This is the second post in our series on veiling in the UAE. Find the first post here. In this post, we will look at facemasks in more detail.

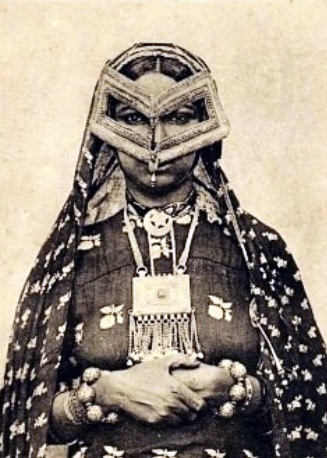

Face masks look different in various parts of the Muslim world. Usually, it covers the nose, chin and sometimes the neck and is often attached to other forms of headcover. The urban style mask used in the UAE, Bahrain, Qatar and Oman is known as the burghu (UAE)or batulah Baṭūlah: (Arabic), face mask covering the chin or slightly more, with varying eye cut-outs. Used by women in Bahrain, Emirates, Qatar, Oman, and southern Iran. More widely known in the Arab world as (burqa’) where the letter [qaf] in many Arab regions is pronounced [gah]. (Bahrain, Qatar and Oman) and is different from the Bedouin-style mask known as al-maghrun or al-niqab Niqāb: (Arabic: face cover), cloth face veil or mask with two cutouts, holes or openings for the eyes. or al-baghrah which is made of a softer fabric.

In the UAE the most common term for a facemask is al-burghu or al-batulah Baṭūlah: (Arabic), face mask covering the chin or slightly more, with varying eye cut-outs. Used by women in Bahrain, Emirates, Qatar, Oman, and southern Iran. More widely known in the Arab world as (burqa’) where the letter [qaf] in many Arab regions is pronounced [gah]., yet other terms like al-maghrun, al-niqab Niqāb: (Arabic: face cover), cloth face veil or mask with two cutouts, holes or openings for the eyes., al-wasusah and al-qina is sometimes used and may cause confusion. Some people use the same name for different styles of mask and some people use different names to refer to the same style of mask!

Burqu in Arabic means ‘that which conceals a woman’s face’ and is most commonly used in the UAE as al-burghu.

Batula is a word more commonly used in Oman, Bahrain, and Qatar and has two possible origins:

Ba ta la meaning ‘to make something distinct from other things’ possibly referring to the mask’s function of distinguishing the eyes from the rest of the face, or

Batola, a Persian word from Sanskrit origin referring to woven fabric covers, screens or partitions.

Historically the term burghu referred to a form of hijab

Hijāb: (Arabic: cover, amulet or protection; Synonym: bukhnuq, khimār), a form of traditional coif for women and young girls covering the head, neck but could also be longer. Also refers to any garment with a triangular amulet motif by Egyptians.

In upper-class Turkey, it was made of silk and was known as yashmak

Yashmak: (Old Turkic yaş – to hide), a traditional face veil commonly used by women in the Turkmen and other Turkic society. It has different variants depending upon its geographical locations ranging from a thick veil made of horse to a thin lace veil covering the face with slits for the eyes. . In Egypt, middle-class women wore white muslin

Muslin: (Arabic: Mosul – A city in Iraq, or French: Mousse – Foam; Synonym: Mulmul; Melmel), a fine variety of plain-woven cotton unique to the Gangetic Delta – Ganges, Padma, and Meghna rivers. The term is either a derivative of Mosul, where it exchanged hands or "mousse" due to its lightweight and fluffy texture. , commoners wore thick black crepe

Crepe: (Latin: crispus; Old French: crespe – curled or frizzed), is a lightweight, crinkled fabric with a pebbled texture woven from a hand spun untreated or ‘in the gum’ silk yarn.

Today, the term burgha refers to a different style of face cover most commonly found in the UAE, Qatar, parts of Oman, the island of Faylaka in Kuwait and in some areas on the southern coast of Iran. The exact origin of the burghu is unclear but scholars have two theories.

1. It originated in Persia and came to the Arabian Gulf via trade between the Gulf communities and neighbouring Bandar Tahiri (Siraf) an important commercial centre in the Gulf and the largest port in Iran. It declined after the 10th century.

