Salma: I don’t think any colonising imperialist project can be seen in a positive light. A violent takeover is a violent takeover. Exploitation is exploitation. Theft is theft. Killing is killing. Misrepresentation is a misrepresentation. If X runs you over with their car and then pays for your children to go to school I don’t think this would be seen as a positive outcome. For history books to then happily write about how wonderful X educated your children in the way they wanted them to be educated, whilst leaving out the part where they left you for dead, well that wouldn’t be an outcome anyone should be content with ….

This might seem like a funny example but that is what we are talking about. The things people like to list as ‘benefits’ of imperialism/colonialism could have been achieved in many other ways not requiring the violent subjugation and exploitation of others’ lands, stripping of resources and cultures, and the creation of deadly divisions and boundaries between peoples. It always is the more privileged classes and groups that were able to ‘benefit’ from Western European Imperial institutions. So what one group might call a benefit is simply another mechanism of subjugation and exclusion for many other groups.

Also, important questions arise regarding imperial systems, be they transport, education, trade, farming, language, art, or health systems. What systemic prejudices and erasures are ingrained within these systems that are still being perpetuated today? The structural systems set in place by imperial colonial industrial complexes have structural biases so deeply entangled with the so-called positives of these systems, that it will take years to work all those out. Structural systems also work to keep those in power in their places. Systems prioritise certain kinds of people, certain languages, and so forth and thereby exclude others. Those ‘types’ and ‘categories’ that draw lines and boundaries, developed in the 18th and 19th centuries, are to be found underlying all western ‘canonical’ modes of thinking, knowledge structures and institutions, in sciences, art history, engineering, medicine, etc. thereby excluding all other non-western modes of being, seeing, making, and thinking. So dismantling goes hand in hand with recovery, reexamination of past traditions, cultural heritages, and lost or marginalised ways of being as we move forward.

We cannot in all consciousness always talk about colonialism without also reflecting deeply on how our own subjective positions/privileges implicate us, and without asking how we are dealing with these complex issues regarding new forms of colonialism, racism, and marginalisation of minorities ongoing in the Arab and wider world, and we discuss this a lot on our group forum as well. But this doesn’t and shouldn’t let the West off the hook - one wrong doesn’t cancel out another, and I see this in a lot of troubling social media posts, where the idea that if one country has its own issues and problems that means it is in no position to complain about colonialism or racism from the West, which was enacted on a grand and epic scale. But equally, we have to take ownership of what we can and must address. What racial hierarchies are alive and well in the Arab world? What strife and misery do workers brought over to build new empires suffer right now? It’s always a complicated discussion of course. And more than just pointing fingers, constructive ways forward need to be found. But the ugly face of racial stereotyping on colonial postcards in turn shows us the ugly face of racism and prejudice at home. Many leaders in the Arab world, Asia, and Africa have taken extreme advantage of colonial systems to wield power over their people and carry out their own forms of despotism as they have in the West.

We all stand to benefit by asking questions of ourselves. We also cannot proceed by ignoring or trying to erase that past or pretend that it wasn’t so bad because they gave us schools and built bridges - they did that for themselves, not for the people of those countries, but to perpetuate systems of control, to facilitate trade, to gain more power. But complicating the binary narrative of dominated vs subjugated is a powerful decolonising tool. In so many ways peoples of colonised lands have always resisted and found ways to reappropriate Western modes of knowledge or use traditional forms to intervene, creating and evolving their bodies and identities, even as they lived under oppressors. And as I mentioned in the webinar, the Zar ritual is a fascinating example - of how women of lower social classes drew on the heritage of black and marginalised peoples to create a subversive power network of their own running under the radar of the state, to deal with women’s difficulties, psychological problems, depression, domestic violence, and deal with oppressors from their own communities as well as foreign invaders. Rather than simply shun this practice as ‘backward’ and ‘primitive’ we could understand it as a form of networking and creating relationships/survival based on different modes of being, where imagination, the understanding of the body, performance, music, healing, and sharing are centre stage.

Another example is the Amazigh women and how they are reclaiming their heritage, emancipation and voices through jewellery, textiles and tattoos which serve as a visible form of cultural heritage, as political and social resistance. Amazigh culture, folk traditions, music, poetry, rituals, adornment, are transmitted chiefly by the women across generations and women traditionally had a very open, emancipated, public role in their society and community, yet in recent decades colonial misrepresentations combined with conservative religious and patriarchal forces have been fiercely oppressing them, silencing them, and keeping them from participating in the public sphere. They have been fighting back using the potent embodied and visual presence of body adornments and associated rituals to increase their voices and visibility which is now being embraced more widely in Morocco.

