Imaginarium Postcard Women - Part 1

Colonial Collecting and introducing Colonial Postcards of Women

by: Salma Ahmad Caller

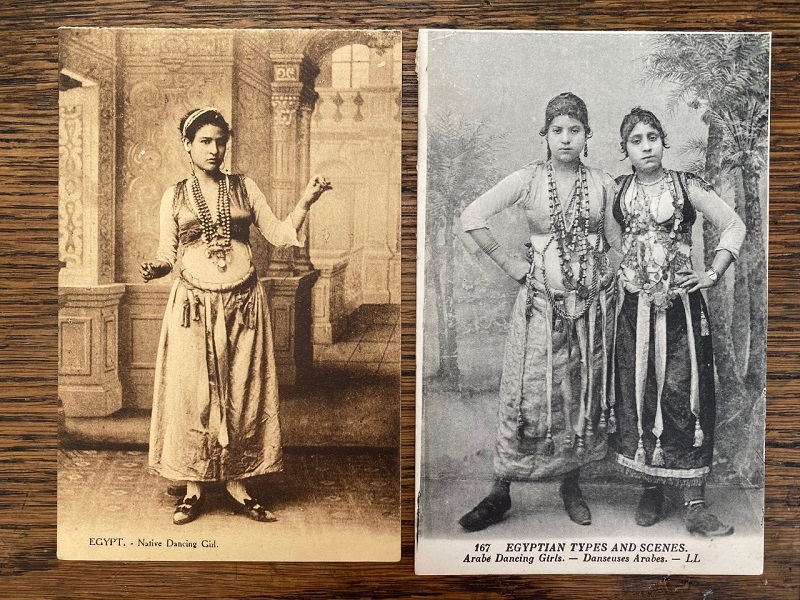

To briefly encapsulate it, the colonial postcard was generated during the period of European expansion of its empires in the late 1800s to the early/mid-1900s. The colonial postcard was created, using the new printing technologies of the time, to print photographic images, mostly taken by Europeans, onto millions of cards then also disseminated by Europeans, representing the nonwestern non-European world according to European ideologies and frameworks. The postcards themselves, the medium of the postcard as a disseminator of ideologies, and the photographs used to create them are all deeply entangled in the imperial project to control and subjugate other countries by various means including violence and racial stereotyping, in the exoticism of others and in pseudoscientific racial anthropology of the time.

Invariably the colonial postcard was also part of an Orientalist visual system of representing the ‘east’ by the ‘west’. Orientalist photography and painting of this era mostly created a false scopic regime or imagery, that visually structured how those people and their cultures, heritage, clothing, and social behaviours were understood or rather misunderstood. A system consisting of richly detailed evocative images ‘revealing’ or unveiling a mysterious, seductive, erotic, exotic, morally bankrupt, available ‘East’ stuck in an ancient past bound by static religious and cultural traditions that were deemed to be backward in opposition to a developing, modernising and civilised ‘West’. Beyond this generalised definition, there is, of course, a lot of complexity based on variations in local experiences, degrees of colonial interference and violence, and kinds of imagery. Behind the colonial image on the postcard are, as briefly mentioned, several other problematic structural ideologies of the time, including the pseudo-scientific construction of race where white Europeans were placed at the top of a hierarchy, and included anthropology and popular ethnography that fed into the construction of race by showing the peoples of the non-white world as exemplifying and upholding this theory as types and stereotypes.

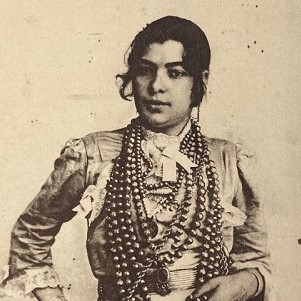

Cairolady

I found my first Egyptian colonial postcard of a woman - labelled ‘a type of a Cairolady’ in 2018 at Spitalfields Market in London. At first, I thought this was an accurate record of a woman from a past time in Cairo. As a mixed-race Egyptian British artist searching for my ‘true’ identity I felt this was an important find. I felt a connection. That this woman mattered. But it wasn’t until I turned over to look at the back of the postcard that I realised how much she would begin to matter. That she was both a ‘real’ Egyptian woman and NOT at the same time. That duality and complexity are what makes these postcards so fascinating, important to study and decolonise. I felt she was like me, both Egyptian and not at the same time.

