Brid Beeler moved to Saudi Arabia in 1989 and stayed for a decade. Her career then led her to live and work in Yemen and Oman and work for some of the world’s top travel companies. She currently heads

Brid Beeler Travel Ltd and travels in and out of the region regularly. This is the second in a two-part series where Brid shares her personal experience and knowledge of the history and fate of Yemeni silversmiths and their craft. Read the first article here.

Bab Al Yemen entrance to the old city of Sanaa

Yemen opens to the world

For most westerners, Yemen was a little-known entity until well into the second half of the twentieth century as it had been since the

Sabaean era and the rule of

Bilquis, the Queen of Sheba. Aden and South Yemen had been a British Protectorate before becoming a communist state supported by the Soviet Union in 1967. North Yemen had been ruled by the Zaydi Imams for over a thousand years until 1962 when a revolution brought about the fall of Imam rule and the establishment of a democratic government. As embassies and some international NGOs began to trickle into the new democratic state, outsiders had their first opportunity to visit this land. Western contacts and travel to Yemen increased significantly in 1990 when North and South Yemen united under a government based in Sana’a.

Travellers fortunate enough to visit Yemen in the earlier days found a country awash with silver jewellery. From the mountains of the Yemeni highlands to

Shibam in the

Hadhramawt, each region had distinctive craftsmanship and its own silversmiths who were sought out for their workmanship. The Yemenis also knew how to work stones and resin. Amber in all its shades of golden to orange and red,

coral

Coral: (Greek: korallion, probably from Hebrew: goral – small pebbles), is a pale to medium shade of pink with orange or peach undertones, resembling the colour of certain species of coral. in shades of white, pink, red and black,

turquoise

Turquoise: (French: turquois – present day Türkiye; Synonyms: firuze, pheroza), is a naturally occurring opaque mineral mined in abundance in Khorasan province of Iran and has been used for making dye for centuries. The term is a derivative of the French word for the country Türkiye once called Turkey. , a matrix style (that came from Saudi Arabia), carnelian, red glass, and agate in a myriad of shades were worked, mostly in a cabochon style.

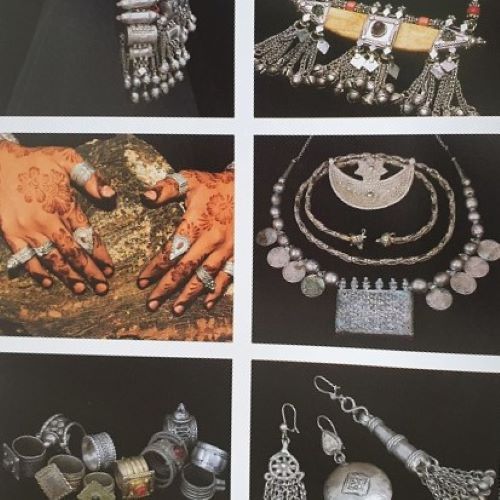

Yemeni Jewish silver selection

My first introduction to Yemeni silver

My first serious encounter with Yemeni silver was an assault on the senses. I travelled to Yemen on a three-week-long road trip after the Gulf War of 1991. We had driven south from Riyadh and, as the border post at Najran was closed, we headed out into the Empty Quarter (

Ar Rub Al Khali) towards

Sharoura, navigating by compass and with some rather dated topographic maps. Our first night in Yemen was in the walled town of

Al Buga a northern desert outpost with border officials and customs checks. The trip was to be a life-defining moment, with my love affair with Yemeni silver jewellery beginning as we travelled all over Northern Yemen over three weeks. The craftsmanship and the array of amber, carnelian, agate,

coral

Coral: (Greek: korallion, probably from Hebrew: goral – small pebbles), is a pale to medium shade of pink with orange or peach undertones, resembling the colour of certain species of coral., red glass, and freshwater pearls were all available as part of stunningly beautiful necklaces, rings, and bracelets. The larger, more elaborate pieces were no longer making their way across borders into Saudi Arabia where a lucrative expatriate market existed.