Salma: I don’t think any colonising imperialist project can be seen in a positive light. A violent takeover is a violent takeover. Exploitation is exploitation. Theft is theft. Killing is killing. Misrepresentation is a misrepresentation. If X runs you over with their car and then pays for your children to go to school I don’t think this would be seen as a positive outcome. For history books to then happily write about how wonderful X educated your children in the way they wanted them to be educated, whilst leaving out the part where they left you for dead, well that wouldn’t be an outcome anyone should be content with ….

This might seem like a funny example but that is what we are talking about. The things people like to list as ‘benefits’ of imperialism/colonialism could have been achieved in many other ways not requiring the violent subjugation and exploitation of others’ lands, stripping of resources and cultures, and the creation of deadly divisions and boundaries between peoples. It always is the more privileged classes and groups that were able to ‘benefit’ from Western European Imperial institutions. So what one group might call a benefit is simply another mechanism of subjugation and exclusion for many other groups.

Also, important questions arise regarding imperial systems, be they transport, education, trade, farming, language, art, or health systems. What systemic prejudices and erasures are ingrained within these systems that are still being perpetuated today? The structural systems set in place by imperial colonial industrial complexes have structural biases so deeply entangled with the so-called positives of these systems, that it will take years to work all those out. Structural systems also work to keep those in power in their places. Systems prioritise certain kinds of people, certain languages, and so forth and thereby exclude others. Those ‘types’ and ‘categories’ that draw lines and boundaries, developed in the 18th and 19th centuries, are to be found underlying all western ‘canonical’ modes of thinking, knowledge structures and institutions, in sciences, art history, engineering, medicine, etc. thereby excluding all other non-western modes of being, seeing, making, and thinking. So dismantling goes hand in hand with recovery, reexamination of past traditions, cultural heritages, and lost or marginalised ways of being as we move forward.

We cannot in all consciousness always talk about colonialism without also reflecting deeply on how our own subjective positions/privileges implicate us, and without asking how we are dealing with these complex issues regarding new forms of colonialism, racism, and marginalisation of minorities ongoing in the Arab and wider world, and we discuss this a lot on our group forum as well. But this doesn’t and shouldn’t let the West off the hook - one wrong doesn’t cancel out another, and I see this in a lot of troubling social media posts, where the idea that if one country has its own issues and problems that means it is in no position to complain about colonialism or racism from the West, which was enacted on a grand and epic scale. But equally, we have to take ownership of what we can and must address. What racial hierarchies are alive and well in the Arab world? What strife and misery do workers brought over to build new empires suffer right now? It’s always a complicated discussion of course. And more than just pointing fingers, constructive ways forward need to be found. But the ugly face of racial stereotyping on colonial postcards in turn shows us the ugly face of racism and prejudice at home. Many leaders in the Arab world, Asia, and Africa have taken extreme advantage of colonial systems to wield power over their people and carry out their own forms of despotism as they have in the West.

We all stand to benefit by asking questions of ourselves. We also cannot proceed by ignoring or trying to erase that past or pretend that it wasn’t so bad because they gave us schools and built bridges - they did that for themselves, not for the people of those countries, but to perpetuate systems of control, to facilitate trade, to gain more power. But complicating the binary narrative of dominated vs subjugated is a powerful decolonising tool. In so many ways peoples of colonised lands have always resisted and found ways to reappropriate Western modes of knowledge or use traditional forms to intervene, creating and evolving their bodies and identities, even as they lived under oppressors. And as I mentioned in the webinar, the Zar ritual is a fascinating example - of how women of lower social classes drew on the heritage of black and marginalised peoples to create a subversive power network of their own running under the radar of the state, to deal with women’s difficulties, psychological problems, depression, domestic violence, and deal with oppressors from their own communities as well as foreign invaders. Rather than simply shun this practice as ‘backward’ and ‘primitive’ we could understand it as a form of networking and creating relationships/survival based on different modes of being, where imagination, the understanding of the body, performance, music, healing, and sharing are centre stage.

