood of millennium-old connections between the first settlers of the Siwa Oasis and the Pharaohs. Image of the sun god Ra. Picture via Wiki Commons

The Egyptian Cult of the Sun and the Temple of the Oracle

In the Ancient Egyptian pantheon, many of the gods and goddesses were associated with the sun, each representing manifestations or attributes of this universal power. Yet Ra, with the head of a falcon and a sun disk resting on top, was often considered the main form for the god of the sun. The word Ra in Ancient Egyptian was synonymous with ‘sun’ and ‘day,’ he was believed to give warmth to the living body and was symbolised by an ankh, or 'key of life'. Ra took many forms and was known as a composite god who would often be melded together with other deities, resulting in a ‘solarisation’ of local and indigenous gods. By the New Kingdom, the god Amun rose to prominence and he was fused with Ra into the popular sun god Amun-Ra. In Ancient times the Siwa Oasis would have been known to the Pharaonic Egyptians along the Nile Valley as a place with an important temple dedicated to Amun-Ra. The still standing ruin of the Temple of the Oracle dates back to the sixth century BCE, but it was most likely built on top of an older Pharaonic temple dedicated to Amun-Ra, or the related ram-headed Libyan god Ammon. Many legends surround the founding of the temple, one claims priestesses from the Temple of Amun in Thebes were banished to the desert and thus founded a new cult still devoted to their Pharaonic god. Oracles were thought to be manifestations of the gods, able to see into the future and were thus consulted regularly before important decisions were made. The Temple was a symbol of the wealth and importance of the Oasis and was one of the most revered oracles in the ancient Mediterranean. Many rulers either sought its advice or sought to destroy it. The Temple of the Oracle remained popular during the Greek era, as the Greeks equated Amun-Ra with Zeus, there was even a direct boat from Greece to Marsa Matruh, then called Ammonia, where devotees would have begun their desert trek. Most famously, around 332 BCE the Temple was visited by Alexander the Great to ask if he was the son of Zeus. After his visit, Alexander adopted ram horns in his iconography, a symbol of the Egyptian god Amun, and it is suspected the answer was positive! Following the death of Cleopatra, the popularity of the Oracle declined during the Roman domination of Egypt, but the cult still coexisted with the introduction of Christianity to Egypt until the sixth century CE, when Emperor Justinian ordered the closure of all pagan temples across his Empire. The ruins of the Temple can still be visited today. Temple of the Oracle. Picture via the author, 2013

Indigenous North African and Arabian Solar Deities

Before Islam came to North Africa and the Middle East, many of the indigenous animistic belief systems contained some aspect of sun worship. There is no one pre-Islamic Amazigh belief system, different beliefs developed regionally, often influenced by neighbouring religions or traditions. While most Amazigh converted to Islam by the end of the seventh century, including in Siwa, some older beliefs continue to subtly exist in traditions and culture. The worship of the moon and the sun is thought to have permeated many of the pre-Islamic belief systems and was indeed described as the religion of the ancient Amazigh by both Herodotus and Ibn Khaldun. The ancient Libyans are also thought to have venerated the Egyptian sun deities of Osiris and Amun, which would possibly explain the presence of the Temple of the Oracle at Siwa Oasis, so far west of the banks of the Nile River. Dr Andrea Rugh mentioned in her webinar that the Siwan garments’ embroidery represented rays of the sun, either as a survival of the Ancient Egyptian sun worship of Amun Ra or because the Siwan people used to worship a sun god in their own indigenous religion. Most likely the sun symbolism is a product of the integration of belief systems, which combined both indigenous Amazigh animism and Pharaonic religion. Akhenaten worshipping his monotheistic interpretation of God in the form of Aten, represented by the Sun Disk. Picture via Wiki Commons.

