On 27 April 2021, Dr Reem Mutwalli chaired a discussion with Shahira Mehrez about her outstanding collection of Arab dresses and regional Egyptian costumes. They spoke about the way in which the costumes in Mehrez’ collection could reflect the regional identity of the wearer, their socio-economic situation or their standing in society. After the discussion, Shahira Mehrez shared with Dr Sophie Kazan how this collection came about, the factors that have shaped her life and her collection. She described her childhood, her work as an academic researcher with one of the stars of Islamic architectural research, as well as the tense and colourful political backdrop in Egypt at the time.

You have described the tense period in which you grew up in the 1940s and 1950s – a tumultuous time in Egypt with the Arab Israeli conflict in 1948, the deposition of King Farouk, followed by the government of President Naguib, then Egypt rallying around Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser, followed by the Suez Crisis. Your family were landowners and it must have been hugely disruptive for a young girl at school… Can you describe what it was like growing up surrounded by all of this?

These were difficult times to live in, because having owned land, we were branded as ‘old regime’. The country was taking a turn to the left and by 1961, when the so-called ‘July Socialist Laws’ were promulgated. I was old enough to realise the ambiguity of my situation. On one hand, I was all for Arab Unity, justice for the Palestinians, and the Non-Alignment policy. I had read Dostoyevsky, Jack London, and Sartre, and was convinced that my ‘class’ had abused its privileges. So, I sympathised with many of the ideas of the revolution: (industrialisation, self-sufficiency, pacification, social security for the workers, land to the peasants, education for all…), but even if land reform could be justified, how could one accept nationalisations that often looked like personal vendettas or the arbitrary policy of expropriation and sequestration that left whole families with six pounds a month? The worst was the establishment of a police state, the reign of fear and the silencing of dissident voices.

It was with all these mixed feelings that I graduated from school in 1962. In my utter confusion one thing was clear: Like many other women of my generation, I owed my education to the revolution. ‘Women represent half of the society and have to work shoulder to shoulder with men’, was one slogan that I first thought was been effectively applied. In the new constitution, we were given equal rights and voting power. But why was Egypt’s leading feminist, Dorreya Shafik, under house arrest? The paradox was difficult to digest. Whatever the case, I was the first female member of my family to go to university. Ironically, the changes affecting our society had convinced my father - more effectively than I could ever have done – to prepare me to be independent, as it had become obvious that there was no security in pre-arranged traditional marriages. ‘Education is the only thing no one will be able to take away from you’, he often bitterly repeated.

Age six, between my cousin and my brother in the company of my first French governess, mademoiselle Cullet

What led you to explore your Egyptian or indigenous roots?

[At the American University of Cairo, during] …the last semester of my senior year, I took a course in Arab History with Dr Afaf Lutfi El Sayyed. ...I read passionately through our history, discovering the wealth of our culture and by the time I graduated in the summer of 1966, I knew what I wanted. An identity…. I decided to search for my roots, and, like Ulysses, I embarked on a long journey. It started with my mother’s graduation gift, a three-month tour of Europe that I felt I needed to cut the umbilical cord with my ‘French’ past. Today’s young Egyptians cannot realise how difficult it was back then, to travel out of the country…. You needed to be sponsored by someone living abroad, committing himself, in writing, to assume all the costs of your stay. The document had to be approved and duly sealed by the Egyptian consulate in the host country before being presented to the scrutinising eyes of the bureaucrats of the Ministry of Interior, fearing that you might be some kind of time bomb, going to the enemy and exploding to embarrass the regime.

Returning from my grand tour, I perceived Egypt with different eyes. I felt like a romantic tourist discovering thousands of years of a hidden civilisation. I could still see the discrepancies of the old and new regimes, all the right slogans that had gone wrong, but the bitterness was gone.

Our yearly winter holiday in Upper Egypt showing from left to right, on the front row my mother, myself at five, my brother and on the second row, a guide (?) my paternal aunt, my father and my Egyptian Jewish governess, Mademoiselle Sophie. She married two years later but her relationship with my mother was so strong that she always came back to her for advice and protection and spent more time with us than in her own home. Her departure in 1956 was a source of great sorrow to all of us.

