Object History This piece of garment was purchased by

Dr. Reem Tariq

Ṭariq: (Arabic; Synonym: tulle_bi_talli

Tūlle_bi_tallī: (French: Tulle – a city in France where fine material for veil was first made; Turkish: tel – wire; Synonym: tariq; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the North African Arab region specifically in Egypt.

; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the Levant Arab region specifically in Lebanon.

El Mutwalli

Dr. Reem Tariq

Ṭariq: (Arabic; Synonym: tulle_bi_talli

Tūlle_bi_tallī: (French: Tulle – a city in France where fine material for veil was first made; Turkish: tel – wire; Synonym: tariq; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the North African Arab region specifically in Egypt.

; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the Levant Arab region specifically in Lebanon.

el Mutwallī: Founder (CEO) of the Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative, a public figure, speaker and author. An expert curator and consultant in Islamic art and architecture, interior design, historic costume, and UAE heritage. as a set of ensembles from an independent dealer in London in 2021 to add to and enhance The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative Collection.

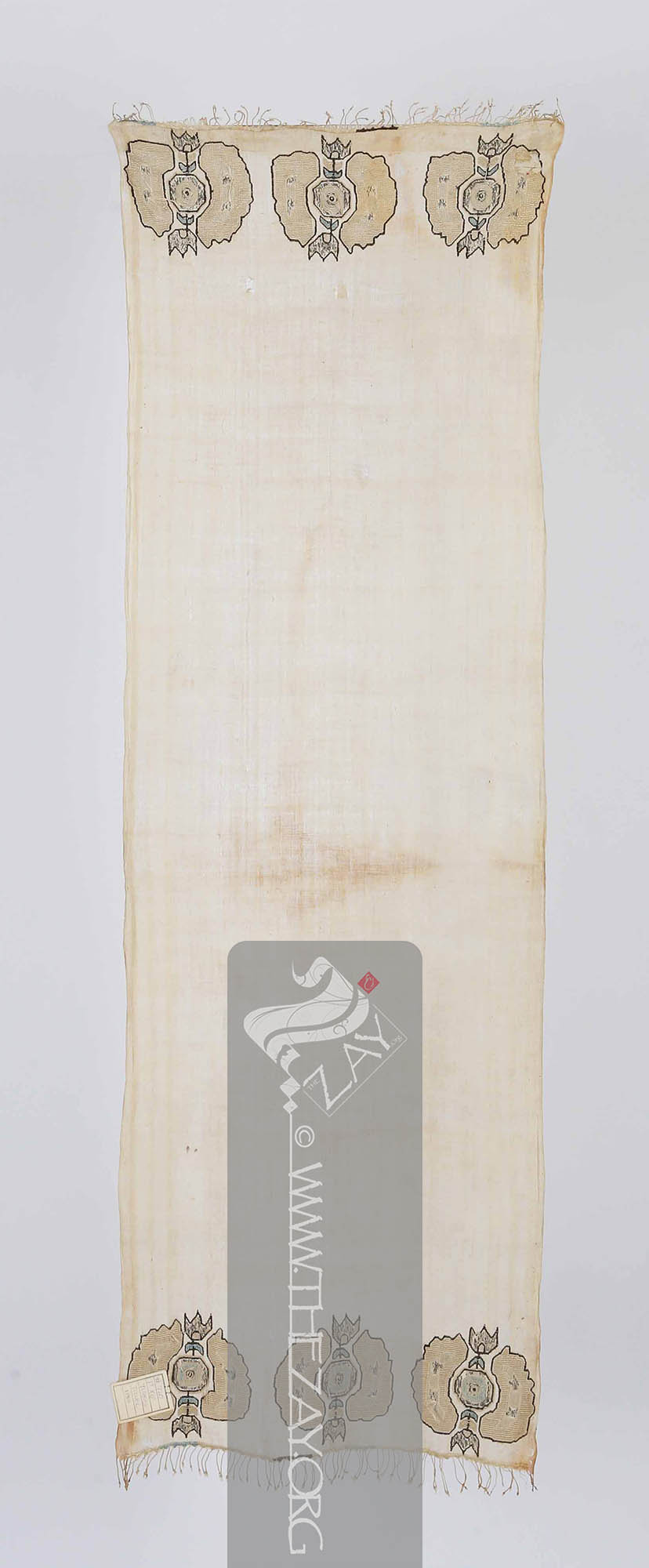

Object Features This is a rectangular ivory towel (

yaglik

Yaglik: (Proto Turkic: yaglik – kerchief, head scarf), an embroidered textile, traditionally rectangular in shape, used for household decoration or special occasions. Originally referring to napkins made of cotton or linen, it evolved to include ornate embroidery, particularly favoured by young brides in their trousseau. ) in cotton (

