As part of our webinar series, Dialogues on the Art of Arab Fashion, our guest, auctioneer Kerry Taylor talked to Dr Reem el Mutwalli about the history and development of the Kashmir shawl.

Kerry Taylor

Kerry Taylor started her career at Sotheby’s Chester where she became the youngest auctioneer in the company’s history and a director at the age of 21. She then moved to Sotheby’s London where she re-established auctions of costume and textiles at the New Bond Street salesroom. Here she was responsible for numerous high-profile sales including the wardrobes of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Dame Barbara Cartland, Dame Joan Sutherland, Maria Callas and others.

She ventured out on her own, establishing Kerry Taylor Auctions in 2003, specializing in both vintage and contemporary fashion, costume, as well as European, Asian and Islamic textiles. Kerry is a member of The Zay Initiative’s advisory circle.

The history and origin of the Kashmir shawl

It all starts with a very special goat known as the Changhthangi goat, a breed that is native to the Himalayan regions of Ladakh and Kashmir in northern India. The goats’ thick undercoat grown during the colder months is harvest during Spring. This extremely fine wool, known as cashmere or pashmina wool, is then spun and woven to produce Kashmir shawls.

The oldest known Kashmir shawl dates to the 17th century. Historically it is an extremely rare and expensive item. It can take up to 18 months to create a single shawl. In Kashmir, it was regarded as a status symbol and only worn by men of high standing.

The teardrop shape usually associated with a Kashmir shawl, later known as the paisley, is known in India and Persia as the boteh or buta, a Persian word meaning bush, cluster of leaves, or flower bud.

The cypress tree, a Zoroastrian symbol of life, symbolising eternity, strength, integrity and freedom. After the Islamic conquest of Persia in the 7th century, Zoroastrian people migrated to India and Kashmir where they continued to depict their beloved cypress tree, but now with a bent-over top. This symbol became known as a boteh, meaning shrub, bush, or bent tree. It was a symbol of the duress and hardship of the people, but also their strength and resilience. They will bend but they will not break.

Captain John Foote of the Hon. East India Company, painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1761. The outfit depicted in the portrait as it appears in the collection of the York Museums, UK

Kashmir shawls in Europe

Kashmir shawls were first introduced to the West via the sea trading routes between Europe and Asia. A painting of Captain John Foote of the Hon. East India Company (1761) by Sir Joshua Reynolds is the earliest visual record of a Kashmir shawl worn by a European. In this case, it was still worn by a man in the same manner as it was used in India – tied as a sash not used as a shawl. It only became popular as a women’s accessory later.

In the late 1700s, Empress Josephine, wife of Napoleon Bonaparte became famous for her collection of Kashmir shawls. She owned hundreds, mostly gifted to her by her husband, and are often credited for popularising the Kashmir shawl as a women’s accessory in European fashion circles. It was still a very expensive item and only worn by the elite.

Kashmir shawls produced in Europa

European demand became so great that the producers in India and Kashmir could not keep up. Textile mills in France, Holland and Britain began producing shawls. They could however not recreate the colour richness of the authentic Kashmir products and the locally produced designs were far less opulent than the imported ones.

The textile mill in Paisley, Scotland became one of the major producers of these shawls and the British began referring to these distinct boteh designs as paisley. In France, it was referred to as palme, and in the Netherlands as bota. The paisley shawl became a must-have accessory and a status symbol worn to important events and celebrations and was often depicted in portraits of important people. These portraits later became a valuable resource in documenting the development of the paisley pattern and the variations occurring in different times and geographical locations.

Where, at first, shawls were woven in one piece, later designs were woven as separate strips or squares which was then sewn together by highly skilled sewers. This was to speed up production, to include more complicated designs, and to create bigger shawls not limited by the size of the loom.

Even though these shawls became more common and accessible to the masses, the quality was still good and some of the earlier European-produced shawls are now highly sought-after collectors’ items.

Kashmir shawls in Arabia

Among the Bedouins of the Arabian Peninsula, the Kashmir shawls were worn by men as a headdress known as a Tarma Shawl. It was larger than the normal white headdress, heavily decorated and with a fringed edge. It was usually only worn by royalty and the elite. Although it is still used today, it is scarce and only worn by older men on cold winter days.

Bedouin men also wear a Dglah (from Hindi word Dagla) a full-length jacket or coat often decorated with the boteh design.

It is unclear whether the Kashmir shawl was originally introduced to Arabia via Europe or directly from India. Although Kashmir or pashmina shawls are a common sight in malls and shops in Arab countries today, it was never traditionally worn by Arab women.

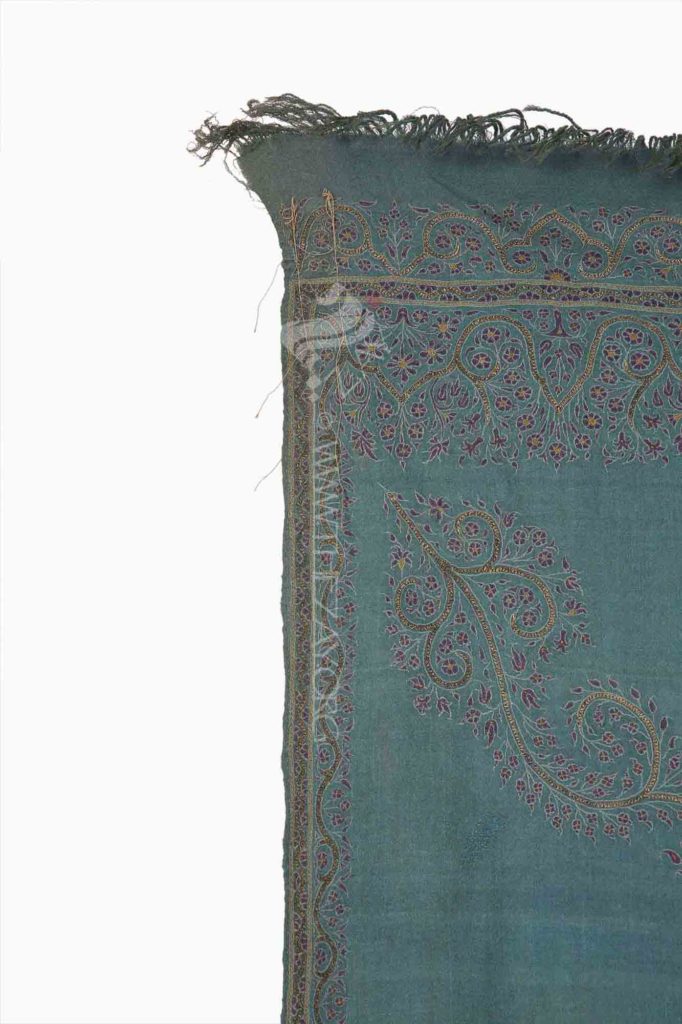

Kashmir shawls in The Zay Collection

The Zay Collection includes several Kashmir shawls, some of these were purchased on auction from Kerry Taylor Auctions from the collection of Dr Joan Coleman.

The Kashmir shawl is an example of how the combination of high-quality natural fibres and fine craftsmanship can create a superior product that is exclusive to a specific region of the world. Yet, when taken into, and adopted by other cultures it will adapt, change, and be reinvented into different styles and fashions particular to that part of the world. And so it will become a thread that connects, across cultures and across time.

Understanding other cultures, traditions, fashions, and way of dress becomes a way to understand each other. This is why The Zay Initiative started this Dialogue on the Art of Arab fashion and why we invite you to join the conversation. More information on our other conversation and upcoming events can be found here.