The symbolism of the Sun

The distinctive embroidery on Siwan clothing is ripe with symbolism. On bridal garments, the motifs and materials are thought to promote fertility and protect the bride from the evil eye. Most of the symbolism alludes to an aspect of the natural world, specifically elements relevant to Amazigh daily life. The traditional embroidery threads are five colours: black, orange, yellow, green, and red. These colours represent the natural environment, signifying the desert sun and the ripening fruit of the date palms and olive trees. The rays of the sun are a predominant theme on many garments, often radiating out from the central collar. On bridal garments, including the one in The Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative’s Collection, the embroidery displays radiating patterns duplicating sun rays. The nacre buttons themselves are called tutintfukt in Siwi meaning the ‘eye of the sun,’ and they are an important talisman for the Siwan people since they reflect light and are believed to attract the energy of the sun, which is then transmitted to the wearer. Symbolism in dress is passed down from generation to generation, and often the history behind the meaning of the designs becomes lost and the design becomes the meaning in itself. Irrespective of their symbolic value, patterns were valued in themselves and perpetuated in ancestral legacies. the people absorb the meaning of the symbols subconsciously without knowing the origin of the symbolism. Sun rays feature predominantly on the asherah nuhuwak. Picture: The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative Collection ZI500491 EGYPT

Embroidery as jewellery

Shahira Mehrez mentioned in her webinar that the heavy embroidery around the neck opening of Siwan garments, called towqatayn, is a reproduction of the ankh (key of life) shaped embroidery on tunics found in the tomb of King Tutankhamun. The ancient Egyptians used coins to adorn their garments, both because they reflected light in the same way as nacre and because they were talismanic. Coins are often made of silver or a silver alloy. In Pharaonic times, silver was sometimes considered more precious than gold. Traditionally, in the Siwan Oasis, as among the Amazigh and Bedouin, silver was the metal of choice and worn as a form of ‘mobile bank.’

Interestingly, in one Siwan tunic in Shahira Mehrez's personal collection, silver coins were found stitched under large nacre buttons. She concludes that the interspersed light-reflecting nacre buttons on the embroidery of the tunics were probably a cheaper and more available replacement of the metal reflecting devices found in pharaonic costumes.

King Tutankhamun’s embellished coffin. Picture via Wiki Commons

Living relics of ancient tradition?

More connections between Siwa and Ancient Egypt can be made with the overall look of the garments the Siwan brides wear during the marriage ceremony. From surviving art, we can see that Pharaonic Egyptians favoured wearing clothing in white cotton or linen and often decorated with beads. This type of garment strongly resembles the white bridal tunic known as the asherah nuhuwak, and which can be found in The Zay

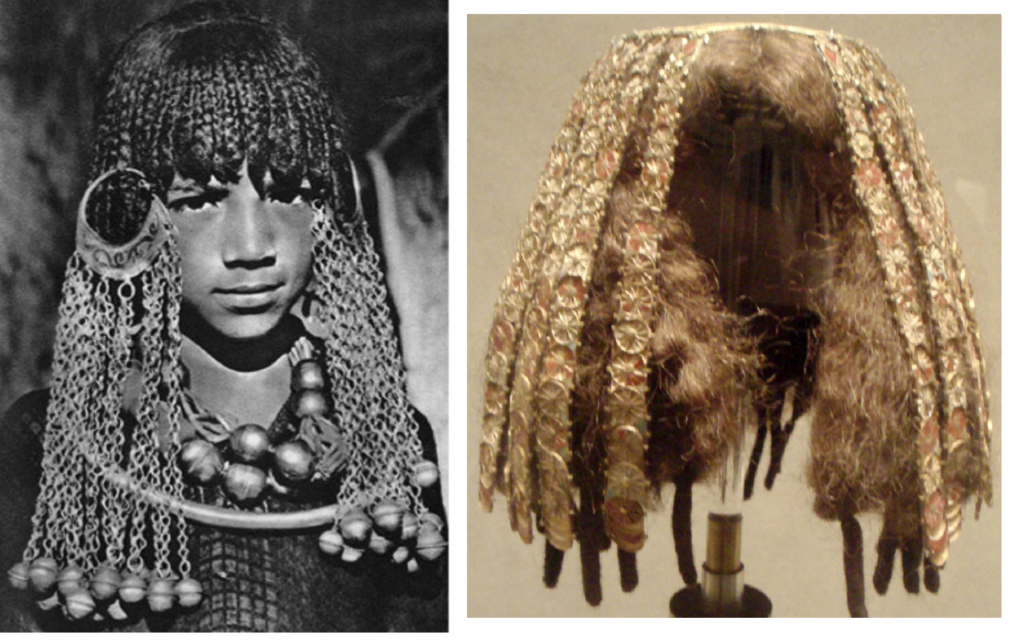

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiatives Collection. A headpiece was worn by unmarried girls, and last worn by brides during their wedding festivities is known as a tadlilt, made of a red leather headband from which hangs up to twelve leather straps, reaching to just above the shoulders. The hanging straps are decorated with amber beads, nacre buttons, coloured glass, or plastic buttons. Silver rings and bells hang on the ends. When wearing this headdress, the Siwan bride resembles wall paintings from Ancient Egypt. Tadlilt. Musée d’ethnographie, Geneva. Picture via Vale (2015) pg 199