When you returned, you decided to study Islamic Art. Did this make you feel closer to your Egyptian identity?

Yes, in the second semester of the academic year 1966/67, I went back to my Alma Mater [AUC] enlisting in the brand-new MA program in Islamic Art and Architecture. This is when I really learned to read Arabic, fighting through the medieval chronicles of Ibn Duqmaq, Al-Maqrizi, and Ibn Iyas with an Arabic/English dictionary in my hand. I was fascinated by Islamic architecture and I was discovering my native city, not the capital of Farouk or that of Gamal Abdel Nasser, but the Cairo of a thousand and one nights. I had wonderful teachers, Christel Kessler and Michael Rogers. I got along very well academically and socially with both. I still felt marginal and living in a cocoon, but my life was taking an interesting turn. Not only was my Arabic improving, but as I accumulated erudition, I could teach a thing or two to those ‘real’ Egyptians who, for so long, had labelled me a

khawagaya (a foreigner).

Professor Creswell was the “pope” of Islamic Art. His books “Early Muslim Architecture” and “The Muslim Architecture of Egypt” set the basis for this field of academic studies. They remain to this day very important referential works for architects interested in the Arab world as well as for Islamic art historians.

So, you began an academic career as a researcher for the illustrious Professor Creswell?

Professor Creswell was still alive, with all his books around him in the two rooms above

Oriental

Oriental: (Latin and Late Middle English Adjective: orientalis – From Orient; from Latin (noun): oriri – to rise; and oriors – East), anything of an Eastern origin in relationship to Europe – Asia. The word was first used in the context of territorialization between the late 3rd and early 4th Century CE. Hall at AUC. Christel Kessler was looking for a student assistant to fill his book orders, and to re-shelve volumes after each class - he did not want precious bindings to be spoilt by labels. She was also in need of someone to take care of the labelling and filing of the Islamic art slide collection. She recruited me and, for almost four years, I spent twelve hours a day working and studying in the little antechamber that preceded her office… We lived much more frugally then, as we were required to tighten the belt in order to build our country. There was a shortage of hard currency, imports were limited to the minimum, luxury items were inaccessible, and even locally produced consumer goods were sometimes in shortage as exports to the Soviet Union and the Eastern bloc were intensified to pay military bills…The real problem was elsewhere. Arab unity was proving hard to achieve. On the campus, we were making bitter jokes such as: “Who are the Arabs: people who like Umm Kulthum”. Cynically, it seemed that the ‘Diva’of Arab music was the only thing we had in common.

Attending a reception with Hassan Fathy

During your conversation with Dr Reem, you spoke about the influence and inspiration of the renowned architect, Hassan Fathy.

I was searching for him. My studies had made me proud of my heritage but had not solved the dilemma between my western education and my Egyptian background. Like me, he was a hybrid of two cultures but instead of being torn apart, he saw it as a blessing. His secret was to deepen our knowledge of both and chose what suited us best from each. To illustrate his point, he took me to the madrasa of Sultan Hassan and played Brahms on his violin: the great achievements of the two civilisations are complementary, he said, and there is no contradiction… The idea was simple and the demonstration magical and quite convincing. My ordeal was over, and the puzzle of my identity was gradually being pieced together.

On the left is a cross from a 20th-century tunic from Siwa in north-western Egypt, and on the right, the drawing from a similar pattern from a 4th-century excavation in Nubia in southern Egypt

Was it through him that you became increasingly interested in traditional Egyptian regional life and visual culture that existed outside cosmopolitan cities?

Hassan Fathy did more than reconcile me with my own culture. From our early childhood our parents had been very conscientiously taking me and my brother to all the archaeological and historical sites; since we owned land, I had been quite often to the countryside; we had camped in the desert and picnicked in all kinds of scenic surroundings. But in all these visits we never really mingled with the rural communities around us. We remained aloof as if we were tourists in our own country.