Another example is the Amazigh women and how they are reclaiming their heritage, emancipation and voices through jewellery, textiles and tattoos which serve as a visible form of cultural heritage, as political and social resistance. Amazigh culture, folk traditions, music, poetry, rituals, adornment, are transmitted chiefly by the women across generations and women traditionally had a very open, emancipated, public role in their society and community, yet in recent decades colonial misrepresentations combined with conservative religious and patriarchal forces have been fiercely oppressing them, silencing them, and keeping them from participating in the public sphere. They have been fighting back using the potent embodied and visual presence of body adornments and associated rituals to increase their voices and visibility which is now being embraced more widely in Morocco.

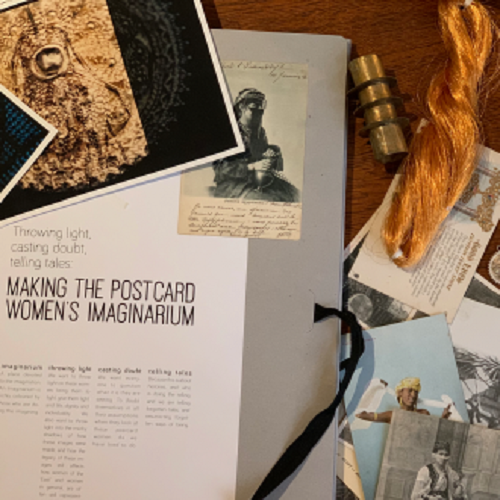

With the Imaginarium postcard project - our full title is Making The Postcard Women’s Imaginarium, we aimed to create alternative Imaginariums, visual regimes and narratives that not only counteract toxic and false misrepresentations/racial stereotyping of women from the MENA region, but that also create positive creative new visual forms that bring in many other layers of histories, generate more questions and open out the dialogue. By reinstating marginalised silenced voices of women - and they have not just been silenced from the colonial period, we are drawing attention more widely to issues for women today from the region and globally as well. In creating art together with dialogue about colonial postcards, Imaginarium artists and researchers are drawing in what they understand, have experienced, and are bringing in their heritage as handed down from their mothers, great grandmothers/families. Oral histories are essential to the process of decolonising the archive and canons.

And so it is empowering and inspiring to hear the colonial ‘props’ now singing and speaking through women today, reframing both the marginalised bodies silenced on postcards but also reframing women’s cultural heritage, experiences and stories in our age. Each piece of jewellery or cloth or object in the postcards can be thought of as a song. As soon as you start to sing the song, you being to remember the movements, gestures, stories, and voices that went along with it. Women’s positions and status in so-often labelled ‘traditional’ societies are never what they seem. Women have always been powerful actors even as they have always fought against violence and oppression on multiple fronts.

National identity can be a sensitive topic, but rather than seeking to ‘own’ the narratives of meanings surrounding material cultural heritage, we see the commonalities and how each community and place has developed and used something in similar and different ways, as a means to solidify bonds rather than draw boundaries. That is what we hope can be healing and positive about our project. As a group of six artist-researchers with backgrounds from Egypt, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Morocco, we bring out what is shared in histories as well as specifics of locality and experience. And Jewish, Christian, black Arabs, and other peoples and ethnicities and their stories are an invaluable part of the vital and full story of cultural heritage in the MENA region. The multi-ethnic multi-cultural diversity behind each piece reveals to us we are not one isolated ‘nation’ of a singular identity, that we have a silsila or silver chain that binds us to our ancestors and so many others. The brand of identity and nationalism that does not accept the porousness of our borders, often falsely constructed to create inequality and divisions, is one that perpetuates colonial and imperial damage. We should be using our heritage to build webs of connections and relationships not to draw lines and build walls in imperial style.

There are many people of formerly colonised countries who are doing that, who have adapted and altered imperial modes to create something different, something better, something less invasive, and who are creative, resilient, positive forces in helping keep marginalised or endangered cultures, heritage, and languages alive and developing new ways of being, sharing resources and living. Those who are refusing old imperial ways of subjugation, control, possession, and domination.

Going back to this question of ‘did Imperialism and colonialism have any benefits’ the very big problem with this is that it fixes us all in a binary narrative constantly concerned about an idea of Western progress as the ONLY one - where there is the underlying assumption that the ‘progress’ brought by colonisers was the singular way forward for humanity to the exclusion of a whole globe full of possible other ways of living a good life as human beings - a binary narrative that disguises and obliterates other possible ways that ‘progress’ could have happened and disguises the violence of the means.

