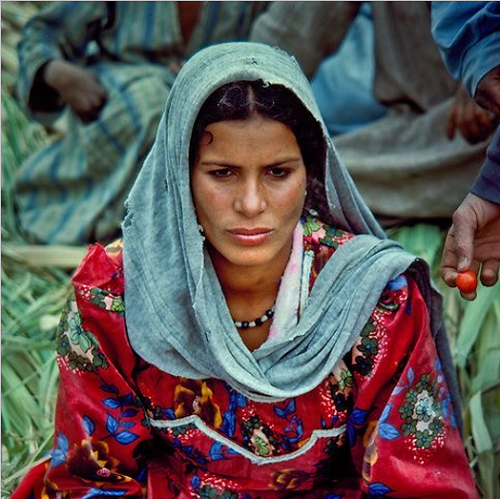

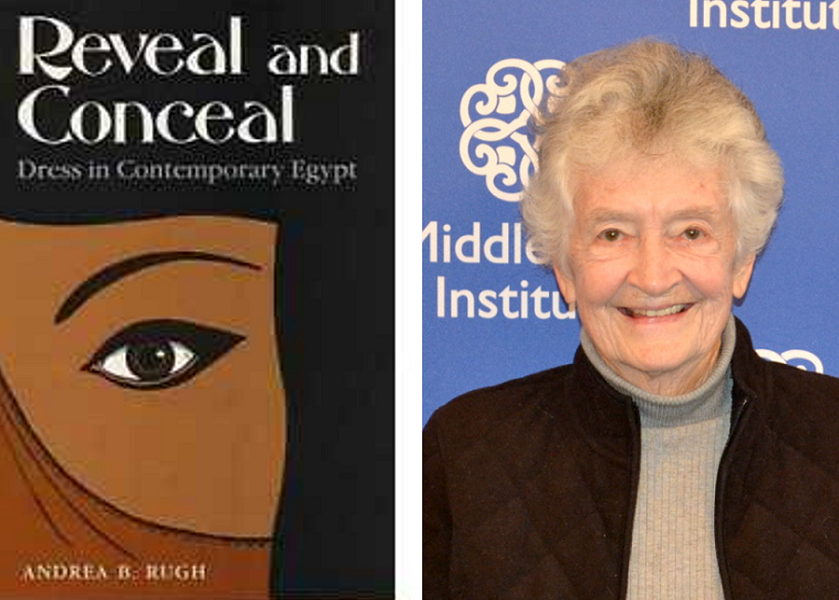

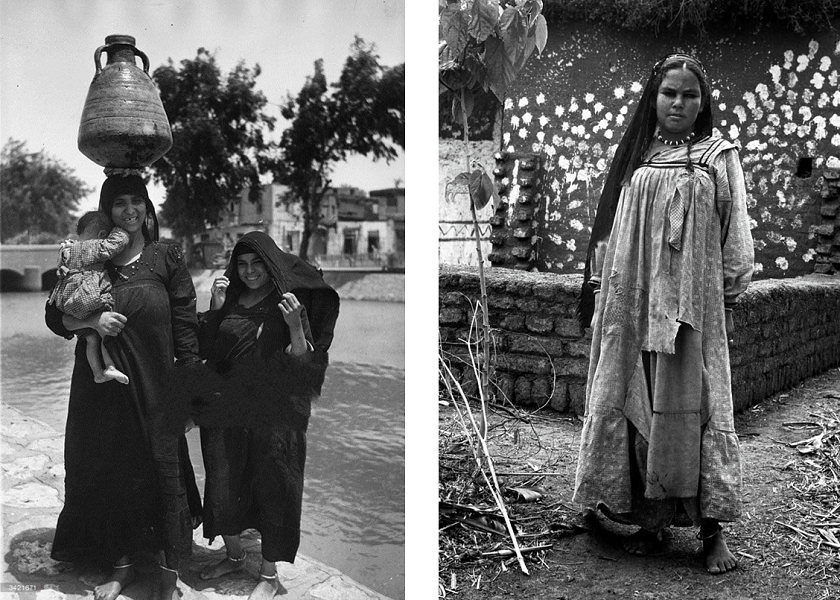

The Anthropologist Dr Andrea Rugh spoke to the Zay Initiative in March with Dr Reem Al Mutawalli moderating. She spoke about her book, Reveal and Conceal and about geographical variations in Egyptian women’s traditional dress and symbolism that she has come across in her anthropological research. Dr Sophie Kazan spoke to her about her experiences living in the MENA region and how dress has evolved over time.

