Traditional Palestinian embroidery is known for its rich colours and stylised motifs but even scholars are unsure about its true origin. The oldest existing piece dates from the first half of the 19

th century. Most of its recorded history covers the era between then and the mid-20

th century, with the establishment of the State of Israel and the large-scale disruption of the Palestinian way of life.

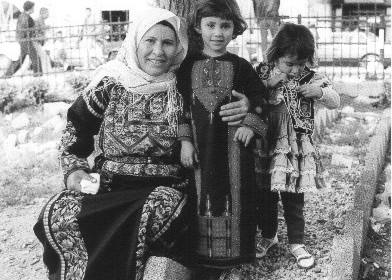

Bethlehem women

Social Fabric:

Palestinian society and their style of dress can be divided into three distinct categories -

Village women (

fellaheen) who lived simple lives in relative isolation. Their embroidery styles, use of colour, and the range of stitched motives were distinct to their respective villages. Their garments were made from linen or cotton woven on hand-looms and coloured with natural dyes.

Town people (

beladin) had more access to outside influences. Their garments often depicted the latest fashions, or the use of textiles, colours and embellishments acquired from Syria. Some producers in Aleppo and Damascus catered specifically to the Palestinian market. By the early 20

th century, these women were the first to adopt a western style of dress.

The

Bedouin were nomadic people whose style of dress reflected their tribal affiliations rather than their geographical location. Their garments were usually made from woven fabric from camel, sheep or goat wool. The same fabric was also used to create their tents and other household items.

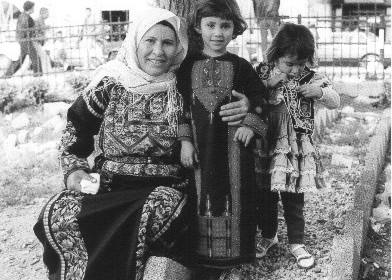

Ramallah woman and children

Garments:

Dresses were not tailored or form-fitting. Women preferred voluminous dresses as these were cooler in the hot climates and more modest. The generous use of fabric also indicated wealth and prestige.

A basic dress (

thawb

Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe

Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe

Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe

Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. ) was a loose-fitting robe with triangular sleeves. Styles differ but dresses usually had an embroidered square chest panel and back panel. This was accompanied by different styles of a jacket or outer garment.

The shape and style of headdresses differed from region to region and most women decorated theirs with gold and silver coins, indicating the wealth of the wearer.

Colours were determined by the availability of natural dyes and differed from region to region.

Indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. was a popular choice as the blue colour was believed to protect against the ‘evil eye’. Dark blue indicated wealth as it meant the person could afford to dip the cloth in the dye multiple times. Other colours were obtained from insects and pomegranates (red), saffron and vine leaves (yellow), oak bark (brown), crushed murex shells (purple).

Bethlehem style breast panel

Embroidery:

Hand-spun and dyed threads were used until the 1930s when imported silk threads and commercially produced DMC threads became available. In most areas, the basic cross stitch was the most widely used stitch with regional variations.

In

Galilee women used a

satin

Sātin: (Arabic: Zaytuni: from Chinese port of Zayton in Quanzhou province where it was exported from and acquired by Arab merchants), one of the three basic types of woven fabric with a glossy top surface and a dull back. Originated in China and was fundamentally woven in silk. stitch, running stitch and drawn-thread work.

In

Bethlehem women, influenced by military uniforms and church vestments, started using

couching

Couching: (Latin: collocare – Place together), in needlework and embroidery couching is a technique in which yarn or other materials are laid across the surface of the ground fabric and fastened in place with small stitches of the same or a different yarn

in their work. This later spread to other parts of southern Palestine.

Dresses from

Nablus had very little embroidery. These women worked long hours in the fields and considered too much embroidery as a sign of idle hands and frivolity.

The

Hebron area was famous for its colourful cross-stitch work and a variety of motifs.

In

Jaffa, a coastal town known for the cultivation of fruit, the embroidery motifs depicted organic shapes, flowers and foliage.

The

Gaza area included the town of

Majdal

Majdal: a scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head.., a major centre for weaving and fabric production. The popular coloured striped fabric is typical of this region.

The Bedouin tribes of the

Negev and Sinai, a desert region, all wore black dresses. Single women and widows decorated their garments with blue stitching and only added pink or red embroidery to their garments once they were (re)married.

Dresses from the Tiraz collection

Learning Embroidery:

Embroidery was done exclusively by women and the skills and traditions were passed on from generation to generation. Girls started learning basic skills from as young as six – as soon as they are able to work with a needle. They start out with scraps of textiles and were taught by copying designs done by their elders.

Patterns and designs unique to her village were passed on and taught like a complex system of visual communication almost like learning a new language - different stitches for different parts of a garment and the right way to combine different motives. Although they all spoke the same language, each village had their own ‘dialect’ which the girls had to learn and understand from early childhood.

Young girls spent most of their time working on their own trousseau or dowry (

jihaz). This included everything she would need as a young bride and married woman – unadorned everyday dresses, highly decorated dresses for special occasions, veils and headdresses, undergarments, belts and footwear.

Dress from the Jaffa area

Displacement:

First, the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 and later the Six Day war in 1967, resulted in large-scale displacement of people from Palestinian villages. Most of these people have since lived in refugee camps in Gaza, the West Bank, and neighbouring countries.

Not only did villagers lose their individual styles and motifs, but now Palestinian dress and embroidery became an expression of nationalism and patriotism, depicting the national colours, the flag and other political statements. Those who still made their own dress were influenced by designs from other regions and a new ‘Palestinian’ style emerged.

Financial hardship and desperate conditions forced women to do embroidery – their only skill – as a means of creating an income. Different welfare organisations created programs for women to make non-traditional items for market including cushion covers, scarves, tablecloths, handbags, and others.

Dress from the Bethlehem area

Museums and Collections:

Thanks to visionaries like

Widad Kawar, several collections of original Palestinian dress and embroideries exist and are being documented and recorded. Ms Kawar collected samples of dress from village women throughout Palestine all the while recording the women’s stories and documenting the different styles and patterns from each region. Her collection can be seen at the Tiraz Centre in Amman, Jordan.

Shelagh Weir former curator for Middle Eastern ethnography at the British Museum conducted intensive field studies in Palestine, curated several exhibitions and published five books on Palestinian embroidery and costume.

The

Israel Museum in Jerusalem holds one of the largest collections of Palestinian dress.

Exhibit in the Tiraz Centre, Amman

Sources:

- Shelagh Weir: Embroidery from Palestine – The British Museum Press, 2006

- Shelagh Weir: Palestinian Costume – Interlink Books, 2009

- Margarita Skinner & Widad Kamel Kawar: Palestinian Embroidery Motifs – Rimal Publications, 2007

- Images from the collections of the Tiraz Centre in Amman and the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka

Bethlehem women

Bethlehem women Ramallah woman and children

Ramallah woman and children Bethlehem style breast panel

Bethlehem style breast panel Dresses from the Tiraz collection

Dresses from the Tiraz collection Dress from the Jaffa area

Dress from the Jaffa area Dress from the Bethlehem area

Dress from the Bethlehem area Exhibit in the Tiraz Centre, Amman

Exhibit in the Tiraz Centre, Amman