If you would have travelled to Egypt in the 19

th century, the view of women on the streets of Cairo would have been very different from the view of women in our times. The dress code of a hundred years ago was very different from what it is today. One of these differences would have been one particular costume jewellery item: the Arūsat al Burqa worn on the face veil. In this post, we look at this small piece of adornment, the pace and ways in which traditions change, and the rise of feminism in Egypt.

Veil Decoration and Costume Ornament

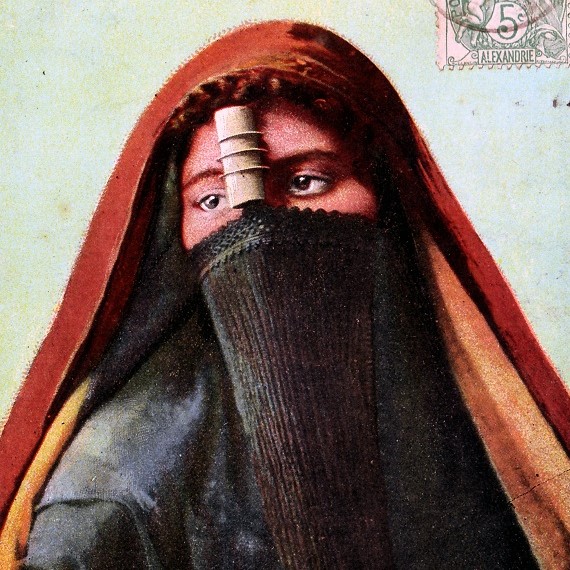

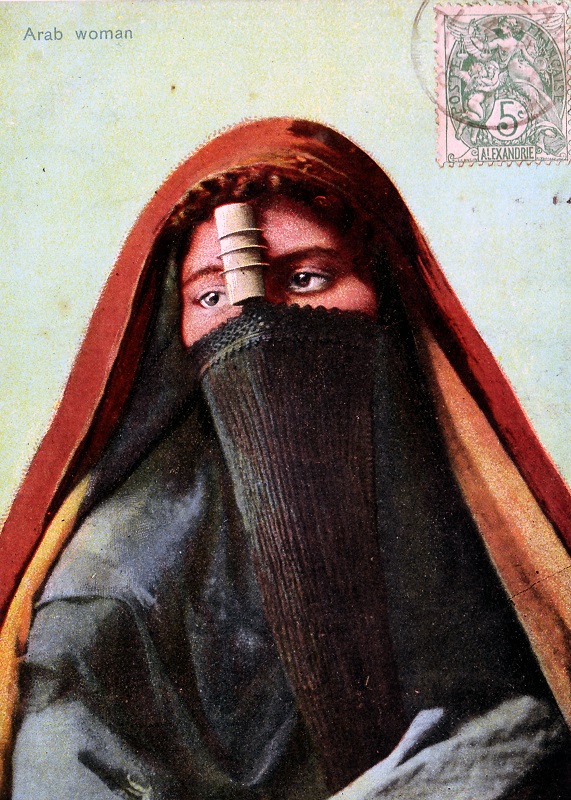

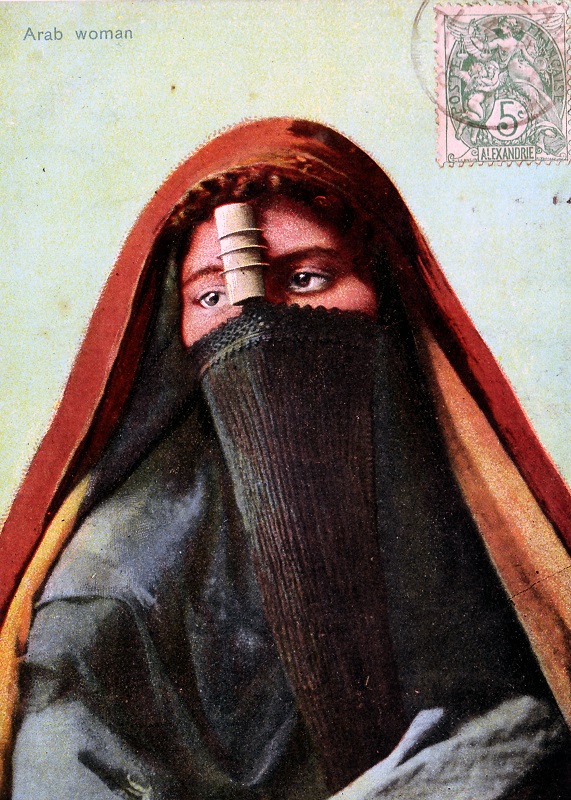

The

Arūsat al Burqa can only rarely be found today in the shop windows of Cairo’s medieval market, Khan el-Khalili, as an icon of another time. In photographs from the early 20

