Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

) tunic with frontal neckline opening. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. , mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ) loose, short or long sleeved, shirt like (qamisQamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences./dishdashah) neckline.", which is a triangular-shaped piece of fabric that descends from the neckline of the dishdashah Dishdāshah: (Persian: deshan: newly worn, synonyms: ghandurah Ghandūrah: (Arabic, pl. qanādīr, synonyms: qandurah Qandūrah: (Arabic, pl. qanādīr, synonyms: ghandurah, darā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, qaftan, mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ), a loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamis) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. , darā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, qaftan Qafṭān: (Persian: khaftān, Pl. qafāṭin, synonyms: ghandurah, qandurah Qandūrah: (Arabic, pl. qanādīr, synonyms: ghandurah, darā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, qaftan, mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ), a loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamis) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. , drā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, kandurah, mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ) loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamisQamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

) tunic with frontal neckline opening. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. , mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ), a loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamisQamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences., qandurah Qandūrah: (Arabic, pl. qanādīr, synonyms: ghandurah, darā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, qaftan, mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ), a loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamis) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. , dra’ah, jalabah Jallābah: (Arabic jilbāb pl. jalābīb, jalābāt, synonyms: ghandurah, qandurah Qandūrah: (Arabic, pl. qanādīr, synonyms: ghandurah, darā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, qaftan, mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ), a loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamis) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. ,, dra’ah, jallābīya, qaftan Qafṭān: (Persian: khaftān, Pl. qafāṭin, synonyms: ghandurah, qandurah Qandūrah: (Arabic, pl. qanādīr, synonyms: ghandurah, darā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, qaftan, mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ), a loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamis) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. , drā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, kandurah, mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ) loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamisQamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

) tunic with frontal neckline opening. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. , kandūrah, mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ), loose, short or long sleeved, qamisQamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

-like tunic that covers the body, with frontal neckline opening. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. , jallabiya, qaftan Qafṭān: (Persian: khaftān, Pl. qafāṭin, synonyms: ghandurah, qandurah Qandūrah: (Arabic, pl. qanādīr, synonyms: ghandurah, darā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, qaftan, mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ), a loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamis) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. , drā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, kandurah, mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ) loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamisQamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

) tunic with frontal neckline opening. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. , kandurah Kandūrah: (Arabic: qandūrah, pl. kanādīr, synonyms: ghandurah, qandurah Qandūrah: (Arabic, pl. qanādīr, synonyms: ghandurah, darā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, qaftan, mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ), a loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamis) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. , dra’ah, dishdāshah, jallābīyah, jalābah, jillābīyah, qaftan Qafṭān: (Persian: khaftān, Pl. qafāṭin, synonyms: ghandurah, qandurah Qandūrah: (Arabic, pl. qanādīr, synonyms: ghandurah, darā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, qaftan, mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ), a loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamis) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. , drā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, kandurah, mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ) loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamisQamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

) tunic with frontal neckline opening. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. , mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ) loose, short or long sleeved, shirt like (qamisQamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences., mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. , or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ) from the verb ‘to wear’, literally meaning ‘something that is newly worn’, loose, short or long sleeved, qamisQamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

-like tunic that covers the body, with frontal neckline opening. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. . We will cover the farukhah Farūkhah (Arabic: farkh: chick, synonym: farkhah) colloquially in UAE & Oman, it refers to a braided tassel hung on men’s tunic (kandurah Kandūrah: (Arabic: qandūrah, pl. kanādīr, synonyms: ghandurah, qandurah Qandūrah: (Arabic, pl. qanādīr, synonyms: ghandurah, darā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, qaftan, mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ), a loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamis) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. , dra’ah, dishdāshah, jallābīyah, jalābah, jillābīyah, qaftan Qafṭān: (Persian: khaftān, Pl. qafāṭin, synonyms: ghandurah, qandurah Qandūrah: (Arabic, pl. qanādīr, synonyms: ghandurah, darā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, qaftan, mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ), a loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamis) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. , drā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, kandurah, mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ) loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamisQamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

) tunic with frontal neckline opening. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. , mqta’, thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ) loose, short or long sleeved, shirt like (qamisQamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

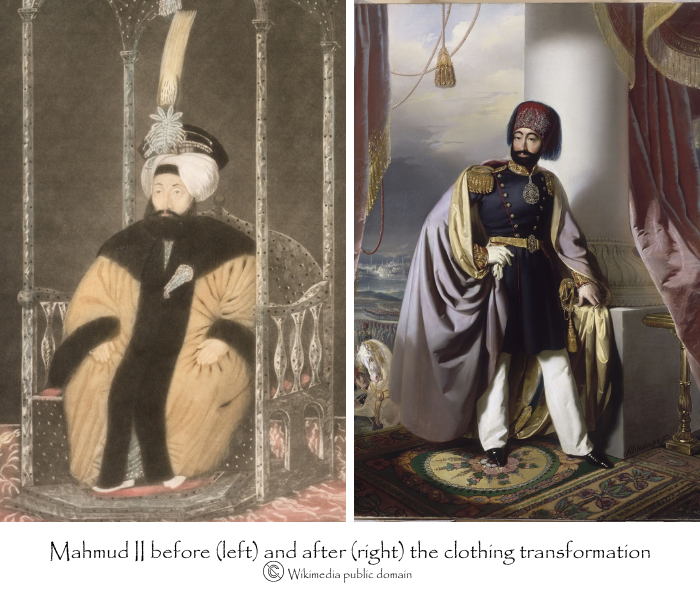

) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences./dishdashah) neckline. in the future. In this blog, we are exploring the tarbush which adorned the heads of many Arab men for over a century.

