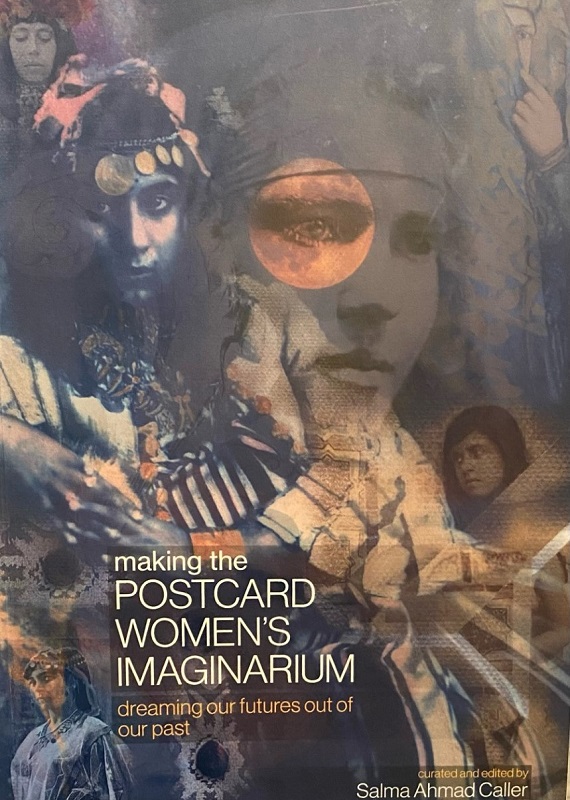

This essay called Our Narrative - A Trilogy was published in

Making the Postcard Women’s Imaginarium: Dreaming our Futures out of our Past, a book curated and edited by Salma Ahmad Caller and published by

Peculiarity Press. It was published as part of the Making the Postcard Women's Imaginarium Then; Now? exhibition at Camden Image Gallery in London. The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative was invited to participate in this project as a content partner. This personal account by The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative founder, Dr Reem el Mutwalli, explores her family heritage and how it has shaped and informed her identity as well as the work of The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative.

My family arrived in what is now the UAE from Iraq in 1968 when I was around five years old. I think most families who leave their home country and don't ever return are left with a deep longing, of wanting to hold on to their heritage, to who they are through their possessions. My earliest memory, I might have been about four or five, is of colour. Lots of colour; ruby reds, and emerald greens, whether it be found on my mother's fingers or on the rugs, paintings, and tapestries that filled our home. As such, my appetite for all things artistic and beautiful was solidified at home and continued to develop as I grew up.

For my undergraduate degree, I majored in interior design, I continue to practice, through my firm, creating sanctuaries and establishing individual art collections for select clients. For my masters degree, I read Islamic architecture, which led to a survey of the forts and fortifications in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, culminating in the publication of the book Qasr al Husn: An Architectural Survey (1995). This anchored my role in promoting culture and art as I headed the Exhibition & Arts department at the Cultural Foundation Abu Dhabi for over twenty years. For my doctorate, I studied Islamic art and archaeology, continuing this notion of the preservation of tradition and the protection of heritage.

The subjects I chose to pursue consciously or unconsciously drew from my life in the UAE, and the blessing it has bestowed on me. My experience of wearing UAE clothing as I grew up in the community here played a role in my decision to research the topic of dress and its evolution in the UAE. So I began gathering the UAE collection, which I dubbed

Sultani

Sulṭānī: (Arabic: sultān: king). In the UAE the term denotes to silk satin fabric in multiple vertical striped colours, commonly used for tunics (kanadir) and underpants (sarāwīl). Also refers to book: Sultani, Traditions Renewed, Changes in women’s traditional dress In the United Arab Emirates during the reign of the late Shaykh Zāyid Bin Sultan āl Nahyān, 1966-2004, By Dr. Reem Tariq

Ṭariq: (Arabic; Synonym: tulle_bi_talli; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the Levant Arab region specifically in Lebanon.