2. It is based on the Sanskrit origins of the word batulah Baṭūlah: (Arabic), face mask covering the chin or slightly more, with varying eye cut-outs. Used by women in Bahrain, Emirates, Qatar, Oman, and southern Iran. More widely known in the Arab world as (burqa’) where the letter [qaf] in many Arab regions is pronounced [gah].. After the decline of Siraf the Baluchi people of Southern Iran began migrating across the gulf to Oman. They spoke a mixture of Persian and Urdu Indian and established themselves as a dominant domestic and manual labour force. They became followers of the Sultan of Oman and in the process introduced some of their customs and traditions to their masters, the native Arab population. Through the Baluchi’s interaction with the slave class, it is possible that slave women were the first to adopt the burghu/batulah Baṭūlah: (Arabic), face mask covering the chin or slightly more, with varying eye cut-outs. Used by women in Bahrain, Emirates, Qatar, Oman, and southern Iran. More widely known in the Arab world as (burqa’) where the letter [qaf] in many Arab regions is pronounced [gah]. in an attempt to raise their social status. The shiny nature of the mask emulated the shine of gold in lieu of more expensive gold jewellery.

The burghu is made from percale cotton imported from India. Known locally as shit kham or kharjat nil Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye., the fabric looks like leather, is dark brown or black, thin and smooth. It is indigo Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. stained which gives it a golden sheen and consequently the mask stains the wearer’s face in humid weather. The fabric is sold in single, stiff, folded sheet measuring 1 x 2 meters, enough to make 22 masks. The burghu is lined with gauze Gauze: (English), very fine wire mesh transparent fabric of silk, linen, or cotton. material called lazigh, meaning ‘to stick’ as the gauze Gauze: (English), very fine wire mesh transparent fabric of silk, linen, or cotton. is glued to the back of the indigo Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. stained cotton to help prevent the indigo Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. from staining the wearer’s face.

The burghu is tied around the head with a braided string called a ghitan, meaning lace. It is made of red or green cotton or silver thread. For the cotton ghitan, the right string is 30-40 cm and the left string is 18-22 cm. For silver ghitan, the right string is a longer 65-75 cm.

To fasten the mask, the long string is passed through the loop formed by the shorter string and pulled tight, fixing it to the head with the excess string hanging down the back of the head.

Khat

Khaṭ: (Arabic: line, pl. khtūt). al-hijab

Hijāb: (Arabic: cover, amulet or protection; Synonym: bukhnuq, khimār), a form of traditional coif for women and young girls covering the head, neck but could also be longer. Also refers to any garment with a triangular amulet motif by Egyptians.

Al-ghardhah – eye openings – is usually almond shape varying in size. Young, unmarried women usually wear smaller, stylised versions with larger eye openings to enhance their best features. The elderly, the widowed or brides-to-be wear larger masks with smaller openings to signal their strict adherence to custom or to preserve their modesty.

Al-khudud – meaning cheeks – refers to the area covering the cheekbones. It can vary in shape and coverage depending on the wearer’s age and personal preference.

Al-ghdhab – meaning to prune or cut - is the protruding stiff ridge covering the nose made from a wooden splint obtained from a palm frond. This provides rigidity and an axis for proportion and symmetry.

Al-masatir – a thin, supple support inserted on each side of the mask to help stiffen the edges and give the whole mask a defined shape.

Ghardhat al-tham – the lower part of the mask covering the jaw curve and mouth. The length of this piece varies according to age. Older women wear longer forms of the burghu that covers the neck area while younger women tend to wear shorter versions that barely covers the mouth.

For special occasions such as weddings and in more affluent families, the burghu was decorated with round, domed coin-like gold disks called huruf placed in a row along the top of the mask covering the eyebrows. This was probably an improvisation on the Bedouin burghu which was often decorated with silver adornments completely covering the forehead.

Another type of gold ornament, called mishakhis were sometimes sewn on, fifteen or so to a side above the huruf at the side edge of the burgha.

The Qatari batulah Baṭūlah: (Arabic), face mask covering the chin or slightly more, with varying eye cut-outs. Used by women in Bahrain, Emirates, Qatar, Oman, and southern Iran. More widely known in the Arab world as (burqa’) where the letter [qaf] in many Arab regions is pronounced [gah]. tends to have an overall almond shape with rectangular eye slits and the cheek/mouth section extending to just above the lip line allowing a slight trace of the lower lip to show. Qatari and Baluchi women tied their batulah Baṭūlah: (Arabic), face mask covering the chin or slightly more, with varying eye cut-outs. Used by women in Bahrain, Emirates, Qatar, Oman, and southern Iran. More widely known in the Arab world as (burqa’) where the letter [qaf] in many Arab regions is pronounced [gah]. strings over their shaylah Shaylah: (Colloquial Gulf Arabic), a length of fabric used as shawl, head cover or veil. Also known as (wigāyah) or (milfa’), generally made from sheer fabrics such as tulle (tūr), cotton gauze (wasmah Wasmah: (Arabic: woad), is derived from the woad herb (wasmah) used to dye the cotton gauze black. It is mainly used for headcovers or veils and overgarments in most of the Arab gulf region.) (nidwah) or (Nīl), or silk chiffon (sarī)..

