Object NotePart of an ensemble containing a pair of matching trousers also in the collection (

ZI2021.500912a ASIA).

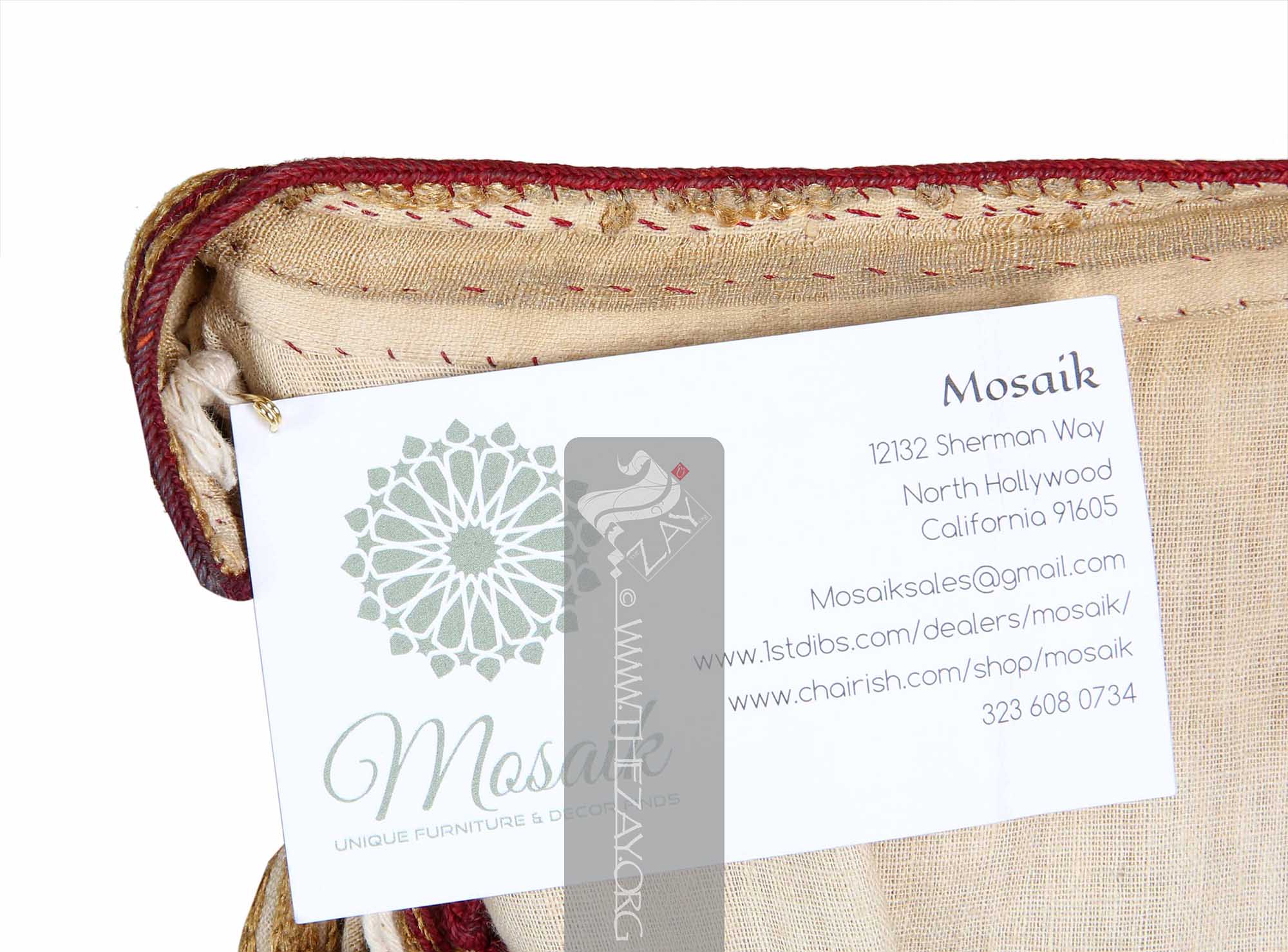

Object History This piece of garment was purchased by

Dr. Reem Tariq

Ṭariq: (Arabic; Synonym: tulle_bi_talli

Tūlle_bi_tallī: (French: Tulle – a city in France where fine material for veil was first made; Turkish: tel – wire; Synonym: tariq; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the North African Arab region specifically in Egypt.

; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the Levant Arab region specifically in Lebanon.