El Mutwalli (2011)., organically. As I worked on my doctorate, I found myself in the fortunate position of being the recipient of many of the dresses illustrated in my thesis which later was published;

Sultani

Sulṭānī: (Arabic: sultān: king). In the UAE the term denotes to silk satin fabric in multiple vertical striped colours, commonly used for tunics (kanadir) and underpants (sarāwīl). Also refers to book: Sultani, Traditions Renewed, Changes in women’s traditional dress In the United Arab Emirates during the reign of the late Shaykh Zāyid Bin Sultan āl Nahyān, 1966-2004, By Dr. Reem Tariq

Ṭariq: (Arabic; Synonym: tulle_bi_talli; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the Levant Arab region specifically in Lebanon.

El Mutwalli (2011). - Traditions Renewed: Changes in Women!s Traditional Dress in the UAE during the reign of Shaykh Zâyid bin Sultân Âl Nahyân 1966-2004.

The first edition of the book was issued in 2011, at the time, The

Sultani

Sulṭānī: (Arabic: sultān: king). In the UAE the term denotes to silk satin fabric in multiple vertical striped colours, commonly used for tunics (kanadir) and underpants (sarāwīl). Also refers to book: Sultani, Traditions Renewed, Changes in women’s traditional dress In the United Arab Emirates during the reign of the late Shaykh Zāyid Bin Sultan āl Nahyān, 1966-2004, By Dr. Reem Tariq

Ṭariq: (Arabic; Synonym: tulle_bi_talli; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the Levant Arab region specifically in Lebanon.

El Mutwalli (2011). Collection encompassed 180 traditional UAE dresses. Today, The

Sultani

Sulṭānī: (Arabic: sultān: king). In the UAE the term denotes to silk satin fabric in multiple vertical striped colours, commonly used for tunics (kanadir) and underpants (sarāwīl). Also refers to book: Sultani, Traditions Renewed, Changes in women’s traditional dress In the United Arab Emirates during the reign of the late Shaykh Zāyid Bin Sultan āl Nahyān, 1966-2004, By Dr. Reem Tariq

Ṭariq: (Arabic; Synonym: tulle_bi_talli; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the Levant Arab region specifically in Lebanon.

El Mutwalli (2011). Collection makes up 700 artefacts of the larger

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative Collection that is home to, not only Emirati dress but more than 1500 ethnic textiles and traditional costumes from all over the Arab world. The term ‘Arab world’ encompasses and is inclusive of many different ethnicities, cultural practices, religions and dialects.

The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative’s focus, at present, is on growing a traditional dress collection with examples from across the Arab world alongside relevant pieces from Iran, India, China, Ottoman Turkey and elsewhere, that highlight the exchange of historical influences along the Silk Road. The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. continues to add new acquisitions while engaging with and promoting existing collections, to encourage collaboration, knowledge exchange and the preservation of our heritage. We launched the first regional digital archive of pieces from our collection and the Initiative is home to an ever-expanding glossary and dictionary for regional and historic dress terminology in both English and Arabic. The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative!s tagline

‘an ode to the past, a nod to the future’ refers to our commitment to fortify our future by honouring our history. The future has no meaning without understanding our past, and our past becomes irrelevant if we cannot apply the lessons and wisdom to improve our future.

By expanding the collection of Arab dress and adornment, The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative celebrates the human narrative – appreciating that these pieces tell the story of people from all walks of Arab life, mainly women, but also men, who come into this world and leave little trace behind. Collecting cultural heritage, dress and adornment mean gathering together a bountiful rich resource that is often under threat of being lost or misconstrued due to lack of accurate documentation. Through the preservation of these pieces, The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative plays a significant role in fortifying, encapsulating and sustaining a small but important part of Arab history.

‘The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.’

Although this quote from Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie does not refer to Arab heritage, it cuts through to the essence of the issue. The Arab World is a complex, nuanced, multi-layered society, that is very multi-ethnic and diverse, and one picture or one postcard never tells the whole story or even the true story. But a postcard image is still part of a bigger lexicon of stories and histories and should not be dismissed.