We lived in two different worlds, and I arrogantly had felt that ours was the more ‘developed’ and that there was nothing ‘these simple people’ could teach us… Hassan Fathy showed me what we owed to this other Egypt, that of unassuming peasants ploughing the land along the Nile, of shepherds roaming in deserts or settled in distant oases. While we, urban elites had shed our skin to imitate dominant cultures our present with our past: I discovered how vernacular architecture perpetuated age-old techniques and methods, they had, up to the end of the 20

th century succeeded in preserving our culture for us, thus linking of construction, and was introduced to a wealth of rural and Bedouin crafts rivalling artefacts preserved in museums. I was grateful and humbled...

My collections of traditional costumes and crafts were exhibited and presented in live shows in Egypt as well as in several European capitals

You have described how a little after this and after you were first married, you were accepted at Oxford to research for a DPhil, with much of your research taking place at the Egyptian National Archive – how was that?

The atmosphere at Oxford, as in Cairo, was extremely political. I felt terribly isolated working on the 14

th century. We were only a handful of Arab students, but the ones with whom I fraternised were all studying contemporary history. I regretted not having done the same. By the end of 1977, Sadat made his historical visit to the Knesset and in 1978 the Camp David agreements were signed confirming our fears of a separate Egyptian-Israeli peace. We were very much opposed, not because we wanted war, but because we thought that had we gone to the negotiation table as an Arab Block we would have had better chances in achieving a just and sustainable peace. We were right as time has proved that Camp David did not succeed in bringing an end to the Palestinian/Israeli conflict.

By the end of 1978, having finished most of my research I went back home to start writing but I had other worries. My marriage had collapsed, and I had to achieve financial independence. I was back teaching at the Faculty of Tourism, but my salary was barely enough to pay for house help. I refused to make money selling notes to students, a usual practice in Egyptian Universities. What was I good at? Back in the late 50s, I had started acquiring traditional costumes, first for fun, then as I grew older and developed an art historian approach, as a serious collector. Hassan Bey had also introduced me to another Egypt, one of the simple folks and their crafts. We had canvassed the countryside and the oases looking for whatever had survived of the great traditions of the past. I decided to start a craft shop making accessible to other women the dresses that, by now, I was wearing every day; I also felt I could have a role in slowing down the eradication of age-old skills.

Though at the time I only collected these items because they were beautiful and deserved to be preserved, I discovered while studying them they were more important than I had first thought.

Was this how you became a collector of Egyptian costumes and artefacts?

My studies of our past architectural achievements had played their role in my life, making me proud of my legacy and of my identity but they were far removed from our everyday realities; what I wanted now was to be dealing with an aspect of Egypt that was still alive and where I could make a difference. Eventually, as I had never enjoyed it, I gave up teaching and I devoted myself to what I liked most: researching, collecting, and promoting traditional crafts. I travelled throughout the country purchasing whatever artefacts I could find. I am presently convinced that I took the right decision as I succeeded in gathering – at the right time before they completely disappeared - what is now one of the most important collections of hitherto unrecorded Egyptian traditional costumes, jewellery, flatweaves, pottery, and baskets.

Though at the time I only collected these items because they were beautiful and deserved to be preserved, I discovered while studying them they were more important than I had first thought. Firstly. they could be directly tied to age-old artistic traditions. Secondly, as regardless of variations in proportions and techniques they all displayed similar symbols, they provided tangible and undeniable proof that irrespective of distant geographic locations, beyond religious and ethnic diversity, we were one Nation sharing the same heritage. Thirdly, the fact that these symbols were perpetuating Pharaonic, Coptic, and Islamic emblems melted down in one tradition, bore witness to the multicultural and pluralistic nature of our Nation.

Discovering the Thursday Bedouin souk in El- Arish.

How did you become involved in working with women’s regional textile and embroidery projects?

One day in 1979, two American women, Elaine Strite and Jayme Spencer, both of whom were to become good friends, came to the shop to show me the embroideries of a Mennonite-sponsored income-generating project established by Elaine in the then still occupied Sinai Peninsula. I was later invited to visit and before I knew it, in 1981, I was asked to take it over [Al Arish Needlework Project]. I had a lot of hesitations, never having worked in development, but I felt ashamed to refuse without trying.