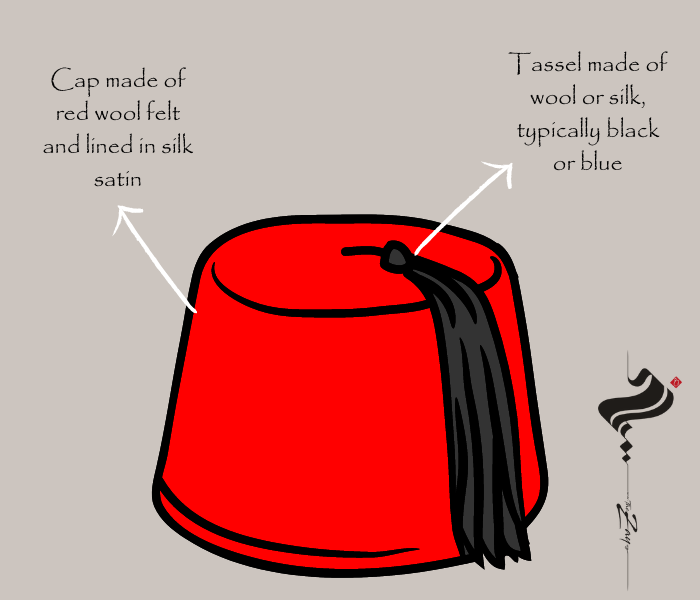

Fez: (Ottoman Turkish: fes boyası - madder

Madder: (Latin: Rubia tinctorum – Eurasian herb), rose madder, common madder or dyer's madder is a vegetable dye made from the roots of a perennial plant belonging to the bedstraw and coffee family. It has been used extensively as a vegetable red dye across the globe from India to England. Ṭarbūsh: (Turkish: terpos – turban; from Persian serposh – headdress; Synonym: fez), a type of traditional skull cap with a high crown. With a possible Mediterranean origin, this head wear gained popularity in the late Ottoman period and became the forerunner of other similar caps with slight variations.

Ṭarbūsh: (Turkish: terpos – turban; from Persian serposh – headdress; Synonym: fez), a type of traditional skull cap with a high crown. With a possible Mediterranean origin, this head wear gained popularity in the late Ottoman period and became the forerunner of other similar caps with slight variations.

, tarbooch, tarboosh, tarbush, chachia, chechia, fezFez: (Ottoman Turkish: fes boyası - madder

Madder: (Latin: Rubia tinctorum – Eurasian herb), rose madder, common madder or dyer's madder is a vegetable dye made from the roots of a perennial plant belonging to the bedstraw and coffee family. It has been used extensively as a vegetable red dye across the globe from India to England. Ṭarbūsh: (Turkish: terpos – turban; from Persian serposh – headdress; Synonym: fez), a type of traditional skull cap with a high crown. With a possible Mediterranean origin, this head wear gained popularity in the late Ottoman period and became the forerunner of other similar caps with slight variations.

Fez: (Ottoman Turkish: fes boyası - madder

Madder: (Latin: Rubia tinctorum – Eurasian herb), rose madder, common madder or dyer's madder is a vegetable dye made from the roots of a perennial plant belonging to the bedstraw and coffee family. It has been used extensively as a vegetable red dye across the globe from India to England. Ṭarbūsh: (Turkish: terpos – turban; from Persian serposh – headdress; Synonym: fez), a type of traditional skull cap with a high crown. With a possible Mediterranean origin, this head wear gained popularity in the late Ottoman period and became the forerunner of other similar caps with slight variations.

Fez: (Ottoman Turkish: fes boyası - madder

Madder: (Latin: Rubia tinctorum – Eurasian herb), rose madder, common madder or dyer's madder is a vegetable dye made from the roots of a perennial plant belonging to the bedstraw and coffee family. It has been used extensively as a vegetable red dye across the globe from India to England. Ṭarbūsh: (Turkish: terpos – turban; from Persian serposh – headdress; Synonym: fez), a type of traditional skull cap with a high crown. With a possible Mediterranean origin, this head wear gained popularity in the late Ottoman period and became the forerunner of other similar caps with slight variations.

Fez: (Ottoman Turkish: fes boyası - madder

Madder: (Latin: Rubia tinctorum – Eurasian herb), rose madder, common madder or dyer's madder is a vegetable dye made from the roots of a perennial plant belonging to the bedstraw and coffee family. It has been used extensively as a vegetable red dye across the globe from India to England. Ṭarbūsh: (Turkish: terpos – turban; from Persian serposh – headdress; Synonym: fez), a type of traditional skull cap with a high crown. With a possible Mediterranean origin, this head wear gained popularity in the late Ottoman period and became the forerunner of other similar caps with slight variations.

Fez: (Ottoman Turkish: fes boyası - madder

Madder: (Latin: Rubia tinctorum – Eurasian herb), rose madder, common madder or dyer's madder is a vegetable dye made from the roots of a perennial plant belonging to the bedstraw and coffee family. It has been used extensively as a vegetable red dye across the globe from India to England. Ṭarbūsh: (Turkish: terpos – turban; from Persian serposh – headdress; Synonym: fez), a type of traditional skull cap with a high crown. With a possible Mediterranean origin, this head wear gained popularity in the late Ottoman period and became the forerunner of other similar caps with slight variations.

Fez: (Ottoman Turkish: fes boyası - madder

Madder: (Latin: Rubia tinctorum – Eurasian herb), rose madder, common madder or dyer's madder is a vegetable dye made from the roots of a perennial plant belonging to the bedstraw and coffee family. It has been used extensively as a vegetable red dye across the globe from India to England. Ṭarbūsh: (Turkish: terpos – turban; from Persian serposh – headdress; Synonym: fez), a type of traditional skull cap with a high crown. With a possible Mediterranean origin, this head wear gained popularity in the late Ottoman period and became the forerunner of other similar caps with slight variations.