Imaginarium Postcard Women – Part 2

A Very Small Piece of Clothing

In this

short series of blog posts I am exploring the representations and misrepresentations of women, their bodies, and adornments in 19

th-century/early 20th-century colonial postcards from the Middle East and North Africa through the distorting lenses of Orientalism, colonialism, the male gaze, and 19th-century ‘ethnography’.

I will be looking at oppositions and juxtapositions like east vs west, traditional-as-static vs modern-as-progressive, and ideas of costume versus clothing. Through my work as an artist, art historian, and writer working with this problematic archive since 2018, I have been trying to disentangle some of these concepts used to frame Postcard Women and thinking about how we can be more aware of how the frameworks and language we choose continue to create difference and misunderstanding even as we attempt to decolonise the lens and this archive.

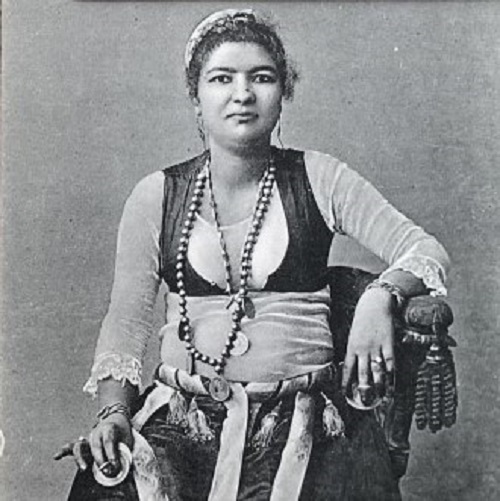

Here I am thinking through these entanglements using the example and multiple textures of a small, intricate, beautiful piece of adornment. The smallest of things that women wear has the potential to create big waves out there in the world of ‘men’, power and the gaze.

A small garment

You could perhaps call this piece of clothing a kind of waistcoat,

bodice

Bodice: (English: body), or bodices the plural form of body, it is the close-fitting garment meant to cover the body above the waist or the torso. However, it was not until the 17th century that the term became synonymous to women’s undergarment. , or jacket. It can be found shown very often on the bodies of the Postcard Women from these regions. In Algeria, it is called the

frimla; the very closely related

ghlila also often appears on postcards.

I am sure each region has its own terminology and history for these garments and not being an expert in dress and heritage I constantly need to find articles and books by historians of dress. I am amazed every time by the variety, multiplicity, richness, and complexity of the cultural meanings and practical uses of garments and adornment. In our so-called modern era, we still use this language of adornment to embody and signify our identity, pleasure and place in society in profound ways that we are not fully aware of.

The body language of adornment

So-called traditional societies understood this better. The body language of adornment played a vital part in how women’s and men’s bodies and selves were constructed and embedded into society's norms and expectations. It allowed them to express their being in creative and practical ways.

Adornments were more entwined in ancestry, often handed down over generations. The processes of crafting, embroidering, weaving, silversmithing, dyeing and marking the skin, and so forth, were gestures inscribed with movements of the body of both maker and wearer, soaked in cultural understanding of purpose, meaning, and making.

But let's not think that creativity, ingenuity, development, and fluidity of meanings, both personal and societal, were not also a very important part of how adornments evolved and adapted. Invisible languages were understood unspoken, as they emanated from bodies moving around homes and streets where scents, perfumes, the sounds of jewellery, rituals, and practical daily life merged.

The acts of making ourselves special (‘making special’ is a term used by Ellen Dissanayake in her book Homo Aestheticus) through bodily adornment and arranging our environment, is part of a process both physiological and social, that activates us and our bodies, facilitates our understanding and transformation - our becoming.

Societies may often aim to carve out and control women’s bodies and activities but women are not passive carriers of societal codes, they have long been in control of shaping their world, adapting, transgressing, and creating their own identities.