When I had visited their workshops in El Arish I had been impressed by their dedication and the fact that to help people they had nothing in common with, they had sacrificed their comfort, living in extremely frugal conditions in a country that was not their own! I could do not do less…

Therefore, I started spending one week a month in El Arish. For a long time, the women there led me to despair, all they knew from us inhabitants of the valley were the often-corrupt bureaucracy and they resented me for replacing Elaine. At the end of the two years I had given myself to succeed or fail, they suddenly, without warning decided to accept me. From that time onwards we established a strong relationship of mutual trust and in the decade to follow the project grew as a cottage industry giving work to hundreds of Bedouin women.

How did you then become involved in extensive agricultural projects and learn about food production?

My second husband, Renaldo Tommasi, was Italian and though an engineer by profession, was dreaming of having his own olive orchard and making his own olive oil. He bought a concession of some 500 hundred acres of desert land and embarked on land reclamation… The first years, as we were the only project in the middle of the desert, we were raided by Bedouins who wanted to sell us in the morning what they had stolen from us the night before. The police were helpless (or conniving…) and we had to organise our own militia to guard the land… The plantation was large and included some 40 0000 trees; when, after five difficult years they started to flower, it appeared that we had been given an assortment of different varieties, each displaying a different stage of maturity. I was at a loss as at harvest time, it is essential to know how many trees can be harvested to assess the manpower required for the task. A young Italian expert, Aldo Biondi, working with the Italian Cooperation saved me. He helped to identify the trees and we discovered that over and above the seven varieties my husband had required we had been given thirty different ones… To be able to harvest I had to draw charts for the 520 acres where every variety was represented by a symbol within a small square. It took me three years to complete the job, but it allowed us to harvest efficiently and rapidly…

Within a few years, in spite of all the challenges, our orchard became one of the best in Egypt, and the olive oil we produced came to be considered by many experts as one of the best in the world. This however was not the end of my troubles as I had to deal with market fluctuations, the rapacity of wholesale dealers and the often irrational decisions of the different ministries …

When your beloved husband died, you decided to sell this project that had been his project really and decided to go back to visual culture and your original interest in fabric and costumes. Was it easy to go back to city life?

The country was in crisis, as instead of the promised affluence, the open-door policy adopted by the government starting with the Sadat Era, had set the ground for unscrupulous investors. The medieval city, already threatened by decades of mismanagement and growing pollution, was left at the mercy of real estate speculators and its urban fabric seriously damaged by demolitions and disfigured by offensive high rises. State factories suffering from mismanagement were privatised, but instead of being upgraded their machinery was sold as scrap iron and their buildings pulled down to take advantage of rising land value; thus a skilled working class numbering hundreds of thousands faced unemployment or joined the masses of unskilled labour.

The long fibre cotton, for which Egypt was famous, was disappearing due to faulty agricultural strategies. For the first time, I had difficulties in finding the fine cotton cloth that for over a century had been our pride and glory. Gradually, textiles produced in other parts of the world, China, Korea, and Turkey started to invade the market. This affected me as I felt strange using imported fabric to produce traditional costumes !!! I was also confronted with the toll to be paid for my lack of regular visits to El Arish and the growth of the income generation project came to a standstill.

However, what was happening on a national scale was more serious than any personal difficulties. There was an obvious erosion of the middle class and the gap between rich and poor had grown to outrageous proportions. From 2006 onwards discontented but peaceful protesters with different demands regularly disrupted the traffic of the main streets of large urban agglomerations. With the exception of Mehallah El Kobrah, the centre of the Egyptian textile industry, these gatherings were not very large. In spite of that, they were considered a threat by the police state and were always brutally repressed, thus exacerbating resentments and adding to the unrest.