The dilemma of identity

Defining my own identity has always been a dilemma for me. My parents are Iraqi, but among Iraqis, I am not Iraqi enough; I grew up in the UAE within Emirati culture, but I am not Emirati enough, I am a naturalised Canadian yet I don't identify solely as Canadian; I have lived and studied in the US and my daughter was born there, yet I am not American enough; now I divide my time between the UAE and the UK, yet I am not British enough. Who am I? I am not any one of them, but rather - I am the sum of them.

To add to the complexity of the subject of identity, for the outside world being Arab and being from the Arab world generally evokes certain stereotypical images. Obscuring the fact that the Arab world is a varied, nuanced, layered society made up of 22 countries, many ethnic groups, and different religions. The impact of colonialism and orientalism on Arabs is such that it also affects our own perception of ourselves and who we feel we are and this impact varies distinctly from person to person, according to generational and experiential differences, specific family histories, and depending upon social and economic situations and how people fit into the multiple layers and hierarchies of the societies that make up the Arab world.

Identity and clothing add yet another layer of complexity. When we put on clothes and adorn ourselves we are telling a story, creating a narrative that shapes how we want others to perceive us. This story changes with individuals, circumstances, time, economic status, and religion. Each individual curates a changing story according to their changing circumstances, economic and social status, religion and so forth.

Identity across generations

It is interesting to draw a comparison between how I feel about my heritage and how my mother and daughter feel about theirs, and moreover, how we choose to represent it in noticeably different ways. My mother, an Iraqi university graduate, born of a Turkish mother, is very sure of her identity as an Iraqi woman. She is confident about who she is, boisterous about her Iraqi-ness, and self-assured about her heritage. She has never dressed traditionally except on formal occasions. Following the end of the old colonial British presence in Baghdad, Iraqis of her generation wore Western dress as a sign of being educated and emancipated; meanwhile, I grew up surrounded by Emirati women who needed to assert their identity within a newly formed country facing an influx of many people from different nationalities, and so they wore their Emirati traditional dress and wore it as everyday attire. Meanwhile, my American-born, Iraqi-Kurdish daughter, who grew up between the USA and UAE, identifies more as a child of the world and doesn't hesitate to remind me, often, that country borders are imaginary, she also chooses to dress in a very practical and contemporary fashion.

Dress as identity

When I sat back and reflected upon the approach that I and in turn the

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative would have taken to make the Postcard Women ‘ours again’, I considered superimposing different articles of dress from The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Collection according to where each Postcard woman was from. But I kept hitting a wall, so to speak. As I began to choose articles of dress to fit with different Postcard women from the Arab world I thought to myself - who am I to make these women dress the way I like just because I presume we are connected in heritage? Am I not doing to the women exactly what the people who took these images did? Dressing them according to what I presumed they would have worn, but not knowing definitively. Would I not then be objectifying them and mislabeling them according to my own fragmented perceptions? I decided that the only way to honestly approach this endeavour, the only way to move away from the static colonial space-time, would be to incorporate women who wanted to partake in this activity, and who were free to do so, in a manner that suited them.

The images that finally emerged for the Imaginarium book and exhibition depict me, my mother, and my daughter each wearing

the same overgarment of Mesopotamian roots, known as Hashmi

Hashmī: (Arabic: Hashim (House of) – an Arab royal family from the Banu Hashim clan of the Quraysh tribe), a type of elaborately decorated women’s traditional garment or thawb from Iraq that was named after the royal family that ruled Iraq until the mid 20th century.

in Iraq. Each of us can be seen wearing the garment in our own style, adding embellishments that suit us that we independently have chosen.