The writing on the back in English from the 19th century spoke about how these women ‘look ok on postcards but as you pass them by on the street you can smell them’. The author of the postcard asks the sender to please keep all the postcards that he sends as he wants to use them when he gets back. This remains one of the most significant postcards in my collection. Right from the start, it points to the multiple ways in which Middle Eastern / North African women were perceived at that time. As fascinating, intriguing, collectable, easily categorised and possessed, denigrated, and admired at a glance or in one sentence on a postcard. He obviously wanted a ‘full set’…

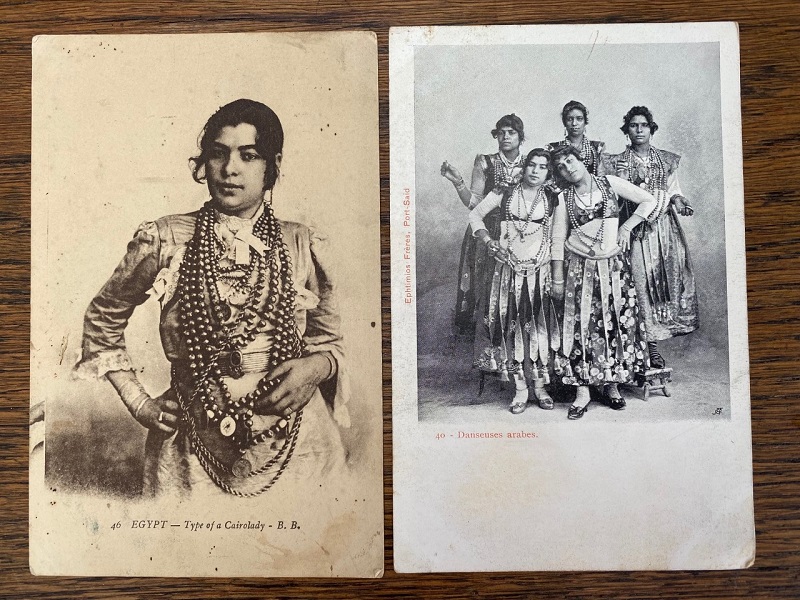

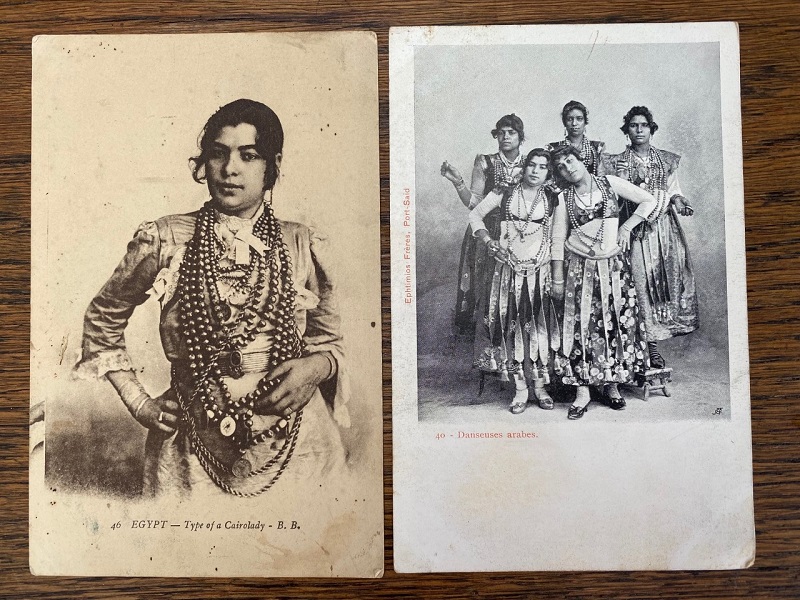

The disturbing writing on the back prompted me to try to see if I could find out who this woman really was. Surprisingly I was almost able to, which is very unusual regarding such postcards, where true identities must mostly remain forever unknown. My second postcard find shows this same woman, dressed very differently, standing together with a dance troupe of Egyptian Ghawazee dancers sent to perform as part of the Chicago world fair of 1893 celebrating the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the so-called New World in 1492. The fair had a ‘Turkish’ cafe, a ‘Persian’ theatre and a ‘Street in Cairo’ with performers and dancers, some of whom, like the dancer, ‘Little Egypt’ was not Egyptian at all. And, of course, we must ask if this troupe shown here were actual Ghawazee or a troupe performing dance in the style of the Ghawazee?