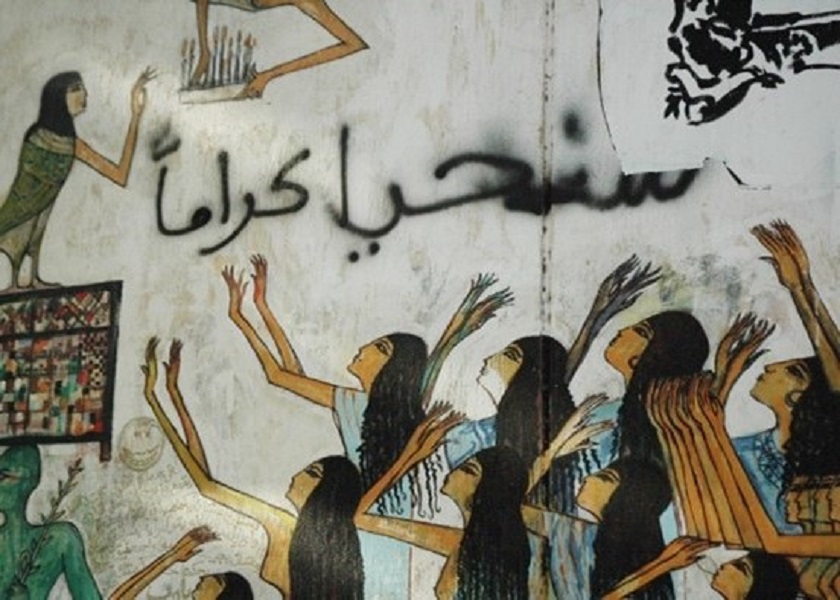

The graffiti of young revolutionary artists on wall surfaces around Midan El Tahrir were telling the story of the Egyptian people: Their glorious past and their sad reality…their confrontation with a brutal world that gave them little hope, their sudden awakening to the possibility of change, their fears and anxieties dreaming of a better future.

And so, you joined the demonstrations!

I went back to my old habits and joined the demonstrations taking place in Cairo and Alexandria. For years it really seemed that our contestations were not leading us anywhere until, finally, in January 2011, the volcano erupted, and millions were in the streets.

The crowds were calling for the drafting of a new constitution, the end of an abusive regime, social justice, and dignity for all. Their first request was to elect from among well known political figures a president of the republic who could fulfil their aspirations. Parliamentary elections were to come as a second step to allow the people to get acquainted with the candidates who were going to represent them. Unfortunately, what the military council ruling the country imposed was an amendment to the old constitution followed by a parliamentary election. This was a disaster, as thousands presented themselves for the job and it meant that, apart from some well-known figures in Cairo and Alexandria, the people in the different governorates had to vote for someone they did not know. This also meant giving the country to the Muslim Brotherhood, the only organised sector that had successfully grown in the shadow of the previous regime… During their year-long rule, they attempted to undermine existing institutions and threatened all our cultural values; when they were finally ousted by the second wave of massive popular revolt, due to the absence of organised political civilian leadership we fell prey to the same totalitarian regime we had been trying for so long to shake… Thus, the peaceful revolution of the Egyptian people was twice aborted and we returned to the status quo!

The graffiti of young revolutionary artists on wall surfaces around Midan El Tahrir were telling the story of the Egyptian people.

Around Tahrir Square, the young revolutionary artists had graffitied the walls. What did you see?

These were telling the story of the Egyptian people: Their glorious past and their sad reality… their confrontation with a brutal world that gave them little hope, their sudden awakening to the possibility of change, their fears and anxieties dreaming of a better future.

Thank you so much for sharing your fascinating journey that is so embedded in the modern history of Egypt and that weaves together its traditional and modern history so intricately. It is so interesting and important to appreciate the context and motivations behind extensive art or artefact collections such as yours. We thank you very much and look forward to reading about these events in more detail in your memoirs, which hopefully you will be publishing soon!

****

About the Author

Sophie Kazan fell in love with Islamic Art and decoration after visiting the Louvre in Paris and she enjoys exploring the materiality of objects and cultural paradigms. She studied Art and Archaeology of Asia and Africa (BA Hons), completing her Masters in History of Art and Archaeology (University of Oxford) and researched how tradition and modernity are represented in contemporary art by Emiratis (School of Museum Studies, University of Leicester). Sophie enjoyed talking to Andrea Rugh about life in the UAE, Egypt and Saudi Arabia and how many cultural beliefs and philosophies are translated into clothing and traditional dress. Learn more about Sophie’s work on

her website and

Instagram profile.

Read Sophie's interview with Dr Andrea Rugh

here.

**All images supplied by Shahira Mehrez