A living visual language

I recently found a fascinating dissertation online by Morgan T. Snoap, called

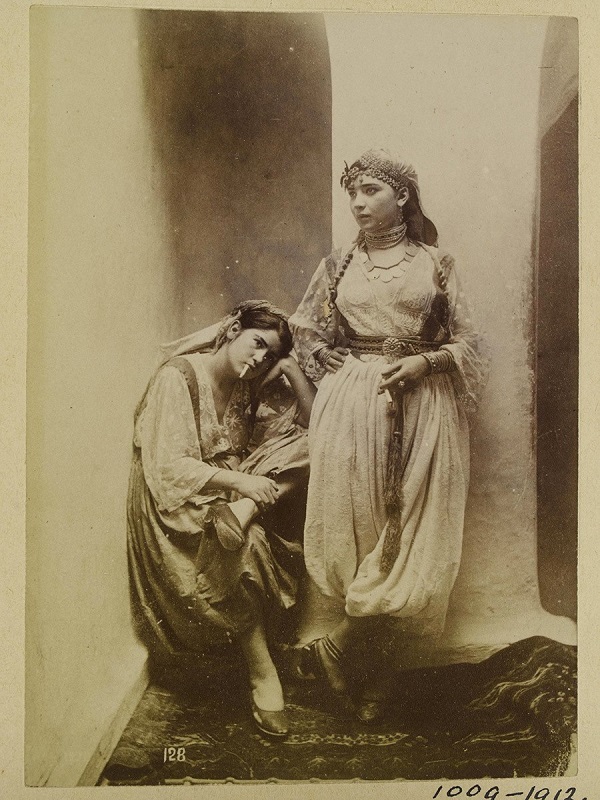

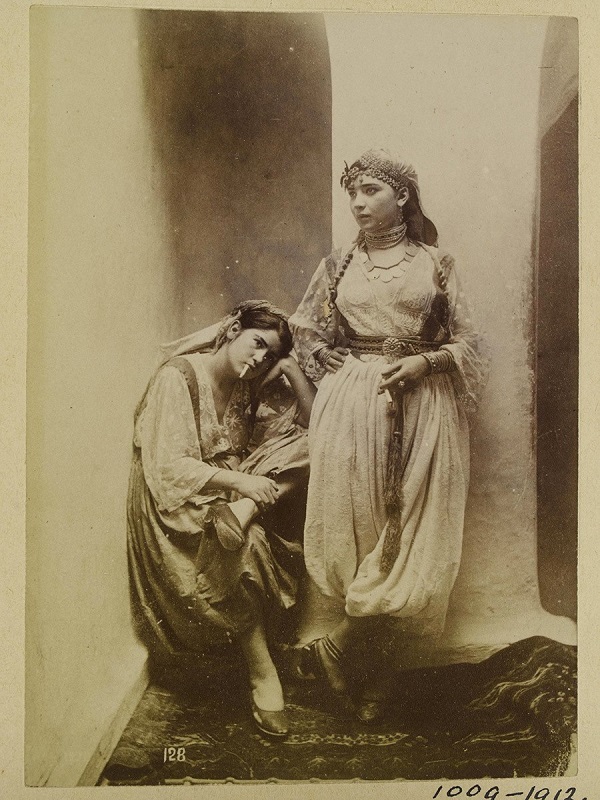

Algerian Women’s Waistcoats - The Ghlila and Frimla: Readjusting The Lens on the Early French Colonial Era in Algeria (1830 -1870). I quickly learned that the ‘waistcoats’ were a kind of living visual language worn on the body. They allowed practical household work to be carried out through the function of supporting the chest and holding long sleeves of blouses out of the way, held in place under the waistcoat at the back.

