Brid Beeler moved to Saudi Arabia in 1989 and stayed for a decade. Her career then led her to live and work in Yemen and Oman and work for some of the world’s top travel companies. She currently heads

Brid Beeler Travel Ltd and travels in and out of the region regularly. This is the first in a two-part series where Brid shares her personal experience and knowledge of the history and fate of Yemeni silversmiths and their craft.

Bab Al Yemen entrance to the old city of Sanaa

Yemeni silver jewellery and social-economic changes

Most of the jewellery sold in the Middle East today is from India and Southeast Asia, produced in quantity and sold at affordable prices. Jewellery making is, after all, a business that must consider the cost of materials, marketing, payroll, shipping, etc., and it makes financial sense to keep costs low and sales high to maximize profits. The traditional, handcrafted silver jewellery long associated with the region is seen less and less.

Jewellery is art pieces to be worn and, much like a painting proudly displayed in your home, it has both an intrinsic value and makes a personal statement, defining who you are, your tastes and often your place in society. While we have become a more global, inclusive society, I believe there is a renewed interest in tradition emerging from a desire to have something authentic with traceability to a specific time and culture.

If so, why do we see a decline in silversmiths working in traditional ways? What has happened to the pieces made by the old Jewish silversmiths, like the families of Bowsane, Bedehe and Mansouri who once lived and worked in Yemen?

The answers lie in several fundamental socio-economic changes, chief of which have been the decline of the Bedouin lifestyle, the mass migration of the Jewish population in the region to Israel in the years immediately following World War II, and the availability of new materials.

Bedouin tented camp, near Al Ula, Saudi Arabia

The changing role of artisans in Bedouin culture

Nomadic people like the Bedouins of the Arabian Peninsula and the Levant herded their animals in search of fresh pasture and water. They did not roam the deserts aimlessly, they moved their flocks and households within a delineated area, and this was defined by what they could carry, be it on the back of camels or worn on the body or sewn into the lining or pockets of women’s clothing as they walked. Jewellery was a form of wealth like a savings account and that wealth had to be portable.

The Bedouins never practised artisan work themselves, rather they sought out the silversmiths from towns. The silversmiths were the craftsmen and had a secondary status within the tribal structure. In a large tribe, the Bedouins would have their own artisan class solely working for them. Smaller tribes would use craftsmen found in suqs. Today, in Yemen, the existence of the artisan class still exists among Muslim silversmiths.

Currently, there are only about forty million nomadic people left in the world and the Bedouin lifestyle has been in decline over the past 50-plus years. With the advent of motorised transport, the pickup truck replaced camels as the ship of the desert. Bedouins no longer needed to move their animals on foot by crossing vast stretches of the desert over three to six weeks, they now could do so by loading them into a truck and taking them to a wintering area where they are fed alfalfa by workers who are employed to do so. Owning camels today is more a hobby than a necessity.

With this decline in the Bedouin lifestyle has come a similar decline in using silver as a portable means of storing wealth and the need to employ artisans in its manufacture.

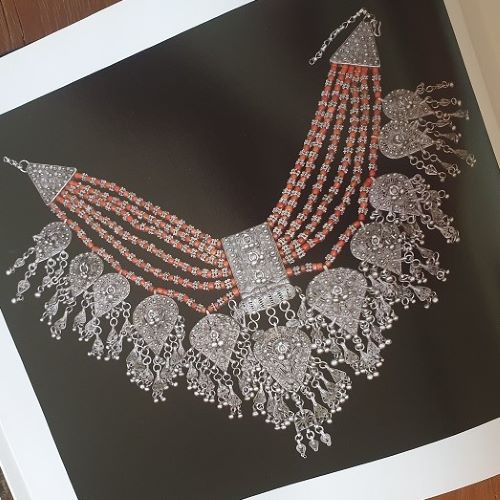

Yemeni Jewish silver selection

The changing role of Jewish silversmiths

Traditionally, most of the silversmiths in the region were Jewish. With the Jewish migration from the area in 1949 and 1950 under the rein of Imam Ahmed, Operation Magic Carpet involved many flights of Yemeni Jews to the Promised Land. 49,000 Yemeni Jews were airlifted on British and American planes to Israel, along with 2,000 Jews from Saudi Arabia and smaller numbers from Djibouti and Eritrea. This initially resulted in the decline of exquisite workmanship as much of the skill on the peninsula was lost as the Jewish silversmiths were master craftsmen. Before they departed from Yemen, Imam Ahmed instructed the Jewish silversmiths to train Muslims in the craft. Today, most Muslim silversmiths who remain are in their fifties and older. Silversmithing remains in the family lineage from father to son within the artisan class. Marjorie Ransom has spent a lifetime collecting Yemeni silver and is the author of the definitive book,

Silver Treasures from the Land of Sheba (AUC Press, 2014). She is currently working on a second book on Yemeni Muslim silversmiths and how they are continuing in the craft today.