If we keep the narrative rigged to the damaging binary where the West symbolises an idea about the progress that was always ‘meant to be’ and all other ways of seeing and being in the world are backward and traditional then we are at a standstill. There is often an assumption that ‘development’ and ‘progress’ and ‘civilisation’ could only have happened in the way that they did. Embedded in these three terms is the idea that the future is always better than the past without pause for thought. With the violent erasure of other/others’ ways of being that have been labelled ‘backward traditions’ we must ask what have we lost or forgotten? Imperial cultures have more than enough of their own backward traditions but these are also masked in these discussions. This comparative binary always leaves us exhausted, trapped in a single either/or dichotomy. We have to dig ourselves out of this.

The imagery of the colonial postcard women illustrates this problem very well - by showing a certain representation that excludes not only the violence done but that also conceals ALL other possible modes of living and being. There are many ways forward for humanity without relying on a system predicated on racial hierarchies and violent dominance. Forms of representations like the postcard imagery and how we represent issues then dictate the questions we can ask, the language we can use and even what we can think. We need to create new modes that allow us to think beyond this structure and start asking ourselves different questions.

I used to teach at Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. Visitors and students were always obsessed with the Treatment of Dead Enemies display case in the museum. A gory and grotesque display of how ‘indigenous’ peoples treated their enemies. Yet people were always dumbfounded when I asked them how they think Europeans treated and treat their dead enemies? Are modern warfare practices of killing via drone bombing more ‘civilised’ just because it involves advanced ‘technology’? Do they think Western armies carefully respectfully bury their dead enemies?

With the Imaginarium postcard project - our full title is Making The Postcard Women’s Imaginarium, we aimed to create alternative Imaginariums, visual regimes and narratives that not only counteract toxic and false misrepresentations/racial stereotyping of women from the MENA region, but that also create positive creative new visual forms that bring in many other layers of histories, generate more questions and open out the dialogue. By reinstating marginalised silenced voices of women - and they have not just been silenced from the colonial period, we are drawing attention more widely to issues for women today from the region and globally as well. In creating art together with dialogue about colonial postcards, Imaginarium artists and researchers are drawing in what they understand, have experienced, and are bringing in their heritage as handed down from their mothers, great grandmothers/families. Oral histories are essential to the process of decolonising the archive and canons.

And so it is empowering and inspiring to hear the colonial ‘props’ now singing and speaking through women today, reframing both the marginalised bodies silenced on postcards but also reframing women’s cultural heritage, experiences and stories in our age. Each piece of jewellery or cloth or object in the postcards can be thought of as a song. As soon as you start to sing the song, you being to remember the movements, gestures, stories, and voices that went along with it. Women’s positions and status in so-often labelled ‘traditional’ societies are never what they seem. Women have always been powerful actors even as they have always fought against violence and oppression on multiple fronts.

National identity can be a sensitive topic, but rather than seeking to ‘own’ the narratives of meanings surrounding material cultural heritage, we see the commonalities and how each community and place has developed and used something in similar and different ways, as a means to solidify bonds rather than draw boundaries. That is what we hope can be healing and positive about our project. As a group of six artist-researchers with backgrounds from Egypt, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Morocco, we bring out what is shared in histories as well as specifics of locality and experience. And Jewish, Christian, black Arabs, and other peoples and ethnicities and their stories are an invaluable part of the vital and full story of cultural heritage in the MENA region. The multi-ethnic multi-cultural diversity behind each piece reveals to us we are not one isolated ‘nation’ of a singular identity, that we have a silsila or silver chain that binds us to our ancestors and so many others. The brand of identity and nationalism that does not accept the porousness of our borders, often falsely constructed to create inequality and divisions, is one that perpetuates colonial and imperial damage. We should be using our heritage to build webs of connections and relationships not to draw lines and build walls in imperial style.

There are many people of formerly colonised countries who are doing that, who have adapted and altered imperial modes to create something different, something better, something less invasive, and who are creative, resilient, positive forces in helping keep marginalised or endangered cultures, heritage, and languages alive and developing new ways of being, sharing resources and living. Those who are refusing old imperial ways of subjugation, control, possession, and domination.