SK: Thank you so much, Dr Rugh, for agreeing to share your observations with us today. You have described the different regional styles of dress in Egypt at length but also note that in more modern times, these regional modes of dress have mostly disappeared except in an occasional older woman. Young, educated men and women now opt for Western or Islamic modes of dress.

AR: Yes it’s true that older people sometimes cling to older fashions in dress but now it is rare to see examples of these even in older women. Think about it, people now buy ready-made dresses or if they still have dresses made to order, they no longer can find tailors or seamstresses who know how to make older styles. Also, most of the younger generations go to school and want to show they are educated and modern and not uneducated rural people who wear the styles I described. These younger educated women are more likely to wear hijab and Islamic dress and even those who wear the so-called Western dress would probably like to think of it as an “international” style. The wording is sensitive. In Egypt, Christians are more likely to wear this international style as a way of showing their international connections. They especially signal these links when they feel stressed, while at times of Egyptian nationalistic sentiment they mention their Pharaonic connections as original Egyptians.

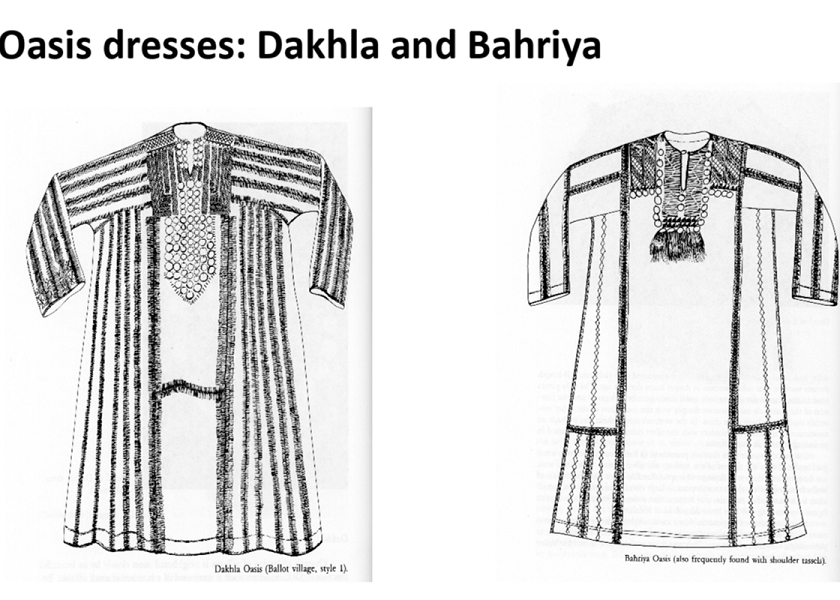

SK: Do you feel that regional styles are in danger of being lost? Is that why you had them hand-drawn in a detailed manner?

AR: For the most part regional styles are already gone. I had my friend Buffie Rodenbeck draw the dresses because the details were not showing up in photographs, especially when the background material was black.

SK: Please describe your doll project – where you asked village women from areas to make and dress dolls in the local styles and tell us where the collection of these dolls with Egyptian traditional costumes ended up.

AR: I had the dolls made through Shahira Mehrez’s projects for village women. It was important to me to obtain well-constructed examples of the regional dresses. Village seamstresses sewed dresses of varying quality—often poorly constructed or of cheap fabric–while Shahira’s women produced good quality ones. The dresses and dolls are now in the Maryland Art Institute but are not on public display—rather students study them. I did not think at the time that these styles would be lost so quickly… but certainly, if there ever is a question of finding the dolls an alternative home, I will think of the Zay Initiative.