gauze

Gauze: (English), very fine wire mesh transparent fabric of silk, linen, or cotton.) with embroidered embellishment and fringed (

warp

Warp: One of the two basic components used in weaving which transforms thread or yarns to a piece of fabric. The warp is the set of yarns stretched longitudinally in place on a loom before the weft

Weft: one of the two basic components used in weaving that transforms thread or yarns into a piece of fabric. It is the crosswise thread on a loom that is passed over and under the warp threads. is introduced during the weaving process. ) ends.

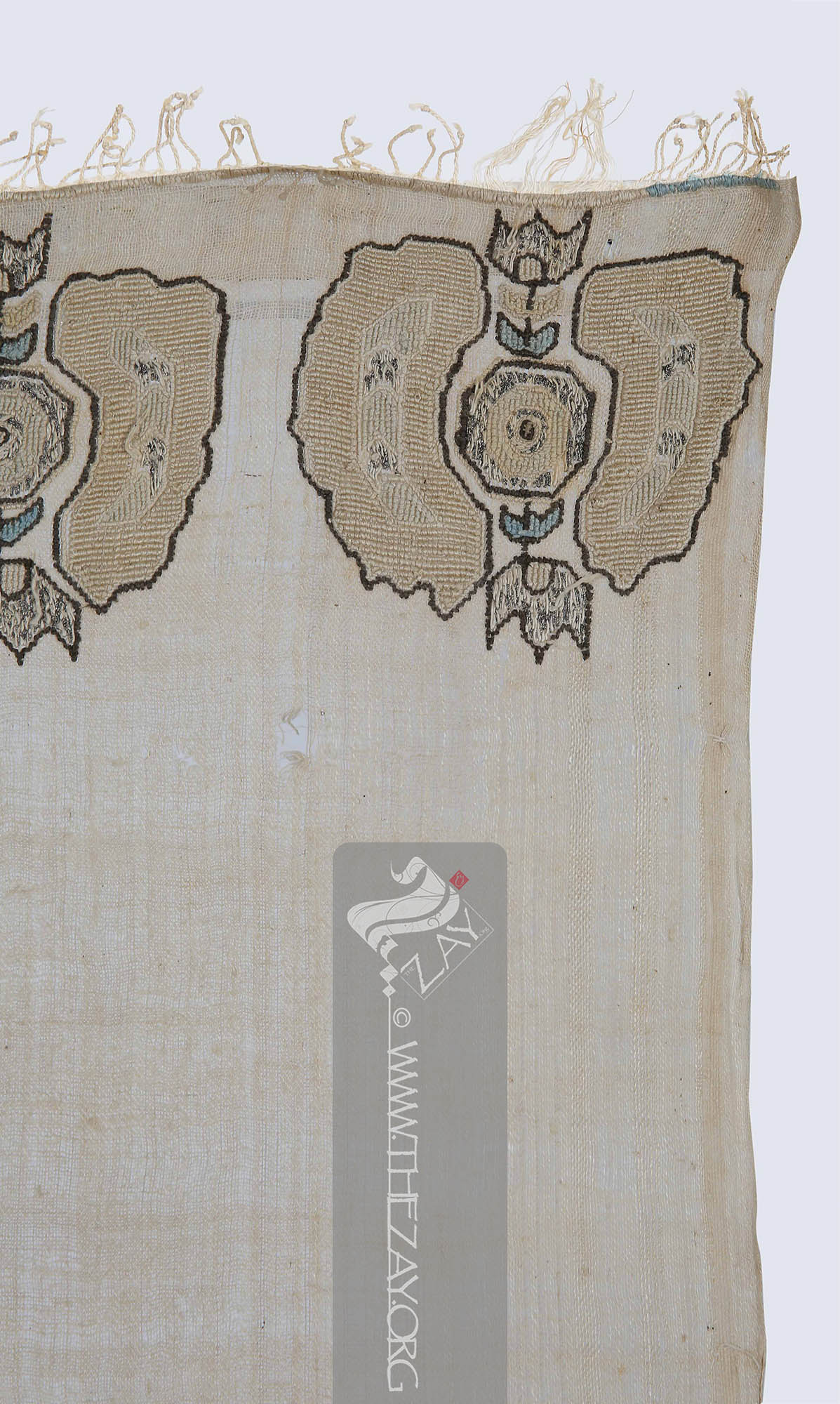

The field of the piece is plain however, repeats of large pomegranate motifs embroidered with ivory, blue, and brown silk