The decline of the artisan class

Sadly, most of the Yemeni Jews that immigrated to Israel became second-class citizens in the new state. Some became disillusioned and returned to Yemen but others remained in Israel and at least one such silversmith has continued practising his ancestral craft. In 2012, I was in Israel managing and guiding a Stanford University Alumni graduate group. While in Old Jaffa, we walked through the main central open thoroughfare with alleyways leading off in many directions. Stepping into one of these narrow alleyways, on the left was

Yemenite Art, and the silversmith Ben Zion David bent over his work. While his gallery was awash with stunningly beautiful pieces which I immediately recognised as Yemeni Jewish workmanship, he was working in the back, in the same rudimentary way seen today in the workshops of silversmiths in Yemeni souqs. I was delighted to see the workmanship of his Yemeni ancestors alive and well in his exquisite designs. He was happy to meet someone familiar with the practice of his craft in Yemen, who had lived in Sana’a and who had collected many of the old Jewish pieces of Bowsane, Bedehe and Mansouri. He wanted to know more about his ancestral homeland and invited me to return but, unfortunately, it was not feasible at the time.

Gold and artisans from the sub-continent

Against the decline of the Bedouin lifestyle and the immigration of Jewish silversmiths, the other changes contributing to the decline of silversmithing in the region are more subtle. Yemeni expatriates working in the Gulf countries began purchasing and bringing home to family members gold jewellery from India and elsewhere, with the preference being for 21- and 24-karat gold over the lesser 18-karat gold. Oil wealth in the Gulf provided an opportunity for Arabs to own gold shops and hire jewellers from India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh to make jewellery on their home turf. Gold has been mined historically throughout the Arabian Peninsula and this was a newfound opportunity. Yemeni silversmiths found work in the souqs in Gulf countries, working in both gold and silver shops.

Unfashionable silver

Silver was becoming passe and old-fashioned. While larger pieces continued to be popular in Yemen, in the Gulf countries the desire was to have these traditional chunky designs rendered in gold as opposed to silver. At one point in Yemen’s history, many

Hadrami pieces would have had gold wash applied over the silver content. This is a different process from dipping in gold. Today these large gold items worn at weddings are more often rented than owned because of the exorbitant costs associated with the many kilos of gold necessary for the occasion.

Marriage had always necessitated a dowry of jewellery to be provided by the groom’s family to secure the bride’s future financially. Jewellery was her security blanket in the event of divorce. It was hers and hers alone. This tradition is still intact today, although household items like washing machines and other modern-day appliances have become part of the dowry too, reflecting a more affluent lifestyle. Additionally, jewellery was not always passed down from mother to daughter. Sometimes it was sold upon her death, back into the marketplace and was melted down to create a new silver piece or purchased by a collector.

About the author

In 2015, Brid Beeler managed the

Smithsonian Institution’s Sackler Gallery tour in Saudi Arabia, Oman and Qatar, which followed Saudi Arabia’s internationally acclaimed

Roads of Arabia exhibition. Brid facilitated the

History Channel’s Yemen documentary

Digging for the Truth – The Real Queen of Sheba. She also participated in the multi-level cultural project involving the Smithsonian and the Yemen and US governments that resulted in the publication of

Caravan Kingdoms: Yemen and the Ancient Incense Trade. With Crossing the Line Films, she facilitated logistics and key components for their award-winning documentary on the annual Qashqai migration in Iran, which was aired by

National Geographic under the title

Last Chance Journeys: Iran. Brid also consulted on a UNICEF, World Food Program project advocating for girls’ education in Yemen.

She has presented papers on eco-tourism in the region and was one of only a handful of women selected to speak at the first International Conference on Eco-Tourism in Saudi Arabia. Her other speaking engagements have included

The Ethnic Silver Jewelry of the Arabian Peninsula at the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin Castle. She currently contributes monthly to

aramcoexpats.com. Her collecting, which began in the souqs of Riyadh before extending to Yemen, Oman, and further afield, focuses on old silver jewellery, semi-precious stones, beadwork, and textiles from the Arabian Peninsula

*Copyright to all images belongs to Brid Beeler unless otherwise indicated. Reproduced here with permission. Feature image from Marjorie Ransom's book

Silver Treasures from the land of Sheba.

The second article in this series will examine changes in contemporary Yemen as they impact traditional silver jewellery.Read more articles by Brid Beeler

- Bukhnug

Bukhnug: (Arabic: khanaq: to choke, pl. bakhānq, bakhānk), a form of veil (Niqāb), serves as a (hijāb) used by young girls and women, to cover the head, neck, and upper body, the sides of which are pinned, or sewn, under the chin. Colloquially, the letter (qāf) is pronounced (ga). – A Chance Encounter

- ‘Usabah: A Delicate Silver Circlet

- Libat Mazamir – A Yemeni Wedding Necklace