th century, it can still be seen glittering on the foreheads of respectable Egyptian ladies. It is a large, sometimes out of proportion, cylindrical object resting on the nose bridge and the forehead of a woman wearing a face veil. The size of these objects varied, they could range from only a few centimetres to almost ten centimetres in length and half a centimetre to almost three centimetres in diameter.

Arūsat al Burqa means the ‘bride (or doll) of the veil’. The name may also be more loosely translated as ‘pride’ or ‘beauty’, indicating that the object was the only decorative element of the otherwise plain traditional Cairene veil. Another name by which the objects sometimes go is

bark.

Brass and Gold

The

Arūsat al Burqa is not a very heavy object. It is made only of sheet metal and thin subtly twisted wire. Different kinds of metal were often used for this object, including silver, copper, brass, or even iron. Simpler

Arūsat al Burqas were said to have been made merely of a reed tube. But

Arūsat al Burqas were ideally made of plated gold, displaying the wealth of the owner’s family.

The face veils they decorate were made of black crinkly silk, lace, or crocheted cloth, produced in Mahallah Al Kubrah now located in the city of Cairo. The veils were even called

meshakhla or ‘flirtatious’ because of the light mesh that they were made of. So, the

Arūsat al Burqa functioned to brighten up the plain black face veils, and at the same time divert the attention away from what was concealed underneath, away from the eyes of the wearer.

Wire on a Spool

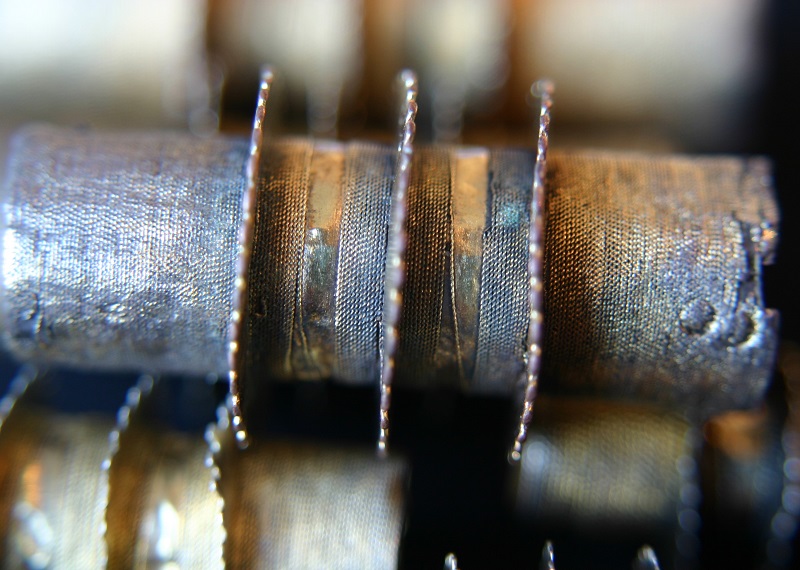

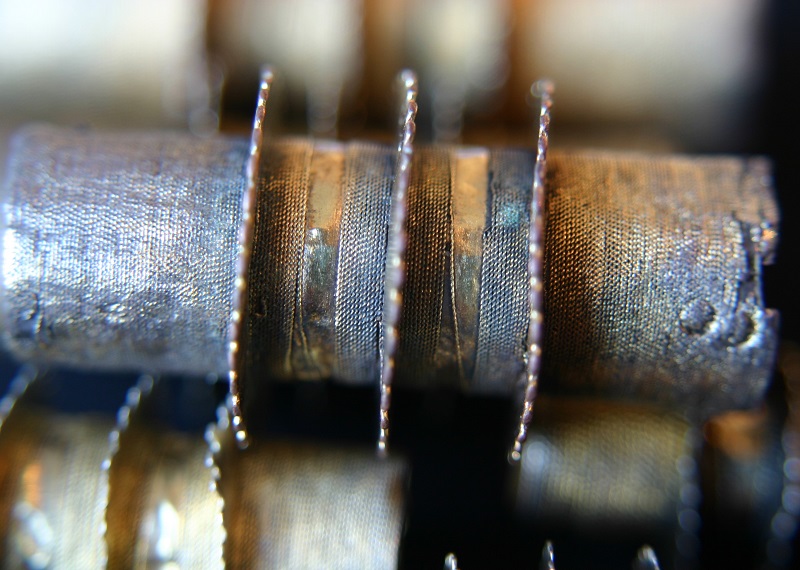

The

Arūsat al Burqa is not a very straightforward object, but it is uniform in its appearance. Every