El Mutwalli

Dr. Reem Tariq

Ṭariq: (Arabic; Synonym: tulle_bi_talli

Tūlle_bi_tallī: (French: Tulle – a city in France where fine material for veil was first made; Turkish: tel – wire; Synonym: tariq; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the North African Arab region specifically in Egypt.

; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the Levant Arab region specifically in Lebanon.

el Mutwallī: Founder (CEO) of the Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative, a public figure, speaker and author. An expert curator and consultant in Islamic art and architecture, interior design, historic costume, and UAE heritage. from Mosaik, an independent antique dealer in California, in 2018 to add to and enhance The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative Collection.

It originally belonged to Föhret Aydin, a lady from the town of Sandilik in the province of Afyonkarahisar, and was later inherited by her daughter Latife Aydin. She eventually passed it to her grandchild Balk Aydin a management consultant from New York born in Bursa, Türkiye, before being acquired by Mosaik, and eventually ending up in the collections of The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative.

Object Features This is an ivory jacket (

entari

: (Turkish; Synonym: Antari), a traditional Turkish long jacket-like unisex garment worn during the Ottoman era. It often featured an open front with long sleeves and was worn over an undershirt and a pair of trousers and was sometimes layered by a short waist or hip-length jacket. ) possibly made from a blend of silk and wool, with long sleeves and a short collar. The piece is a front-open garment without any fastening. It is embellished with embroidered patterns, and trimmings along its hems, cuffs, and neckline.

The field of the

entari

: (Turkish; Synonym: Antari), a traditional Turkish long jacket-like unisex garment worn during the Ottoman era. It often featured an open front with long sleeves and was worn over an undershirt and a pair of trousers and was sometimes layered by a short waist or hip-length jacket. is embellished with (

chain_stitch

Chain_stitch: An embroidery technique where a looped stitch is made in a continuous chain-like pattern. Each stitch is formed by looping the thread through the previous stitch, creating a linked chain. ) style embroidered floral and geometric patterns running in vertical panels. It is hand embroidered using golden-coloured silk

floss

Floss: (Old French: flosche – nap of velvet), is a type of silk fibre obtained from the cocoons of wild silkworms. It is characterized by its long, fluffy fibers that are not tightly woven, making it ideal for use in various textile applications such as embroidery, lace-making, and sewing. thread. A thick panel featuring repeats of star-shaped floral motif is alternated with a narrower panel featuring repeats of a leaf and knot motif arranged in a chain-like fashion.

The garment has two long slits on the sides with a pocket at the end of each which divides the skirt into three segments, thus making it an (üçetek_entari). A red silk braided trimming is (

appliqued

Appliqued: (French: appliquer – Apply), ornamental needlework where small pieces of decorative fabric are sewn on to a larger piece to form a pattern.) to the scalloped hem and edges with extended corners featuring floral shapes and motifs. Similar trimming is used for the cuffs, as well as the deep scalloped neckline.

A unique feature of this

entari

: (Turkish; Synonym: Antari), a traditional Turkish long jacket-like unisex garment worn during the Ottoman era. It often featured an open front with long sleeves and was worn over an undershirt and a pair of trousers and was sometimes layered by a short waist or hip-length jacket. is its cuffs which, unlike its contemporaries, are tapered and pleated instead of featuring long

cutwork

Cutwork: It is a surface embroidery technique using two main stitches – the running stitch and the buttonhole stitch and is usually made on fine linen or cotton with threads that match the fabric colour. It creates a lace like pattern while the stitches prevent the fabric from fraying. edges. The entire piece is hand stitched, hand embroidered, and is primarily lined with fine ivory cotton, except for the cuffs which are lined with chequered woven cotton in a range of colours – blue, black, lavender, and ivory.

By the early 20th century wearing an

entari

: (Turkish; Synonym: Antari), a traditional Turkish long jacket-like unisex garment worn during the Ottoman era. It often featured an open front with long sleeves and was worn over an undershirt and a pair of trousers and was sometimes layered by a short waist or hip-length jacket. especially an üçetek_entari such as it, was mostly limited to ceremonial celebrations such as weddings and henna rituals and they were often kept carefully in boxes.

More InfoPrior to the widespread acceptance of European clothing in the Ottoman Empire, individuals – men and women – residing in urban areas, regardless of their faith or social standing, typically adorned themselves with three primary articles of clothing.