At the same time the changing designs, wide choice and status of the types of fabrics, silks, cotton, the levels of the richness of embroidery, use of the evil eye symbolism in designs, kinds of linings, and so forth, revealed how women negotiated social status and made their own distinct and informed choices in a world of changing fashion. Nothing about these garments was static, unchanging, or had anything to do with the erotics of languishing on an

Oriental

Oriental: (Latin and Late Middle English Adjective: orientalis – From Orient; from Latin (noun): oriri – to rise; and oriors – East), anything of an Eastern origin in relationship to Europe – Asia. The word was first used in the context of territorialization between the late 3rd and early 4th Century CE. sofa, not doing much, smiling and smoking, as colonial and Orientalist writing, photography, and painting would have us believe.

A woman’s world

In the domestic space of home and family, women worked alongside their servants and socialised at the markets, bathhouse, and mosque exchanging worries, and knowledge about cooking, child-rearing, and healing. Women had their own language of signs, movements, gestures and looks to negotiate their world without interference from the men, as discussed by Marina Lazreg.

Even though these garments would never have been visible in public, hidden beneath an outer veil or cloak, and certainly not ever visible to any foreign men, that does not mean they were not an important part of women’s everyday economies of living, of being active agents through dress choices for their work at home and outside.

These women made practical, creative, fashion, and status-conscious decisions and led busy lives doing what was hugely important within society and community, as it was in Europe, managing the smooth running of the home. Educating and bringing up children, who are very often missing from postcard imagery, except where another colonial ‘ethnographic’ narrative of diminishment and difference is in operation.

The Orientalist gaze

The erotic, sensual, and unrealistic fantasies of the Orientalist gaze blended with the increasingly appropriative colonial and imperial gaze. Photography, writing, and painting were used as tools to recreate women as a single ‘type’ - erotic, exotic, lazy, sedentary, primitive, corrupt, uneducated, lacking in agency, or recreated as ethnographic types utterly different from European women, and needing an organising and civilising force.

Increasingly these modes conflated women’s bodies, coded as sensual, erotic purposeless ‘props’, with these waistcoats that were written about by European men as a kind of hyper-sexualised lingerie. These practical and beautiful works of contemporary craftsmanship passed on through Andalusian and Ottoman artisans to local artisans and handed down between women, became denuded trifles.

In early writings by textile historians who were visiting the MENA region in the days before the colonial project became increasingly aggressive, toxic and moralising, there is a certain ‘ethnographic’ distance in precise detailing of the materials, decorations, craftsmanship and uses of pieces like the

frimla as Snoap explains. Later, the visual and textual commentary on clothing became inseparable from a moralistic, reductive commentary on the women’s bodies, how much nude flesh was being revealed by the clothing, suggesting her primitive appetites, immorality and marking her as racially different from a European woman.

Clothing and woman became one, ‘props’ in a colonial and Orientalist agenda. So in working with the imagery of women on postcards we are working against reductive stereotypical depictions of an entire way of life. And it is important to say that this notion of the detached neutral European ‘observer’ who merely ethnographically documented everything they possibly could in the early days of colonial expeditions and expansion is problematic.

Even today the Western European derived mode of ‘objective’ observation, recording and documentation is a kind of surveillance and control of cultural meaning and we have to be careful about how we use it regarding cultural heritage which has both stable and unstable, fluid, and ever-changing dimensions.

Documenting heritage

Multiplicity is a word that matters in my work with colonial postcards of women, and in my art practice. The hegemony of the singular narrative endangers the voices of women. Historians of dress do the vital job of documenting and discussing the textiles, craftsmanship, provenance, lineage and cultural meanings of these adornments - textiles and jewellery. The importance of documenting these pieces and their cultural histories is a way to reclaim legacies back from colonial narratives that have stripped all depth of meaning by turning everything into ‘props’ and corrosive simplistic signs for the colonial

Oriental

Oriental: (Latin and Late Middle English Adjective: orientalis – From Orient; from Latin (noun): oriri – to rise; and oriors – East), anything of an Eastern origin in relationship to Europe – Asia. The word was first used in the context of territorialization between the late 3rd and early 4th Century CE. woman.