floss

Floss: (Old French: flosche – nap of velvet), is a type of silk fibre obtained from the cocoons of wild silkworms. It is characterized by its long, fluffy fibers that are not tightly woven, making it ideal for use in various textile applications such as embroidery, lace-making, and sewing. threads with metal wire – silver – highlights embellish the edges as borders.

The design is double-sided, so the

yaglik

Yaglik: (Proto Turkic: yaglik – kerchief, head scarf), an embroidered textile, traditionally rectangular in shape, used for household decoration or special occasions. Originally referring to napkins made of cotton or linen, it evolved to include ornate embroidery, particularly favoured by young brides in their trousseau. features no top or underside. The fabric itself is a (

selvedge

Selvedge: (English: Self-finished edge or self-edge: a dialect forming transition), an edge produced on woven fabric during manufacture that prevents it from unravelling. Traditionally the term selvage applied to only loom woven fabric, presently it could be applied to flat knitted fabric too. ) to

selvedge

Selvedge: (English: Self-finished edge or self-edge: a dialect forming transition), an edge produced on woven fabric during manufacture that prevents it from unravelling. Traditionally the term selvage applied to only loom woven fabric, presently it could be applied to flat knitted fabric too. weave but the

warp

Warp: One of the two basic components used in weaving which transforms thread or yarns to a piece of fabric. The warp is the set of yarns stretched longitudinally in place on a loom before the weft

Weft: one of the two basic components used in weaving that transforms thread or yarns into a piece of fabric. It is the crosswise thread on a loom that is passed over and under the warp threads. is introduced during the weaving process. ends are hemmed with ivory and touches of blue and brown silk

floss

Floss: (Old French: flosche – nap of velvet), is a type of silk fibre obtained from the cocoons of wild silkworms. It is characterized by its long, fluffy fibers that are not tightly woven, making it ideal for use in various textile applications such as embroidery, lace-making, and sewing. beyond which the remaining cotton threads are braided and corded in a series of fringes.

During the late Ottoman period, especially from c. 18th century, such elaborately done

yaglik

Yaglik: (Proto Turkic: yaglik – kerchief, head scarf), an embroidered textile, traditionally rectangular in shape, used for household decoration or special occasions. Originally referring to napkins made of cotton or linen, it evolved to include ornate embroidery, particularly favoured by young brides in their trousseau. would often be used as a waist band (

kusak

Kusak: (Turkish), a wide belt, sash or girdle worn around the waist to secure clothing. Typically made of fabric, leather, or embroidered material, it serves both practical and decorative purposes by adding a touch of elegance to traditional Ottoman attire. ) too, over a pair of loose trousers (

shalvar

shalvār: in Farsi, in the Emirati colloquial: ṣarwāl. In the Levantine colloquial: Shirwāl. Plural: sarāwīl, ṣarāwīl, sharāwīl, ṣarwīlāt). It is loose pants at the waist with folds, and narrow at the ankles. It is tied with a rope at the waist.) and undershirt (

gömlek

Gömlek: (Proto-Turkic: köyŋelek – Shirt; Azerbaijani: köynək – Shirt; Turkmen: koynek

Koynek: A traditional long, loose-fitting tunic or dress worn by Turkmen women in Central Asia typically made of silk or cotton, adorned with intricate embroidery, and often characterized by vibrant colours and geometric patterns. It is cultural symbol of significant importance reflecting the artistic heritage of Turkmen people. – long loose tunic dress), a traditional calf-length sleeved undershirt or tunic generally made of a plain white cotton, silk, or linen fabric, some more lightweight than others, worn by both Ottoman men and women of all communities throughout the empire.

) and a waist-length jacket (

cepken

Cepken: (Tartar: çepken – Outerwear; Synonyms: Shepken, Chekman, Chikmyan and other analogues in various Turkic languages with varied interpretations), short waist-length jacket traditionally worn by both Ottoman men and women throughout the empire. It usually featured full sleeves, elaborate embroidery, and a short stiff collar with front fastenings. ).