These included a calf-length cotton undershirt or (

gömlek

Gömlek: (Proto-Turkic: köyŋelek – Shirt; Azerbaijani: köynək – Shirt; Turkmen: koynek

Koynek: A traditional long, loose-fitting tunic or dress worn by Turkmen women in Central Asia typically made of silk or cotton, adorned with intricate embroidery, and often characterized by vibrant colours and geometric patterns. It is cultural symbol of significant importance reflecting the artistic heritage of Turkmen people. – long loose tunic dress), a traditional calf-length sleeved undershirt or tunic generally made of a plain white cotton, silk, or linen fabric, some more lightweight than others, worn by both Ottoman men and women of all communities throughout the empire.

), featuring long sleeves, which was worn over a pair of loose trousers known as (

shalvar

shalvār: in Farsi, in the Emirati colloquial: ṣarwāl. In the Levantine colloquial: Shirwāl. Plural: sarāwīl, ṣarāwīl, sharāwīl, ṣarwīlāt). It is loose pants at the waist with folds, and narrow at the ankles. It is tied with a rope at the waist.). Additionally, they would wear a long-sleeved robe called an

entari

: (Turkish; Synonym: Antari), a traditional Turkish long jacket-like unisex garment worn during the Ottoman era. It often featured an open front with long sleeves and was worn over an undershirt and a pair of trousers and was sometimes layered by a short waist or hip-length jacket. , reaching the ankles or floor.

Although,

entari

: (Turkish; Synonym: Antari), a traditional Turkish long jacket-like unisex garment worn during the Ottoman era. It often featured an open front with long sleeves and was worn over an undershirt and a pair of trousers and was sometimes layered by a short waist or hip-length jacket. became more and more ceremonial over the period of time, older üçetek_entari, particularly for travelling served some practical purposes. Wearers would often fold and tuck the front parts into their waistband, thus creating a layering that would not just look good and assist them in moving around but also create two pouches where the wearer could store food and sometimes small stones to use with slingshots against potential attacks on the road.

Additional layers were added as necessary, based on weather conditions, social occasions, and social status. These layers encompassed items such as waistcoats, short jackets like (

cepken

Cepken: (Tartar: çepken – Outerwear; Synonyms: Shepken, Chekman, Chikmyan and other analogues in various Turkic languages with varied interpretations), short waist-length jacket traditionally worn by both Ottoman men and women throughout the empire. It usually featured full sleeves, elaborate embroidery, and a short stiff collar with front fastenings. ) and (

yelek

Yelek: (Old Anatolian: yélek – Vest; Synonyms: Jelick, Jilek), short waist or hip length vest traditionally worn by both Ottoman men and women throughout the empire. Ranging from sleeveless to full sleeves, these vests were usually front open and without any fastenings. Often cepken jackets were used as yelek. ), extra

entari

: (Turkish; Synonym: Antari), a traditional Turkish long jacket-like unisex garment worn during the Ottoman era. It often featured an open front with long sleeves and was worn over an undershirt and a pair of trousers and was sometimes layered by a short waist or hip-length jacket. , as well as coats of various sizes and lengths.

Belts adorned with elaborate embroidery and ornate buckles, or just embroidered sashes (

cummerbund

Cummerbund: (Anglicized from Hindustani: kamarband

kamarband: (Persian: kamarband – a waistband or sash tied around the waist, synonym: cummerbund), a broad sash worn around the waist by men. In the 17th century, the British Indian Army adopted this style from the Indian sepoys and made it a part of the English lexicon. from Persian: kamarband

kamarband: (Persian: kamarband – a waistband or sash tied around the waist, synonym: cummerbund), a broad sash worn around the waist by men. In the 17th century, the British Indian Army adopted this style from the Indian sepoys and made it a part of the English lexicon. – a waistband or sash tied around the waist), a broad sash worn around the waist by men. In the 17th century the British Indian Army adopted this style from the Indian sepoys and made it a part of the English lexicon. ) were utilised to accentuate the bust, waist, and hips, creating a defined silhouette.

At its peak, the Ottoman Empire spanned three continents and served as the crossroads between the East and the West – the Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Eastern Europe including the Balkans till the southern edge of the Great Hungarian Plain, Northern Africa, and Eastern Mediterranean.

After the conquest of the Arab world in c. 1516-1517 CE its control over the Middle East lasted for four centuries until the early 20th century with the onset of WW I and the Arab Revolt. These four hundred years witnessed many instances of mutual Arab and Ottoman cultural influences and exchanges. Through areas such as social life and art – decorative and performing –we come across several instances of Arab and Turkish culture blending together through the centuries.