The UAE burghu is more delicate and refined with larger eye openings that have a curvier shape. UAE women tie the burghu directly over their hair with their shaylah Shaylah: (Colloquial Gulf Arabic), a length of fabric used as shawl, head cover or veil. Also known as (wigāyah) or (milfa’), generally made from sheer fabrics such as tulle (tūr), cotton gauze (wasmah Wasmah: (Arabic: woad), is derived from the woad herb (wasmah) used to dye the cotton gauze black. It is mainly used for headcovers or veils and overgarments in most of the Arab gulf region.) (nidwah) or (Nīl), or silk chiffon (sarī). covering the strings.

Originally every woman made her own burghu in a process known as gharh. Some women became recognised for their skill and were commissioned by other women to make theirs. A worn-out burghu is discarded and never recycled although some of the decorations might be reused.

There is no standard pattern as each women hand sews her own and cut it according to her own preference and facial features. To start with, the general shape is drawn or traced from an existing one. It is then cut, and the edges are folded and stitched.

Another method is to start with a rectangular piece of cloth folded and stitched down the middle forming a pleat. The two eye slits are then cut and their edges neatly stitched. This stitching requires steady, dry hands and is regarded as a great talent. Damp, sweaty, untrained hands cause the indigo Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. colour to run, spoiling the fabric, and weak, unsteady hands produce uneven, frail and damaged edges.

Traditionally, the burghu was worn as soon as a girl began to show signs of puberty. It was worn out of modesty rather than religion, both at home and out in the public. Other than during prayer time or hajj, when it was replaced by a prayer shawl Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. , it was only removed during intimate times between a husband and wife, when sleeping or on rare occasions such as doctor’s visits.

To eat or drink, a woman lifted the lower end of the burghu by placing the index finger of the left hand under the stiff central ridge and pushing it up, resting the left thumb next to her mouth under her lower lip. Once the food is placed in her mouth with her right hand, the burghu is dropped back in position and she chews with the burghu completely concealing her mouth.

When the burghu is not worn it is folded in the middle, wrapped in tissue paper and kept in a box or drawer.

These days, customs have changed, and many younger women don’t wear the burghu at all and some only wear it at official or special ceremonies and events. Yet, the habit of covering the mouth still remain, and many women will involuntary cover their mouths with their hands or the hanging side of their hair veil when they are in the company of other people.

The burghu is viewed by older UAE men and women as a form of adornment or embellishment, and an aid to enhance good features and hide less appealing features.

“The outline of the mask harmonises the lines of the nose, softens the contour of the nostrils, shortens a long chin, elongates a flat chin, plays down accentuated jaws and conceals a larger mouth. Moreover, a mask shields against bad breath, hides bad teeth and conceals various skin blemishes such as wrinkles, pimples, moles and scars.” A.S. Kanafani

Some people also believe the burghu encourages communication as it requires the listener to pay special attention to the eyes of the speaker, reading body language and overall forces one to pay more attention while communicating.

The burghu is viewed by some as a way to enhance romance between a husband and wife. By hiding her face from him and from everybody else during the day, it becomes an erogenous zone once she reveals herself to him in private.

The older generation of UAE nationals still perceives the burghu as a symbol of national identity.

During the 1970s girls were encouraged to attend a school where the burghu was not part of the uniform. Girls and young women only started wearing it once they got married, some as young as thirteen.

Exposure to the outside world during this period introduced new styles inspired by world fashion. The eye openings became larger, revealing more of the cheeks and showing off the wearer’s modern make-up.

The introduction of machine stitching and the emergence of women specialised in making these items changed the culture from women making their own masks to having them made by designers and tailors.

From the 1980s onward as women entered tertiary education and the workforce, the marriage age went up and women who never grew accustomed to wearing the burghu during their school years now abandoned the tradition completely. These days only the older women still adhere to this tradition.

Shaykh Zayed bin Sultan al Nahyan, founding father and ruler of the UAE insisted that the women in his family wear traditional costume, including the burghu. This insistence is now credited for the survival of the national UAE dress, an important part of the UAE national identity, even in the 21st century.