Couching: (Latin: collocare – Place together), in needlework and embroidery couching is a technique in which yarn or other materials are laid across the surface of the ground fabric and fastened in place with small stitches of the same or a different yarn

or tahriry Taḥrīry: (Arabic) couching embroidery technique developed in Bethlehem. Differs from the predominantly cross-stitch style of embroidery found in the rest of Palestine. embroidery.Couching: (Latin: collocare – Place together), in needlework and embroidery couching is a technique in which yarn or other materials are laid across the surface of the ground fabric and fastened in place with small stitches of the same or a different yarn

embroidery. As Bethlehem was a popular tourist and pilgrimage destination, as well as a commercial hub, the craft industry blossomed along with the economy of the town.The Bethlehem costume is called royal because it is so rich that it is described as ‘the queen of dresses’ in Palestine. Indeed, it is made of a blend of silk and linen, woven in bright multi-coloured stripes. Over the dress comes a short-sleeved jacket that glistens with embroidery. With this costume, women wear high, fezFez: (Ottoman Turkish: fes boyası - madder

-like headdresses bearing the glinting coins of their dowry, crowned by a sheer shawl Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. . Religious harmony was demonstrated by the fact that both Christians and Muslims wore the same style, with Christian women adding a small cross on the chest panel of their costumes.Madder: (Latin: Rubia tinctorum – Eurasian herb), rose madder, common madder or dyer's madder is a vegetable dye made from the roots of a perennial plant belonging to the bedstraw and coffee family. It has been used extensively as a vegetable red dye across the globe from India to England.

to Arabic Fez – Moroccan city; Synonym: tarboushṬarbūsh: (Turkish: terpos – turban; from Persian serposh – headdress; Synonym: fez), a type of traditional skull cap with a high crown. With a possible Mediterranean origin, this head wear gained popularity in the late Ottoman period and became the forerunner of other similar caps with slight variations.

), a type of traditional skull cap with a high crown. With a possible Mediterranean origin, this headwear gained popularity in the late Ottoman period and was named after the Moroccan city where the dye was extracted.

(p.136-137 Threads of Identity – Preserving Palestinian Costume and Heritage by Widad Kamel Kawar)

The malak was the most important item for a trousseau and was always donated by the groom. The provision of the headdress, or shatweh, with coins and the jewellery for the marriage, was the responsibility of the bride’s father and was looked upon as the rightful share of the bride-price. The shatweh was essential for the wedding dress. A festive veil was worn over it.

(p.15 Palestinian embroidery motifs 1850-1950. A Treasury of Stitches by Margarita Skinner in association with Widad Kamel Kawar)

Couching: (Latin: collocare – Place together), in needlework and embroidery couching is a technique in which yarn or other materials are laid across the surface of the ground fabric and fastened in place with small stitches of the same or a different yarn

to pieces already decorated with the local cross-stitch designs. Her designs became so popular that she started her own business.She would take the Beit Dajan embroidery pieces to Bethlehem to be embellished by Jamila Hazboun Mahyub, or at the workshops run by the Hazbouns. At first, the work added in Bethlehem consisted only of rose branches on the skirt, but then some wanted it on the chest panel too. Later on, Manneh’s mother and brother help her start a workshop where she taught Beit Dajan girls Bethlehem style embroidery, including new connecting stitches, couchingCouching: (Latin: collocare – Place together), in needlework and embroidery couching is a technique in which yarn or other materials are laid across the surface of the ground fabric and fastened in place with small stitches of the same or a different yarn

, and applique.

(p.158 Threads of Identity – Preserving Palestinian Costume and Heritage by Widad Kamel Kawar)

While the malak is made of striped silk and linen fabric specific to Bethlehem, the khaddameh uses plain linen without stripes. Similarly, the malak is embroidered on the chest panel and sides with an ornate couchingCouching: (Latin: collocare – Place together), in needlework and embroidery couching is a technique in which yarn or other materials are laid across the surface of the ground fabric and fastened in place with small stitches of the same or a different yarn

stitch, while the khaddemeh’s chest panel is embroidered with the simpler and less costly cross stitch. The sleeves of this dress are done in the kumm ‘irdanIrdān: (Arabic: ridān – sleeve), long triangular winged cuffed sleeves of a robe from the Levant Arb region, especially Palestine, Jordan, and Syria. The triangular cuffs were usually a decorative addition that were often tied at the back of the dress while doing regular chores.

style in which the sleeves are long, pointed, and triangular. The wearer of this dress would tie the two sleeves behind her back while working to make movement easier.