Yemeni silver in Saudi Arabia

When western expatriates began to work in Saudi Arabia, many started collecting traditional silver jewellery found in the souqs, with little knowledge of what they were buying. Heather Coyler Ross came to the rescue in the 1980s with two extremely well-researched books on Bedouin jewellery of the Arabian Peninsula, primarily covering Saudi Arabia. While they provided a fascinating insight into the jewellery, they did not address the jewellery from Yemen. This is despite many of the silversmiths in the Kingdom being from Yemen. At that time, Yemenis enjoyed a privileged status in the Kingdom. They could cross the border without visas, own property, and establish businesses with ease.

Khamis Meshet Souq in Asir in Saudi Arabia

Silver and politics

Sadly, this changed with the onset of the first Gulf War when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in August 1990. Yemenis were forced to leave Saudi Arabia in retaliation for their government’s political decision over the Iraqi invasion. Previously, the souqs of the Asir and Jeddah were full of Yemeni traditional jewellery, less so in Riyadh, and expatriates naturally sought out these pieces. After the Gulf War, however, it became evident quite quickly that the jewellery was becoming scarce, and Yemen was becoming isolated with access to markets in the west no longer easily accessible.

In response, and within a decade, influential Yemeni businessmen with the support of the Yemeni government began a charm offensive promoting Yemeni culture abroad in some of the capitals of Europe and Washington DC. This was a time of pride for Yemen as the Yemeni ‘flowermen’ performed with their traditional garlands of flowers and herbs while dressed in their traditional woven

mowaz (sarong or

futa

Futa: (Classical Persian), a cloth used either as an apron or a bath wrapper ).

Yemen being the birthplace of coffee,

Kohlan coffee from the outskirts of Sana’a was brought to Washington DC and sold in the Smithsonian Institution’s marketplace, along with frankincense and myrrh, colourful Yemeni woven baskets, and flat woven

Kilim

Kilim: (Persian: Gilīm or galīm from Akkadian or Aramaic; Synonym: Plas), a traditional weaving technique with possible Central Asian origins. It involves tightly interlacing weft

Weft: one of the two basic components used in weaving that transforms thread or yarns into a piece of fabric. It is the crosswise thread on a loom that is passed over and under the warp threads. and warp

Warp: One of the two basic components used in weaving which transforms thread or yarns to a piece of fabric. The warp is the set of yarns stretched longitudinally in place on a loom before the weft

Weft: one of the two basic components used in weaving that transforms thread or yarns into a piece of fabric. It is the crosswise thread on a loom that is passed over and under the warp threads. is introduced during the weaving process. threads to create flat-woven geometric patterned rug and tapestry

Tapestry: wall hanging or other large piece of fabric that is woven in coloured weft

Weft: one of the two basic components used in weaving that transforms thread or yarns into a piece of fabric. It is the crosswise thread on a loom that is passed over and under the warp threads. threads or embroidered with a decorative design. Typically made of wool, but they can also be made of other materials such as silk, linen, or cotton. Often used to decorate homes, churches, and other buildings. fabrics in vibrant colours. It is widely popular across Central Asia, Iran, and Türkiye. style carpets. Befitting its cultural importance, Yemeni silver was prominently displayed for sale at these joint government-sponsored events and every piece of jewellery was sold by the Yemeni silversmiths to an appreciative American audience. Unfortunately, before this promotion of the cultural riches and arts of Yemen could achieve much success, terrorism became a part of our vocabulary and the tide shifted once more against Yemen and these opportunities to travel abroad to support government events became increasingly difficult.

Selection of jewellery in the main marketplace in old Sanaa

Loss of heritage through conflict

China has had a long influence in Yemen through various cultural, technical, and economic development projects. Yemeni jewellers were able to travel to China for three to six months to participate in trade shows where they could sell their jewellery. But most Yemeni jewellers would only take what could easily be sold and began adapting designs to the latest fashion pieces seen in glossy western magazines. The internet has made this easier with images on social media easily available for all. Even in the war-torn Yemen of today, with its frequent electrical outages, the internet continues to be a major influence in households with generators.