My mother, myself, and my daughter are all connected in lineage but we also are very different in lineage. My mother was born to a Turkish mother and grew up in Bagdad, Iraq. I was raised in the UAE, and have only visited Iraq a handful of times. My daughter who is half-Kurdish, from her Iraqi Kurdish father, was born in the US and has never been to Iraq. But the three of us all feel, on varying levels, a deep connection to our Iraqi roots that led to our mutual decision to wear the same Iraqi

Hashmi

Hashmī: (Arabic: Hashim (House of) – an Arab royal family from the Banu Hashim clan of the Quraysh tribe), a type of elaborately decorated women’s traditional garment or thawb from Iraq that was named after the royal family that ruled Iraq until the mid 20th century.

. In a way, this is the only thing that reflects our sameness, the element of our identity that we share.

Identity and the freedom to choose

We each incorporated our own contemporary Western accessories to complement our individual ‘look’. The manner in which we each decided to style our garments, reflects ownership over ourselves and how we are represented, which we are privileged to have, and we know that not all women have that freedom and control over their representation even today. This is a crucial difference, between us three women across the generations of our family, and the situation that the Postcard women found themselves in. We came together as women and as a family, to pay tribute to those women. It mattered to us to show and reflect on that vital difference and the importance of our ability to choose what we wear. The accessories are fashion brands we chose to incorporate, intentionally or not, that reflects our personal privilege and choice, and show how in this day and age, Arab women may use designers whose ancestors could have claimed lineage from those who took the photographs of the women captured on the colonial postcards. Is this a negative consequence of colonialism? Does this mean they continue to have ownership over us? Or is this a positive? We appreciate the beauty of these items and have independently chosen to wear them on our bodies regardless of where they originate from.

We cannot change the past, but I believe we can learn and grow from it. The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative’s approach is to draw upon our complex histories to inform present-day decision-making. We know who we are and how we want to be portrayed and no one from either East or West should attempt to claim ownership over us, our bodies and our choices. I hope that we can help more women from all ethnicities and backgrounds to be emancipated and empowered so they can eventually have the same freedom of choice as we do about how they are treated and represented, both within our own societies and beyond.

Identity and the dilemma of recorded history

While we must try to understand the complex histories and the contexts of dress, it is never straightforward, and the process of archiving these pieces to save them for future generations is not the same in the Arab world as in other regions. Socio-political circumstances have hindered the path to protecting our heritage or have made it less of a priority. We have a long way to go and so much to develop to reach a level of maturity as far as preservation is concerned. We have few first-person comprehensive bodies of work that can help explain and ground people with a fuller dress knowledge. Our histories have generally been written about us, not by us.

We at The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative also understand the problematic and complex colonial heritage that is associated with museums, their ethnic collections, and the way artefacts were and still are documented in a way that is devoid of the poetic textures and contexts of language, usage, ritual, and oral culture. But we are wary of criticising institutions that have played a role during a specific period. Without them would we have conserved so much of our heritage? We, therefore, feel we cannot dismiss their role and now need to pick up the narrative from our own perspectives and amend and contextualise it appropriately. Building in the layers over time and putting in what has been purposefully or inadvertently left out, to try to rectify the absence of the multiple voices and ethnicities that claim ownership of cultural heritage across boundaries that were once far more porous.

As it stands today, I believe the responsibility falls upon us to sift through and rectify the legacy that we have been dealt. I act on this notion through The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative, where we have taken on the task of preserving and recording, but also educating our fellow Arab people first and foremost, to value their traditions - not just the physical items, such as garments, but the stories and narratives that give these treasured pieces colour. Moreover, with the surge of wealth and increased globalisation in this region, there is now a younger generation that is educated and exposed to the world. This has led to a community of regional designers emerging who are trying to create some sort of representation of the region by drawing on and being inspired by elements from our historical adornment heritage. Many of these designers refer back to orientalist and colonial images as this is sometimes the only record of that piece of heritage available. So here The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative is trying to make a difference, by providing factually correct information and references, whenever possible, to combat misinformation and misunderstanding about our heritage.

Fortunately, technology can help us make this information and knowledge more accessible globally and we are constantly renewing and updating our database, constantly learning and adding to the platform with opinions, blog posts, and webinars. In creating this body of work that people can refer to we hope to facilitate the healing process.