We need to be wary of creating yet another hegemony where fixed static documentation leaves out the multiplicity, variety, and variability of oral histories. Women’s personal narratives and experiences may not always fit larger frameworks of the historical document, they blur the boundaries and lines drawn by academic writing and may become marginalised by mainstream ‘canons’.

Often it is the words, language, and framing of discourse adopted from European discourse that can imprison pieces of adornment within structures and ways of thinking, This does not allow for other ways in which things take on significance within a specific lived culture through the varied individual bodies, tongues, and generations of wearing, usage and reimagining. Through rituals, songs, lives lived, and cross-cultural sharing over time. Oral histories have often been looked down upon as opposed to ‘scientific’ ‘factual’ ‘rigorous’ ways of fixing knowledge. We need to always bring in the fluidity and disruptive nature of the personal histories handed down over generations of women.

The bigger picture

It is important to point out how some of these postcards look, well, quite harmless, even seeming to indicate a genuine image or genuine interest in that woman, person, or her dress. The problem is always the larger frame. The bigger picture and context that such images were taken within. And what is left out. And how each postcard is a fragment and part of the history of the colonial project.

It is also vital to be aware that the colonial and imperial project was not equal everywhere. Each place has its own ‘flavour’ of postcards. Algeria was subjected to particularly violent and horrendous occupation by the French, a different colonial experience from being a ‘protectorate’ like Tunisia and Morocco.

The postcards from the protectorates are not any less problematic, but it matters to be aware of specifics and particulars, precise contexts and circumstances of the different representations. I have also included an image of postcards from various regions in my collection all wearing types of ‘waistcoats’. You can observe the variety of ways of posing women, gazing, fully or partially/barely dressed, leaning, lounging, smiling, and smoking. Some are coded as romantic or exotic, sensual or erotic and others as ‘ethnographic’ types, supposedly one nameless woman standing in for all of her ‘kind’.

*Images attached are from my personal postcard archive and images from the V&A archive taken by Claude-Joseph Portier in the 1860s

References

- The Eloquence of Silence: Algerian Women in Question by Marina Lazreg

- Ornamental Feeling: The Body of Life and Death in the work of Daisy Patton by Salma Ahmad Caller from the book Broken Time Machines: Daisy Patton by Minerva Projects

- Remaking Women: Feminism and Modernity in the Middle East edited by Lila Abu-Lughod

- Rethinking Orientalism: Women, Travel and the Ottoman Harem by Reina Lewis

- Ethnopornography: Sexuality, Colonialism, and Archival Knowledge ed. Pete Sigal, Zeb Tortorici & Neil L. Whitehead

- Images of Women: The Portrayal of Women in Photography of the Middle East 1860 - 1950 by Sarah Graham-Brown

- Rethinking Decoration: Pleasure & Ideology in the Visual Arts by David Brett

- Homo Aestheticus by Ellen Dissanayake

About the Author

Salma Ahmad Caller was born in Iraq to an Egyptian father and a British mother and grew up in Nigeria and Saudi Arabia. She now lives in the UK. An artist, art historian and writer who is a hybrid of cultures and faiths she is drawn to hybrid and ornamental forms, and to how the body expresses itself in the mind to create an embodied ‘image’. She is particularly interested in cross-cultural and in mixed-race identities, experiences and embodiment. Her work embraces collage, drawing, watercolour, photography, projection, installation and sound. Salma also writes art theory, poetry and creative non-fiction, with a theoretical background in research on the meanings of ornament in non-Western cultures through frameworks of anthropology of art and cognitive science, with the aim of contributing to the decolonisation of art history and theory and breaking down boundaries and categories that support hegemonic colonial and patriarchal formations.

With a Masters in art history and art theory, a background in medicine and pharmacology, and several years of teaching cross-cultural ways of seeing via non-Western artefacts at Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, she now works as an independent artist and teacher.

*A recording of

the webinar where Salma Ahmad Caller discussed this project with Dr Reem el Mutwalli, can be accessed through

Friends of The Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period.