Going back to this question of ‘did Imperialism and colonialism have any benefits’ the very big problem with this is that it fixes us all in a binary narrative constantly concerned about an idea of Western progress as the ONLY one - where there is the underlying assumption that the ‘progress’ brought by colonisers was the singular way forward for humanity to the exclusion of a whole globe full of possible other ways of living a good life as human beings - a binary narrative that disguises and obliterates other possible ways that ‘progress’ could have happened and disguises the violence of the means.

If we keep the narrative rigged to the damaging binary where the West symbolises an idea about the progress that was always ‘meant to be’ and all other ways of seeing and being in the world are backward and traditional then we are at a standstill. There is often an assumption that ‘development’ and ‘progress’ and ‘civilisation’ could only have happened in the way that they did. Embedded in these three terms is the idea that the future is always better than the past without pause for thought. With the violent erasure of other/others’ ways of being that have been labelled ‘backward traditions’ we must ask what have we lost or forgotten? Imperial cultures have more than enough of their own backward traditions but these are also masked in these discussions. This comparative binary always leaves us exhausted, trapped in a single either/or dichotomy. We have to dig ourselves out of this.

The imagery of the colonial postcard women illustrates this problem very well - by showing a certain representation that excludes not only the violence done but that also conceals ALL other possible modes of living and being. There are many ways forward for humanity without relying on a system predicated on racial hierarchies and violent dominance. Forms of representations like the postcard imagery and how we represent issues then dictate the questions we can ask, the language we can use and even what we can think. We need to create new modes that allow us to think beyond this structure and start asking ourselves different questions.

I used to teach at Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. Visitors and students were always obsessed with the Treatment of Dead Enemies display case in the museum. A gory and grotesque display of how ‘indigenous’ peoples treated their enemies. Yet people were always dumbfounded when I asked them how they think Europeans treated and treat their dead enemies? Are modern warfare practices of killing via drone bombing more ‘civilised’ just because it involves advanced ‘technology’? Do they think Western armies carefully respectfully bury their dead enemies?

I also attempted to get students to study and consider the complex technologies that so-called indigenous peoples around the world used to create sustainable lives for themselves and to ask ‘how can we learn from them, how can we learn from others?’ The framework of the anthropological museum itself is, like the postcards of women, yet another representational framework where those whose cultures and objects appear in it are automatically considered ‘primitive’, less advanced, less intelligent, having less useful ideas and technologies and consigned to a quaint past. It is always very instructive to look at whose cultures/what objects are in the Pitt Rivers museum …

When you start adding in all the complex meanings and histories behind the jewellery, textiles, and beautiful crafts shown along with the bodies of women, you begin to also release multiple new potentials/ways of being. Ornament, craft, jewellery, body adornments, and textiles relate to the woman’s body in public and private, social and political ways, to her gestures, movements, visibility and agency. The stifling portfolio of body poses and gestures given to women on colonial postcards imprisons women by binding them to a false history of limited movements, lounging, gazing, smoking, sitting inside the home, silent, inactive, laden with the weight of inappropriate clothing, unimportant, uninvolved in the unfolding new worlds, manipulated and moulded, and staring out at us from these photographs printed on cardboard like so many playing cards being shuffled from one era to the next where the game for them never changes. The more we dig into their multiple ethnicities and backgrounds and realities the more we find out how far from the truth this was.

Focusing on cultures and ways of being that have been eroded can teach us a lot going forward. It’s not that we can or want to go back and live in some naive past where everything was perfect, nor to reject what is positive in our time - and what is positive was not gained ‘because’ of imperialism, we have all contributed to those positives, we were not handed them ready on a plate by the West.

We can think of Imaginarium as a kind of ritual where acts of speaking, art-making, research, and writing are the gestures of self-determination and empowerment. And men and women of the Middle East and North Africa can all get involved in talking about what got left behind or was erased in the narratives of the colonial and the ‘modern’ and help us imagine new worlds and ways of being that draw on that past whilst looking to make the future better for women, which means better for everyone, in the end. Creating a more collaborative, kinder, and wider network of sharing and conversations that focus on what is beneficial to everyone, and working to create alternative non-divisive networks of dialogue and connections with each other, with minority groups and with neighbouring countries.