Just as European fashion was often inspired by the French court this socio-cultural blending between Ottoman Turkey and the Middle East was clearly reflected in its fashion and material culture.

Thus, while emulating Ottoman fashion as the mark of class in the Arab world was one side of the puzzle adapting Eastern European fashion particularly Balkan as part of mainstream couture culture because of the sizable Balkan population within the Empire was another. Therefore, it is not surprising to find several articles of clothing and their terms similar between the two cultures.

Links

- Cangökçe, Hadiye, et al. Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nun Son Döneminden Kadın Giysileri = Women’s Costume of the Late Ottoman Era from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection. Sadberk Hanım Museum, 2010.

- Küçükerman, Önder, and Joyce Matthews. The Industrial Heritage of Costume Design in Turkey. GSD Foreign Trade Co. Inc, 1996.

- AĞAÇ, Saliha, and Serap DENGİN. “The Investigation in Terms of Design Component of Ottoman Women Entari

: (Turkish; Synonym: Antari), a traditional Turkish long jacket-like unisex garment worn during the Ottoman era. It often featured an open front with long sleeves and was worn over an undershirt and a pair of trousers and was sometimes layered by a short waist or hip-length jacket. in 19th Century and Early 20th Century.” International Journal of Science Culture and Sport (IntJSCS), vol. 3, no. 1, Mar. 2015, pp. 113–125. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/91778

- Parker, Julianne. “OTTOMAN AND EUROPEAN INFLUENCE IN THE NINTEENTH-CENTURY BRIDAL COLLECTION OF THE AZEM PALACE, DAMASCUS, SYRIA.” Journal of Undergraduate Research: Brigham Young University, 18 Sept. 2013. http://jur.byu.edu/?p=6014

- Koç, Adem. “The Significance and Compatibility of the Traditional Clothing-Finery Culture of Women in Kutahya in Terms of Sustainability.” Milli Folklor, vol. 12, no. 93, Apr. 2012. 184. https://www.millifolklor.com/PdfViewer.aspx?Sayi=93&Sayfa=181

- Micklewright, Nancy. “Late-Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Wedding Costumes as Indicators of Social Change.” Muqarnas, vol. 6, 1989, pp. 161–74. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1602288. Accessed 13 July 2023.

- Micklewright, Nancy. “Looking at the Pst: Nineteenth-Century Images of Constantinople and Historic Documents.” Expedition, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 24–32. https://www.penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/pdfs/32-1/micklewright.pdf

- Ozgen, Ozlen, et al. “Henna Ritual Clothing in Anatolia from Past to Present: An Evaluation on Bindalli.” Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, 2021, https://doi.org/10.32873/unl.dc.tsasp.0122.

- Denny, Walter B., and Sumru Belger Krody. The Sultan’s Garden: The Blossoming of Ottoman Art. The Textile Museum, 2012. https://museum.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaxdzs3226/f/Sultans%20Garden%20Catalogue.pdf

- Ersoy, Ayla. Traditional Turkish Arts. Ministry of Culture and Tourism Publications, 2008. https://teda.ktb.gov.tr/Eklenti/6593,traditionalturkishartspdf.pdf?0

- https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/451160

- https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O90892/entari

: (Turkish; Synonym: Antari), a traditional Turkish long jacket-like unisex garment worn during the Ottoman era. It often featured an open front with long sleeves and was worn over an undershirt and a pair of trousers and was sometimes layered by a short waist or hip-length jacket. -unknown/

- https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/85546

- https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/85540

- https://islamicart.museumwnf.org

- https://www-kutahya-gov-tr.translate.goog/geleneksel-giysi

- https://archive.aramcoworld.com/issue/200703/the.skill.of.the.two.hands.htm

- http://www.turkishculture.org/textile-arts/clothing/womens-garments/womens-garments

- http://jezebeljane.blogspot.com/2015/09/womens-clothing-in-16th-century-turkey

- https://www.issendai.com/16thcenturyistanbul/visual-dictionary/kaftan/

- https://babogenglish.wordpress.com/2016/02/25/turkey-general-information/

- https://ertugrulforever.com/turkish-fashion-2021/

- https://northamericaten.com/turkish-clothing-of-ottoman-times/

- https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2019/04/turkish-traditional-costumes-from-head-to-toe