Arūsat al Burqa consists of several – more or less consistent – parts. The core is a metal cylinder, often constructed around a wooden or reed tube. It is said that sometimes a piece of paper or papyrus scroll on which Quran verses were written, was inserted into the reed as well. The exterior of the reed tube was covered with sheet metal and the seam where the plate closed often remained visible. In the centre of the piece, three circular and serrated metal roundels were attached to the metal tube.

Over all of this, one long piece of twined metal wire was tightly wound, resembling string wound around a spool. The wire also covered the three circular roundels in the centre, running between the teeth of the roundels and continuing on its other side. On the two spaces between the roundels, the encircling wire was often left open and the metal sheet was deliberately left visible. This must have subtly and attractively reflected the light of Egypt’s sun. In some instances, no metal wire was used, but impressions on the metal surface imitated the thread.

Image credit: Auckland War Memorial Museum, New Zealand. Creative Commons

Keeping the Veil in Place

It is said that the

Arūsat al Burqa was worn to hold the thin thread of the face veil which passed over the nose and forehead of the wearer, in place. The

Arūsat al Burqa may have been used in conjunction with the more common band that went around the forehead to fix the veil over the nose and hold it in place.

In the traditional Cairene veil, the band was tied far back on the woman’s head and was often made of a fringed or otherwise decorated textile. However, the

Arūsat al Burqa was an amulet as well, protecting the wearer from harm. With its shimmering metal, it may have warded off evil spirits or kept the influence of the Evil Eye at bay. But whatever the main function, the

Arūsat al Burqa was an essential part of the Egyptian costume for a long time.

The search for the Arūsat al Burqa

Not much has been written on

Arūsat al Burqa. While I was conducting my research in the early 2000s, a jeweller in the Khan el Khalili asked me if I would like to see more examples, however, it took months before he found a second one. Although

Arūsat al Burqas were available on the antique market after that for about ten years, they have now almost completely disappeared again. From old photographs, Orientalist paintings from the 19

th and 20

th centuries, drawings, and descriptions by early Nile travellers, as well as from the jewellers' stamps on the objects themselves, we can determine that the period in which the

Arūsat al Burqas were used roughly covers at least the last two centuries. Of course, there may be evidence from earlier periods as well, although this could not be attested thus far.

Tribute to an amulet

At the turn of the last century, the use of the

Arūsat al Burqa still expressed the wealth and social position of its owner. Nevertheless, it would take only a few years for the object to slide almost into oblivion. Soon after this, high-status women began to wear the Turkish veil (the

yashmak

Yashmak: (Old Turkic yaş – to hide), a traditional face veil commonly used by women in the Turkmen and other Turkic society. It has different variants depending upon its geographical locations ranging from a thick veil made of horse to a thin lace veil covering the face with slits for the eyes. ) without the object. In the first decades of the 20

th century, many political changes took place in Egypt and with it, the

meshakhla and its

Arūsat al Burqa disappeared from the scene almost completely.

With the beginning of the women’s movement in Egypt, the use of the

Arūsat al Burqa was completely abandoned. What was once made by master jewellers such as Aziz Rizq, was soon forgotten. Sixty years later, the objects themselves are very hard to come by. Obtaining depictions of Arūsat al Burqas

more recent than from the turn of the 20

th century has proved even more difficult than obtaining the antique objects themselves.