Marginal Women

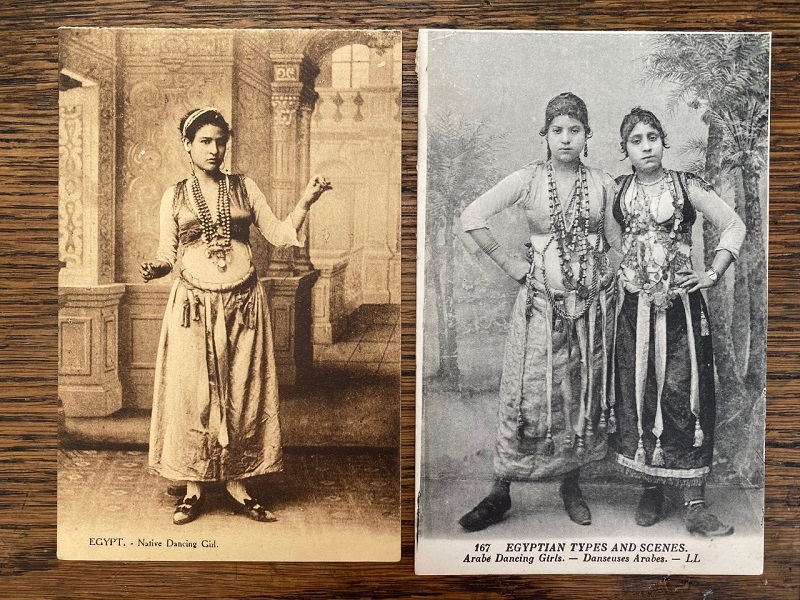

They are very typical of the ‘types’ of women appearing on colonial postcards, who were more often than not, lower working-class women, enslaved women, sex workers, domestic servants, women working as dancers, entertainers, musicians, fortune tellers. Women on the margins of society. The Ghawazee were decedents of nomads who migrated from India, through Iran and Kurdistan around the 16th century. With their own distinct culture, a language with elements of Hindi and Farsi, and with professions as dancers and entertainers for both large and small important cultural events like weddings, circumcisions, moulids, they were seen as both outsiders in Egypt as well as being an important part of local traditions.

They were described by Orientalist Edward Lane Fox, but more famously, they wrote about by Gustave Flaubert in Egypt, where he both sumptuously and disturbingly describes Kuchuk Hanem and other ‘negresses’, Nubians and ‘Abyssinian slaves’ in highly sexualised language. The black bodies are particularly inscribed with ‘savage’ and primal desires. Flaubert describes all their clothing and jewellery in very intricate, richly descriptive ornamental and sensual detail. This pairing of quasi- ethnographic ekphrastic descriptions with a strong language of immorality, seduction, dirt, and abandon could be described as a qualifying feature of much of the kinds of writings and imagery of this period. Many colonial postcards mix these same elements together in how they depict women. The level of ‘ethnographic’ ‘authentic’ detail was used to add credence and credibility to fantasy.

Flaubert describes Kuchuk’s triple necklace of large golden hollow beads that we can see on my ‘Cairolady’ postcard, in the context of her skin colour, her decaying tooth, her tarboosh, a fake emerald green stone, her gold disk earrings decorated with golden granules, and a tattoo - a blue line of writing on her arm. The Ghawazee troupe on my second postcard can also be seen wearing these beads, and they are wearing the three golden tassels he describes hanging from girdles. The ‘Nubians’ and ‘Negresses’ as he calls them, wear long chains of silver coins reaching to their thighs, and circles of coloured beads sit around their hips, pointing to other ethnicities and origins.