But as the current war-driven economic collapse puts pressure on families, those who know the value of their jewellery understandably put their family’s wellbeing first and may be left with no choice but to melt down valuable pieces for cash or, if there is a way to get them to the west, sell them on the international market. As is to be expected, there has been an increase in the illegal trade of antique Yemeni artefacts from the

Sabaean era popping up from time to time for sale in the west. The sad reality is that many countries face a loss of heritage as a result of conflict and Yemen is not the first nor will it be the last country to do so.

Ben Zion David. Yemeni silversmith in old Jaffa

The fate of Jewish silversmiths

As to what happened to all the Yemeni Jews who travelled to Israel under operation Magic Carpet (see the first article in this series) - most remained in Israel, some went to the United States, and a few returned to Yemen.

My first encounter with Yemeni Jews was in the highlands around

Hajjah in 1991. In subsequent years, I lived and worked in Yemen on two occasions over almost six years and I would see small numbers from time to time, dressed as a Yemeni in traditional

mowaz, riding motorbikes, chewing qat, and otherwise being part of Yemeni society. I left Yemen during Christmas week 2011 as the country was already in conflict, just before the tribes converged upon the capital of Sana’a blocking every access in and out of the city. I do not know the fate of the remaining Yemeni Jews, but during the thousand years of Zaydi Imam rule, Yemeni Jews were protected. Given the many tragedies of the recent conflict, one cannot help but be concerned.

While Muslim silversmiths continue to make traditional silver jewellery for the local market, the market for such items is much reduced, as is the number of artisans practising their craft. Consumer tastes have changed as well, with a younger audience increasingly wanting modern items rather than the older styles favoured by previous generations. Yemenis are resilient, but they face unsurmountable challenges. Given the state of Yemen’s economy, how long can these skilled artisans continue practising their craft? A valuable heritage is at risk, and it will be a devastating loss for all of us if markets cannot be found for their exquisite traditional jewellery.

About the author

In 2015, Brid Beeler managed the

Smithsonian Institution’s Sackler Gallery tour in Saudi Arabia, Oman and Qatar, which followed Saudi Arabia’s internationally acclaimed

Roads of Arabia exhibition. Brid facilitated the

History Channel’s Yemen documentary

Digging for the Truth – The Real Queen of Sheba. She also participated in the multi-level cultural project involving the Smithsonian and the Yemen and US governments that resulted in the publication of

Caravan Kingdoms: Yemen and the Ancient Incense Trade. With Crossing the Line Films, she facilitated logistics and key components for their award-winning documentary on the annual Qashqai migration in Iran, which was aired by

National Geographic under the title

Last Chance Journeys: Iran. Brid also consulted on a UNICEF, World Food Program project advocating for girls’ education in Yemen.

She has presented papers on eco-tourism in the region and was one of only a handful of women selected to speak at the first International Conference on Eco-Tourism in Saudi Arabia. Her other speaking engagements have included

The Ethnic Silver Jewelry of the Arabian Peninsula at the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin Castle. She currently contributes monthly to

aramcoexpats.com. Her collecting, which began in the souqs of Riyadh before extending to Yemen, Oman, and further afield, focuses on old silver jewellery, semi-precious stones, beadwork, and textiles from the Arabian Peninsula

*Copyright to all images belongs to Brid Beeler unless otherwise indicated. Reproduced here with permission. Feature image from

Marjorie Ransom's book Silver Treasures from the land of Sheba.

Read the first article in this series here.Read more articles by Brid Beeler

- Bukhnug

Bukhnug: (Arabic: khanaq: to choke, pl. bakhānq, bakhānk), a form of veil (Niqāb), serves as a (hijāb) used by young girls and women, to cover the head, neck, and upper body, the sides of which are pinned, or sewn, under the chin. Colloquially, the letter (qāf) is pronounced (ga). – A Chance Encounter

- ‘Usabah: A Delicate Silver Circlet

- Libat Mazamir – A Yemeni Wedding Necklace