Fit for a Queen: The Clothing of Cleopatra Selene, Egyptian Princess, Roman Prisoner, and African Queen

Cleopatra VII, a figure immortalised by Shakespeare's pen, Hollywood's glitz, and the centre of recent controversies, is a titan in the annals of history. Yet it's her daughter, Cleopatra Selene, who offers a tale of resilience and survival. She held the helm of Mauretania for over two decades, demonstrating strength, leadership, and adaptability. Dr. Jane Draycott, an acclaimed historian and author of "Cleopatra’s Daughter: Egyptian Princess, Roman Prisoner, African Queen", invites us into the world of this lesser-known queen, showcasing her life stages, her evolving attire, and the powerful symbolism behind it. Get ready to delve into a story that's as captivating as it is enlightening. Who was Cleopatra Selene? Cleopatra Selene (circa 40-5 BCE) was the daughter of Cleopatra VII, Queen of Egypt, and Marcus Antonius (better known today as Marc Antony), the Roman consul and triumvir. At the age of six she was declared Queen of Crete and the Cyrenaica by her father in the Donations of Alexandria in 34 BCE, and she was around ten years old when her parents were famously defeated by Octavian at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE and Egypt was conquered and annexed by the Roman Empire. Her life can be divided into three distinct stages: Egyptian princess, Roman prisoner, and African queen. Each stage would have required different types of dress, influenced by the culture and customs of the time. Clothing during her childhood in Alexandria During her childhood in Alexandria, Cleopatra Selene would have worn either Greek or Egyptian dress as the occasion called for it. In Greek dress, she would have worn a chiton, a type of tunic made from a single piece of fabric that was draped and pinned around the body. In Egyptian dress, she might have worn a kalasiris, a close-fitting linen garment adorned with jewellery and embellishments. In portraits of her from this period, we can see that she arranged her hair in a similar style to her mother’s famous ‘melon coiffeur’, topped with a diadem indicating her royal status (Figure 1, Figure 2). Clothing during her time as a Roman prisoner Cleopatra Selene was around ten years old when her parents were defeated by Octavian at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE and Egypt was conquered and annexed by the Roman Empire in 30 BCE. Following her parents’ suicides, she was taken back to Rome by her parents’ enemy Octavian. There is one specific historical occasion upon which we know exactly what she wore: when she and her fraternal twin brother Alexander Helios were paraded through the streets of Rome, exhibited alongside an effigy of their deceased mother in Octavian’s Triple Triumph in 29 BCE, they were dressed as a matching pair, as the Moon and the Sun in reference to their second names, references to the goddess of the moon Selene and the god of the sun Helios. Cleopatra Selene spent the remainder of her childhood as an erstwhile prisoner in his household on the Palatine Hill in the heart of the city. While living as a prisoner in Rome, Cleopatra Selene would have adopted Roman dress to conform to her new environment. As a child, she would have worn the toga praetexta, a garment reserved for children and magistrates, which featured a purple border to signify her noble status. Her hair would have been worn long and loose. She married Juba, the son of the deposed King Juba of Numidia, when she was about fifteen in around 25 BCE. At that stage, Cleopatra Selene would have dressed as a respectable matrona (a married woman) in a stola (a long, sleeveless tunic), a palla (a large rectangular shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. ), and her hair would have been tied back and arranged neatly under a veil. After their marriage, Octavian, now the first Roman Emperor Augustus, sent the couple to Mauretania (modern-day Morocco and Algeria) to rule as King and Queen of a Roman client kingdom.

Figure 1 – Cleopatra Selene (left) as a child with her twin brother Alexander Helios.

Figure 2: Cleopatra Selene as an adolescent.

Figure 3: Cleopatra Selene as an adult.

Figure 4: Cleopatra Selene as an adult.

Figure 5: Cleopatra Selene and her son on the Ara Pacis Augustae.

Figure 6: Cleopatra Selene as an African queen.

Figure 7: Cleopatra Selene as an African queen.

As queen, Cleopatra Selene would undoubtedly have worn clothing dyed purple.

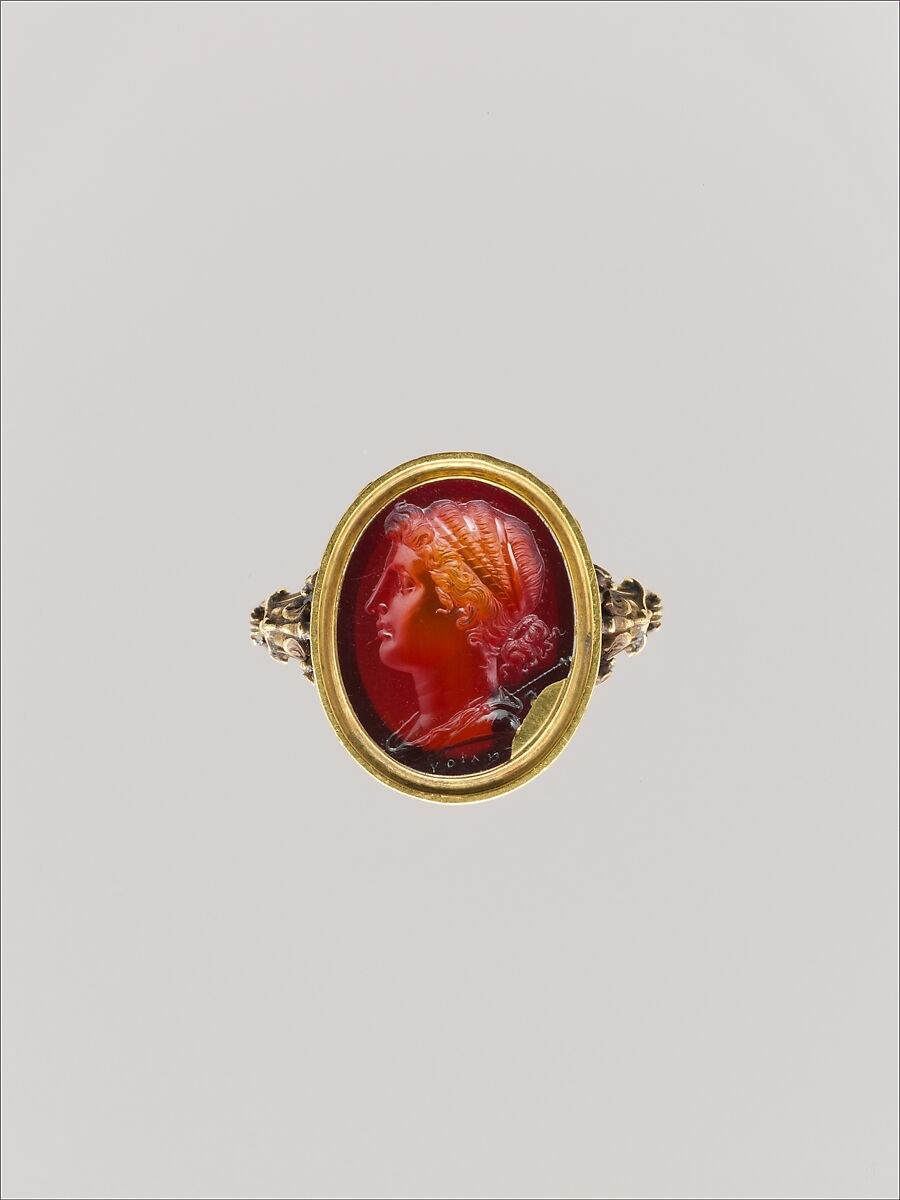

Figure 8: Cleopatra Selene carved by Gnaios.

Share

Tags

Related Post