SK: What do you see as replacing the idea of dress as a national identifier or signifier? Are we going to see a more global and a more equal mode of dressing amongst the sexes generally that is less nationalistic or regional and more to do with the individual? If so, where does this leave ideas of tradition and modernity, young and old?

AR: The identifiers in Egyptian dress that I saw in the 1980s no longer reflect what is important to Egyptians. Now it is more important to show class level. The vast majority in the younger generation—rural and urban—want to be seen as educated and middle class. Educated women now are thought to make better wives and so they want to be seen as having workplace skills that make them more marriageable. With widespread, free education, the lower classes are quickly joining the middle class and when they do so signal the change by wearing styles that reflect their new status (international dress or Islamic dress). The hijab is a useful transitional style for the lower classes—it shows women have the marriageable traits of education and modesty. Village identity is no longer important. The upper-middle and upper classes on the other hand distinguish themselves by the quality and style of their dress that tend to adhere to international fashion. These of course are gross generalisations that have lots of exceptions.

SK: In the past, you have spoken about the role of the anthropologist and much of your research helps broaden cross-cultural understanding. What could be done, do you feel, to ensure that the study of people, their cultures and dress are more broadly acknowledged, for example in foreign policy and diplomatic relations?

AR: I feel very strongly that anthropology no longer plays the role it once did in helping the public understand cultures. We used to see our job as developing cultural insights for both scholars and the general public. But the Margaret Meads and Ruth Benedicts no longer exist. In their place anthropologists focus mostly on library studies or brief field studies on narrow topics that they report in a jargon only scholars understand. This stultifying scholarship may be a reaction to criticisms that anthropologists base their conclusions mainly on single cases and anecdotal evidence rather than more “secure” statistical studies. This is unfair since earlier methods required intensive and lengthy periods spent with their subjects, digging deeply into their beliefs and social organization. This goal is different from statistical knowledge but was often a way to understand the numbers.

I believe qualitative studies are necessary to understand a culture and regret the new emphasis on theory and library work. Amazingly, anecdotal material doesn’t seem an obstacle in political science when its members speculate on future events and are often wrong. Surely the old types of anthropological studies were more grounded in their conclusions.

The good news is that many scholars now come from the region. When I was starting the majority were foreigners and admittedly some wrote with a certain amount of Edward Said’s Orientalism, maybe not so much intentionally as because as foreigners their access was limited. The bad news now is that these young local scholars are often inducted into the cultures of their disciplines in Western universities where, as I have said, they learn to approach topics in a theoretical and fragmented way rather than contributing to the public’s understanding. This is an important reason we know so little about other cultures and tend to measure them ethnocentrically by our values.

SK: Though you focus on dress in Egypt in your book, Reveal and Conceal, you have also lived in Saudi Arabia, Syria, Yemen and the UAE and Lebanon. My research into Emirati decorative motifs shows that many are borrowed or shared between the countries of the Gulf and the Arab world. Do you have any favourites in terms of dress or anecdotes that illustrate most precisely the messages contained in costume/dress?

AR: I have not studied dress extensively in other countries of the Arab world but of course notice interesting details when I see them. Omani dress for example had several variations with important identifiers, including styles that distinguished seacoast dwellers from those living in the interior as well as ethnic differences of the residents. Of course, the mask [or Burqa] worn by women in the UAE and along the coast is unique to the region but few realize women cut it in a way to enhance their better features. One time I was sitting with some village women in Muzandam and they kept pulling out different sized masks for me to try on until they found the right one that covered most of my face. “There you look more beautiful!” they said.

People in Arabia have strong feelings about how dress shows respect for others. A proverb says “Eat what you want but dress to respect others.” Men cover their heads out of respect, and both sexes wear neat, presentable dress that respects those they are visiting. One day I was in Al-Ain going with hospital workers to vaccinate children in surrounding villages. It was hot and I was wearing Pakistani shirwaal khamis that I thought would be comfortable. When I arrived in al-Ain I found the vaccine campaign had been cancelled. But since we were near the home of a woman the staff knew, they suggested we visit her instead. She greeted us warmly and sat me next to her but after a few minutes, she beckoned for me to follow her into her bedroom. There she opened a wardrobe filled with dresses and stacks of material and brought out one dress after another for me to put on. I did but they all came to just below my knees and she discarded them as being too short. Finally, she handed me a length of cloth and told me to have it made up into a dress like hers “that was more befitting a person of my status.” She had seen my Pakistani outfit as something a servant would wear.