(Excerpt from The handwoven History of Palestine and Jordan, published by the Tiraz Centre

The fabric from which the thob was made were usually narrow, no more than 16 to 20 centimetres, so the style of the dress was determined by the width of the fabric. A length of fabric was taken to match the height of the woman and then doubled to form the front and back of the dress. To give the dress the desired width, banayek Banāyiq: (Arabic) two long triangles inserted along the sides of the Palestinian thawb Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. , to give more width to the dress. (two long triangles were cut and inserted in the sides. The sleeves were set in a straight cut: for winged sleeves, a triangle was added. Sometimes, a square was cut separately, embroidered and sewn on as a qabeh (breast piece).

(p.60-61 Threads of Identity – Preserving Palestinian Costume and Heritage by Widad Kamel Kawar)

Couching: (Latin: collocare – Place together), in needlework and embroidery couching is a technique in which yarn or other materials are laid across the surface of the ground fabric and fastened in place with small stitches of the same or a different yarn

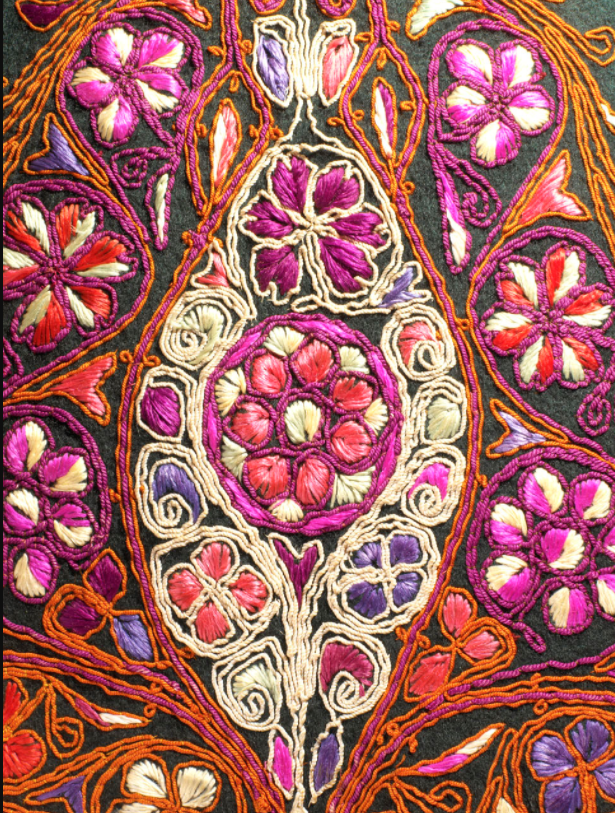

design with satin Sātin: (Arabic: Zaytuni: from Chinese port of Zayton in Quanzhou province where it was exported from and acquired by Arab merchants), one of the three basic types of woven fabric with a glossy top surface and a dull back. Originated in China and was fundamentally woven in silk. stitch. Image credit: Palestinian Heritage FoundationCouching: (Latin: collocare – Place together), in needlework and embroidery couching is a technique in which yarn or other materials are laid across the surface of the ground fabric and fastened in place with small stitches of the same or a different yarn

or tahriry Taḥrīry: (Arabic) couching embroidery technique developed in Bethlehem. Differs from the predominantly cross-stitch style of embroidery found in the rest of Palestine. embroideryCouching: (Latin: collocare – Place together), in needlework and embroidery couching is a technique in which yarn or other materials are laid across the surface of the ground fabric and fastened in place with small stitches of the same or a different yarn

refers to an embroidery technique where a thread or cord is laid flat on the surface of the fabric and then sewn into place with small, almost invisible stitches across. The cord can be laid to create different patterns, designs, and motifs. Cords or laid threads can vary from cotton and silk to silver or gold ribbons. In the Bethlehem or tahriry Taḥrīry: (Arabic) couching embroidery technique developed in Bethlehem. Differs from the predominantly cross-stitch style of embroidery found in the rest of Palestine. style, couchingCouching: (Latin: collocare – Place together), in needlework and embroidery couching is a technique in which yarn or other materials are laid across the surface of the ground fabric and fastened in place with small stitches of the same or a different yarn

is used as an outline and to define a pattern, which is then filled in with satin Sātin: (Arabic: Zaytuni: from Chinese port of Zayton in Quanzhou province where it was exported from and acquired by Arab merchants), one of the three basic types of woven fabric with a glossy top surface and a dull back. Originated in China and was fundamentally woven in silk. stitch.The distinctive patterns were applied to specific parts of the dresses, making them recognisable as Bethlehem styles. For example, the sleeves were embroidered with a pattern called “watches” in the couchingCouching: (Latin: collocare – Place together), in needlework and embroidery couching is a technique in which yarn or other materials are laid across the surface of the ground fabric and fastened in place with small stitches of the same or a different yarn

technique, repeated three times. So were the side panels, which also had a pattern called ‘tree of life’ in cross-stitch evolving above ‘watches.’

(Extract from The Queen of Dresses: The Malak, produced by The Tiraz Centre)