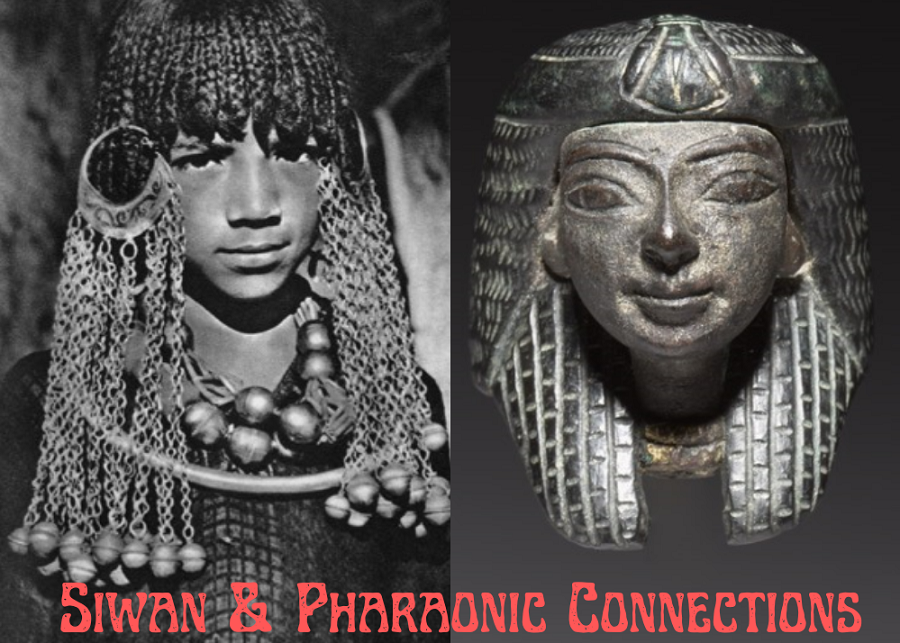

Left: Siwan girl with cushit hairstyle and silver adornment (1930s) picture: Marion Wasdell and Brian de Villiers, via Vale (2015) pg 124. Right:

Wig cover, an approximate recreation (from original pieces) from the tomb of three minor wives of Thutmose III at Wady Gabbanat el-Qurud, circa 1479-1425 B.C. Made of gold, gesso, carnelian, glass and jasper. Picture: Wikimedia Commons via Metropolitan Museum of Art Left: A sketch of a Siwan girl. Picture via Vale (2015)

Right: Egyptian head from Thebes. Cleveland Museum of Art Picture via Wiki Commons.

Further Reading:

- Bliss, Frank. 1998. Artisanat et Artisanat d'Art dans les Oasis du Désert Occidental Égyptien, Rüdiger Köppe Verlag Köln

- Bliss, Frank. 1998 Siwa: Die Oase des Sonnnengottees, Bonn

- Ethnographic Museum Geneva, 1986. Egypt: The Oasis of Amun-Siwa, Geneva

- Fakhry, Ahmed. 1973. The Oases of Egypt, volume one: Siwa Oasis. American University in Cairo Press, Egypt.

- Giddy, L.L. 1986. Egyptian Oases: Bahariya, Dakhla, Farafra and Kharga during Pharaonic Times. Aris and Philips, UK.

- Malim, Fathi. 2001. Siwa: from the inside. Traditions, customs, & magic. Al Kaatan, Egypt.

- Mehrez, Shahira. 2021. Egypt's Lost Legacies; The Costumes of Women in the Countryside, Oases and Deserts, Institut Francais D'Archeologie Orientale, (IFAO) Press, Cairo (to be released winter 2021)

- Vale, Margaret. 2015. Siwa: Jewelry, Costume, and life in an Egyptian oasis. American University in Cairo Press, Egypt.

- Vivian, Cassandra. 2000. The Western Desert of Egypt. American University in Cairo Press, Egypt.

The author standing in the Temple of the Oracle, 2013