One book I refer to often is a book on “Aesthetics in the UAE” written by Aida Kanafani that is the most complete description of customs in the Gulf I know. Her book has a picture of the exact dress I had made up out of the material my generous hostess had given me.

SK: Finally, turning to men: In the UAE, there are different ways of tying the guthra, according to region and according to age. In your Egyptian research, you focus on their head scarfs and beards .. noting that men have fewer visual identifiers. Why do you think this is? Is this to do with religion, issues of gender, power or perhaps simply time?

AR: Men focus on communicating different values from women. What I find most interesting in the Gulf is what you describe about the men’s headscarves and the identities and meanings they convey. There are geographical identifiers in the way men’s headscarves are wrapped. For example, in Omen, the headscarves are wrapped as turbans and the cloth itself often comes from India. In the rest of the Arabian Peninsula, men wear the kafiyya or ghrutra headcloth. A Saudi can be recognized by the two tiny folds in the kafiyya at the centre of his forehead, and Gulf Arabs by the cords and tassels that hang from their agal headbands. If the headcloth looks “jauntily” positioned it is often a Jordanian.

The similarities between the Gulf kandara and the Saudi thobe suggest a sense of common tribal origin and interest. At the same time, the UAE men’s kandara with its elegant perfume flap distinguishes them from Saudis. Overall, of course, the use of “national dress” in the UAE sets local citizens apart from foreign workers. It is not appreciated when foreigners don local dress in an act of cultural appropriation. This is contrary to the case in Pakistan where foreigners are encouraged to wear the local dress.

One other point to show how details spread: the Saudis were first to introduce “international” details—pockets, cuffs and mandarin collars–into their traditional thobes while keeping the main shape of the gown. Egyptian workers in Saudi Arabia returning to their villages often took Saudi thobes back with them to Egypt to show their greater wealth and sophistication compared to the local peasants with their voluminous gallabiyas.

All this goes to show the wealth of meaning to be found in dress, and how important it is for a group like the Zay Initiative to be taking on this commitment in the Arab world.

Thank you so much Dr Rugh, for your valuable insights.

Further reading

Reveal and Conceal – Dress in Contemporary Egypt by Dr Andrea Rugh

Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion Vol 1

The cloth of Egypt – All about Assiut by Dawn Devine-Davina and Alisha Westerfield

About the Author

Sophie Kazan fell in love with Islamic Art and decoration after visiting the Louvre in Paris and she enjoys exploring the materiality of objects and cultural paradigms. She studied Art and Archaeology of Asia and Africa (BA Hons), completing her Masters in History of Art and Archaeology (University of Oxford) and researched how tradition and modernity are represented in contemporary art by Emiratis (School of Museum Studies, University of Leicester). Sophie enjoyed talking to Andrea Rugh about life in the UAE, Egypt and Saudi Arabia and how many cultural beliefs and philosophies are translated into clothing and traditional dress. Learn more about Sophie’s work on her website and Instagram profile.

*All images in this post are sourced from the slides of our Dialogues on the Art of Arab Fashion webinar conversation with Dr Andrea Rugh which took place on 2 March 2021. If you missed this fascinating experience, you can get access to the full back catalogue of webinar episodes by becoming a Friend of the Zay.

Latest Comments

POST YOUR OPINIONUnderstanding Cultures Through Regional Dress - Sophie Kazan PhD

May 6, 2021[…] Continue reading: Understanding Cultures… […]

Multiple Lives – An interview with Shahira Mehrez - The Zay Initiative

June 6, 2021[…] Read Sophie’s interview with Dr Andrea Rugh here. […]

Reveal and Conceal - Dress in Contemporary Egypt - The Zay Initiative

September 10, 2021[…] An interview with Dr Angela Rugh by our guest contributor Dr Sophie Kazan, can be read here. […]