It is well known that Muhammad Ali Pasha banished the dancers to Upper Egypt for their supposed immortality, and Flaubert finds Kuchuk again much later in Esna reduced to poverty, but there are also accounts of how Ghawazee women led more empowered lives as breadwinners. They were not required to marry and if they did, the men were subservient to them and often worked as musicians in their troupes. These were independent women who travelled abroad, made all the decisions, and refused to follow government rules or the rules of men, either in Egypt or when touring in America. European women ‘lady managers’ at the Chicago world fair were outraged by their dancing and wrote petitions and letters to have them restrained. But the fairs made big money from their dance shows. These conflicting narratives show these women as possibly having had far more agency compared to other women of their time in Cairo, although in the end they were forced to near extinction by religious and patriarchal conservatives in power.

Photographers and Studios

Of course, not all women on postcards are lower class. Far from it. Many women from different social classes and worlds were portrayed in different ways, by numerous different kinds of photographers and studios emerging at the time. But they all fall within the same problematic frameworks, ideologies, and political social climate of the late 1800s/early 1900s. And we must start here because these women are the ones most used and subjected to a certain kind of imagery and system of representation emerging out of Europe and being used by European photographers and their studios.

Studios were set up in Egypt (Cairo and Port Said mainly), Tunisia (a huge number of exploitative erotic postcards of young underage Tunisian girls were generated by Lehnert & Landrock Tunisian studios who are still lauded today for their images of monuments of the Middle East), Istanbul (Pascal Sebah) and Beirut (Bonfils studio). Hundreds of thousands of images were generated. Millions even, and then printed onto postcards over decades. Such a high level of imagery exploding out everywhere in Europe carried a huge weight of visibility and ability to disseminate ideas about these regions of the world.

I use the word image to evoke the notion that what you see on a postcard is not really a reality or truth either about that woman or where she was from. Some truth perhaps, and the rest fantasy and construction. It is vital to unpick all the layers of framing that accompany such imagery that would have determined in what ways such postcard women were perceived. To excavate the multiple complex layers of representations that framed the postcards of women from the MENA region, we must start with an understanding of the circumstances of the emergence and development of photography as the daguerreotype in 1839, and go back even earlier to 1750 to look at the evolving pseudo-science of racial stereotyping, and the way in which these racist concepts were integral to and foundational for the development of fields of ethnography, popular ethnography, anthropology, Egyptology, art history and photography.

Bibliography and Additional Reading

- Images of Women: The Portrayal of Women in Photography of the Middle East 1860 - 1950 by Sarah Graham-Brown

- Camera Orientalis by Ali Behdad

- Flaubert in Egypt by Gustave Flaubert

- Photography and Egypt by Maria Golia

- Remaking Women: Feminism and Modernity in the Middle East edited by Lila Abu-Lughod

- Rethinking Orientalism: Women, Travel and the Ottoman Harem by Reina Lewis

- Ethnopornography: Sexuality, Colonialism, and Archival Knowledge ed. Pete Sigal, Zeb Tortorici & Neil L. Whitehead

About the Author

Salma Ahmad Caller was born in Iraq to an Egyptian father and a British mother and grew up in Nigeria and Saudi Arabia. She now lives in the UK. An artist, art historian and writer who is a hybrid of cultures and faiths she is drawn to hybrid and ornamental forms, and to how the body expresses itself in the mind to create an embodied ‘image’. She is particularly interested in cross-cultural and in mixed-race identities, experiences and embodiment. Her work embraces collage, drawing, watercolour, photography, projection, installation and sound. Salma also writes art theory, poetry and creative non-fiction, with a theoretical background in research on the meanings of ornament in non-Western cultures through frameworks of anthropology of art and cognitive science, with the aim of contributing to the decolonisation of art history and theory and breaking down boundaries and categories that support hegemonic colonial and patriarchal formations.

With a Masters in art history and art theory, a background in medicine and pharmacology, and several years of teaching cross-cultural ways of seeing via non-Western artefacts at Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, she now works as an independent artist and teacher.