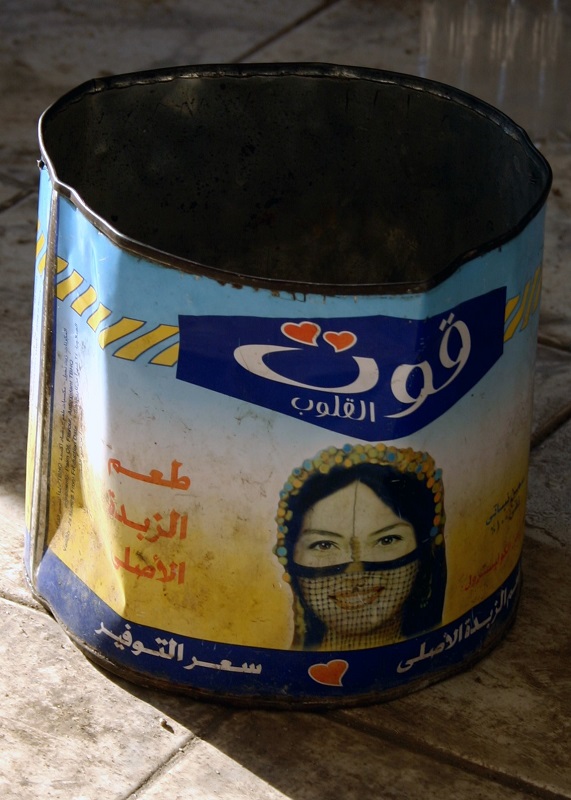

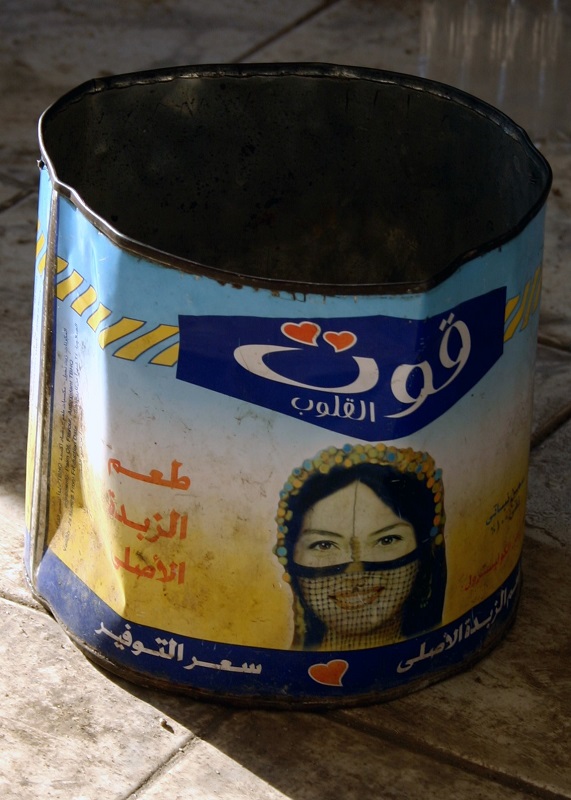

The one depicted on the exterior of a can (bought around the turn of thís century) once containing cooking products is, however, remarkable. The image is used to market the quality and traditional values of household products, which is an interesting use of the values the

Arūsat al Burqa once stood for. It certainly is a testimony that, although this piece of costume jewellery is no longer worn, what it once stood for has not been erased from the Egyptian collective memory just yet.

Further Reading

- Bos, J. E. M. F. (forthcoming) Making Sense of the Veil: Traditional face veils from the Asian and North African region.

- Bos, J. E. M. F. (2016) Egypt’s Wearable Heritage.

- Bos, J. E. M. F. (2006) "Arousa el Burqa, The pride of veiling in Egypt and North East Africa." Ornament 29(2): 60-63.

- Fahmy, A. (2007) Enchanted Jewelry of Egypt: The Traditional Art and Craft of Caïro.

About the Author

Jolanda E.M.F. Bos is an archaeologist and dress anthropologist. Her research fields comprise

archaeological beadwork analysis, contemporary costume, personal adornment (as the combination of dress, body decoration, veils, jewellery and amulets) and the social implications of dress.Over the last twenty years Jolanda has been working at several excavations in Egypt (at the moment at Tell el Amarna, Egypt) and the Netherlands, as well as on museum exhibits both in the Netherlands and in Egypt. At present, she studies ancient Egyptian hairstyles from Tell el-Amarna at the University of Leiden (the Netherlands) as part of her PhD research.

Jolanda is the author of several articles and books (i.e., ‘Paint it, Black’ and ‘Egypt’s Wearable Heritage’), and regularly lectures on the subject. She is also the driving force behind the

Wearable Heritage website. Wearable Heritage is also on

Instagram account and

Facebook.

Other blog posts by Jolanda Bos:

Read a review of her book

Egypt's Wearable Heritage here.

*Copyright to all images belongs to Jolanda Bos. Used with permission.