Here at the

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative, we don't claim to have all the answers, but believe empowerment comes from knowledge and supporting women and platforming marginalised voices. Putting artefacts back into context, and recording the names, details and stories of their wearers matters and is our way of reasserting the dignity of both the artefacts and those who wore them.

* Photos copyright © The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative. Photographic editing by Aasiya Jagadeesh.

My family arrived in what is now the UAE from Iraq in 1968 when I was around five years old. I think most families who leave their home country and don't ever return are left with a deep longing, of wanting to hold on to their heritage, to who they are through their possessions. My earliest memory, I might have been about four or five, is of colour. Lots of colour; ruby reds, and emerald greens, whether it be found on my mother's fingers or on the rugs, paintings, and tapestries that filled our home. As such, my appetite for all things artistic and beautiful was solidified at home and continued to develop as I grew up.

For my undergraduate degree, I majored in interior design, I continue to practice, through my firm, creating sanctuaries and establishing individual art collections for select clients. For my masters degree, I read Islamic architecture, which led to a survey of the forts and fortifications in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, culminating in the publication of the book Qasr al Husn: An Architectural Survey (1995). This anchored my role in promoting culture and art as I headed the Exhibition & Arts department at the Cultural Foundation Abu Dhabi for over twenty years. For my doctorate, I studied Islamic art and archaeology, continuing this notion of the preservation of tradition and the protection of heritage.

The subjects I chose to pursue consciously or unconsciously drew from my life in the UAE, and the blessing it has bestowed on me. My experience of wearing UAE clothing as I grew up in the community here played a role in my decision to research the topic of dress and its evolution in the UAE. So I began gathering the UAE collection, which I dubbed Sultani

Sulṭānī: (Arabic: sultān: king). In the UAE the term denotes to silk satin fabric in multiple vertical striped colours, commonly used for tunics (kanadir) and underpants (sarāwīl). Also refers to book: Sultani, Traditions Renewed, Changes in women’s traditional dress In the United Arab Emirates during the reign of the late Shaykh Zāyid Bin Sultan āl Nahyān, 1966-2004, By Dr. Reem Tariq

My family arrived in what is now the UAE from Iraq in 1968 when I was around five years old. I think most families who leave their home country and don't ever return are left with a deep longing, of wanting to hold on to their heritage, to who they are through their possessions. My earliest memory, I might have been about four or five, is of colour. Lots of colour; ruby reds, and emerald greens, whether it be found on my mother's fingers or on the rugs, paintings, and tapestries that filled our home. As such, my appetite for all things artistic and beautiful was solidified at home and continued to develop as I grew up.

For my undergraduate degree, I majored in interior design, I continue to practice, through my firm, creating sanctuaries and establishing individual art collections for select clients. For my masters degree, I read Islamic architecture, which led to a survey of the forts and fortifications in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, culminating in the publication of the book Qasr al Husn: An Architectural Survey (1995). This anchored my role in promoting culture and art as I headed the Exhibition & Arts department at the Cultural Foundation Abu Dhabi for over twenty years. For my doctorate, I studied Islamic art and archaeology, continuing this notion of the preservation of tradition and the protection of heritage.

The subjects I chose to pursue consciously or unconsciously drew from my life in the UAE, and the blessing it has bestowed on me. My experience of wearing UAE clothing as I grew up in the community here played a role in my decision to research the topic of dress and its evolution in the UAE. So I began gathering the UAE collection, which I dubbed Sultani

Sulṭānī: (Arabic: sultān: king). In the UAE the term denotes to silk satin fabric in multiple vertical striped colours, commonly used for tunics (kanadir) and underpants (sarāwīl). Also refers to book: Sultani, Traditions Renewed, Changes in women’s traditional dress In the United Arab Emirates during the reign of the late Shaykh Zāyid Bin Sultan āl Nahyān, 1966-2004, By Dr. Reem Tariq