I also attempted to get students to study and consider the complex technologies that so-called indigenous peoples around the world used to create sustainable lives for themselves and to ask ‘how can we learn from them, how can we learn from others?’ The framework of the anthropological museum itself is, like the postcards of women, yet another representational framework where those whose cultures and objects appear in it are automatically considered ‘primitive’, less advanced, less intelligent, having less useful ideas and technologies and consigned to a quaint past. It is always very instructive to look at whose cultures/what objects are in the Pitt Rivers museum …

When you start adding in all the complex meanings and histories behind the jewellery, textiles, and beautiful crafts shown along with the bodies of women, you begin to also release multiple new potentials/ways of being. Ornament, craft, jewellery, body adornments, and textiles relate to the woman’s body in public and private, social and political ways, to her gestures, movements, visibility and agency. The stifling portfolio of body poses and gestures given to women on colonial postcards imprisons women by binding them to a false history of limited movements, lounging, gazing, smoking, sitting inside the home, silent, inactive, laden with the weight of inappropriate clothing, unimportant, uninvolved in the unfolding new worlds, manipulated and moulded, and staring out at us from these photographs printed on cardboard like so many playing cards being shuffled from one era to the next where the game for them never changes. The more we dig into their multiple ethnicities and backgrounds and realities the more we find out how far from the truth this was.

Focusing on cultures and ways of being that have been eroded can teach us a lot going forward. It’s not that we can or want to go back and live in some naive past where everything was perfect, nor to reject what is positive in our time - and what is positive was not gained ‘because’ of imperialism, we have all contributed to those positives, we were not handed them ready on a plate by the West.

We can think of Imaginarium as a kind of ritual where acts of speaking, art-making, research, and writing are the gestures of self-determination and empowerment. And men and women of the Middle East and North Africa can all get involved in talking about what got left behind or was erased in the narratives of the colonial and the ‘modern’ and help us imagine new worlds and ways of being that draw on that past whilst looking to make the future better for women, which means better for everyone, in the end. Creating a more collaborative, kinder, and wider network of sharing and conversations that focus on what is beneficial to everyone, and working to create alternative non-divisive networks of dialogue and connections with each other, with minority groups and with neighbouring countries.

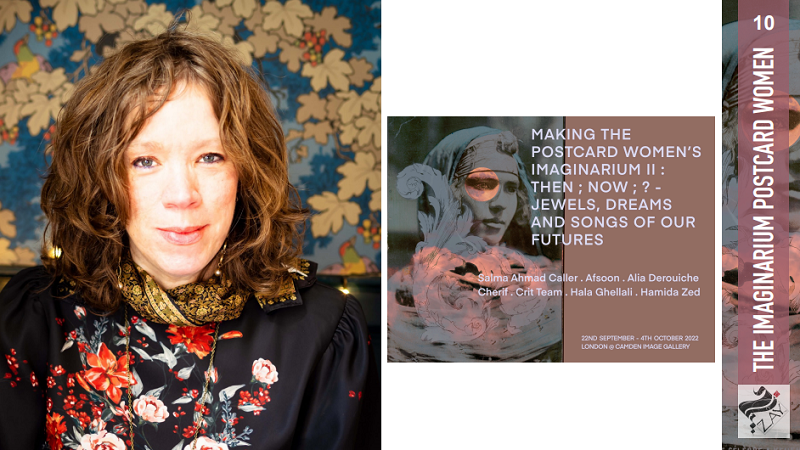

Salma Ahmad Caller was born in Iraq to an Egyptian father and a British mother and grew up in Nigeria and Saudi Arabia. She now lives in the UK. An artist, art historian and writer who is a hybrid of cultures and faiths she is drawn to hybrid and ornamental forms, and to how the body expresses itself in the mind to create an embodied ‘image’. She is particularly interested in cross-cultural and in mixed-race identities, experiences and embodiment. Her work embraces collage, drawing, watercolour, photography, projection, installation and sound. Salma also writes art theory, poetry and creative non-fiction, with a theoretical background in research on the meanings of ornament in non-Western cultures through frameworks of anthropology of art and cognitive science, with the aim of contributing to the decolonisation of art history and theory and breaking down boundaries and categories that support hegemonic colonial and patriarchal formations.

With a Masters in art history and art theory, a background in medicine and pharmacology, and several years of teaching cross-cultural ways of seeing via non-Western artefacts at Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, she now works as an independent artist and teacher.