The symbolism of pomegranate too is an interesting aspect. The cultural significance of the fruit around the world is undeniable. However, in the Middle, Near East, and the Mediterranean, the significance of the pomegranate is steeped in tradition and faith and has both positive and negative connotations.

According to some scholars of the Abrahamic faith the expulsion of Adam and Eve may have been because of a pomegranate and not an apple just like the fall of Persephone that led her to Hades in Greek and Roman myths. Having said that, the pomegranate is also the promised fruit of Paradise both in Christianity and Islam, thus becoming both the promised as well as the forbidden fruit.

The red arils of the pomegranate have been used as a symbol to represent blood over centuries in many cultures, which led the ancient Persians to use it on their shields as signs of protection and later came to symbolise the blood of Christ and his suffering – Passion of Christ – by the Christians. A fairly drought-resistant in nature, this fruit-bearing plant can also be categorized as the Biblical ‘Tree of Life’.

However, its symbolic significance in the Near and the Middle East stretches far beyond the advent of monotheism. Just like in the Greek and Roman myths, the pomegranate has played an important role in the myths and legends of the pre-monotheistic faiths in the region, the significance of which has been later adopted by the Judeo-Christian faiths and beliefs. Even today it is a common symbol of fertility during wedding rituals amongst many cultures across the world especially in the Middle and Near East.

More InfoIn Turkish parlance, the term

yaglik

Yaglik: (Proto Turkic: yaglik – kerchief, head scarf), an embroidered textile, traditionally rectangular in shape, used for household decoration or special occasions. Originally referring to napkins made of cotton or linen, it evolved to include ornate embroidery, particularly favoured by young brides in their trousseau. originally denoted a rectangular piece of cotton or linen, available in various sizes, used primarily as a napkin. Often, both ends of the

yaglik

Yaglik: (Proto Turkic: yaglik – kerchief, head scarf), an embroidered textile, traditionally rectangular in shape, used for household decoration or special occasions. Originally referring to napkins made of cotton or linen, it evolved to include ornate embroidery, particularly favoured by young brides in their trousseau. were embellished with embroidery.

Over time, the term expanded in meaning to encompass embroidered textiles used for decorative purposes within the household or during special occasions.

Young brides frequently included

yaglik

Yaglik: (Proto Turkic: yaglik – kerchief, head scarf), an embroidered textile, traditionally rectangular in shape, used for household decoration or special occasions. Originally referring to napkins made of cotton or linen, it evolved to include ornate embroidery, particularly favoured by young brides in their trousseau. that was endearingly crafted by themselves and other members of their family in their trousseau as cherished possessions.

However, sashes with embroidery perhaps were not as important prior to the 18th century as embroidery in Ottoman Turkey until then, primarily emulated the luxurious woven silks and velvets found in courtly textiles.

Ottoman embroidery began to be recognised as an independent art form only after the first quarter of the 18th century when it deviated from the replication of woven designs and embraced a more creative approach. This shift allowed for the inclusion of new and naturalistic floral motifs that flowed more freely across the design field.

Simultaneously, an examination of historical artworks from Iran reveals a progressive evolution in the style of waist girdles which eventually evolved into an Ottoman

kusak

Kusak: (Turkish), a wide belt, sash or girdle worn around the waist to secure clothing. Typically made of fabric, leather, or embroidered material, it serves both practical and decorative purposes by adding a touch of elegance to traditional Ottoman attire. . During the early 16th century, it was customary for individuals in Iran to wear a leather strap adorned with metal plaques. Subsequently, this design gave way to a narrower textile band fastened with gold clasps.

Thomas Herbert, a member of an English embassy to Iran in the late 1620s, made noteworthy observations regarding the length of these sashes and the significant variations in their materials. According to him individuals of different social statuses distinguished themselves through the quality of their band and the accompanying plain, but opulent fabric towels used underneath them.

These fabrics were often made of silk and gold for nobilities, while the merchants wore them woven with silver, and lower-ranking individuals wore them in silk and wool.

Similar sashes were also prevalent in the realms, adjacent to the Safavid cultural sphere – Ottoman and Mughal. By the late 17th century, this fashion trend had not just been widely accepted in the Ottoman Empire but transcended beyond it. It had reached parts of eastern Europe, such as Poland and Russia.

Thus, the courtiers in these regions embraced the use of textiles and fashion trends imported from Ottoman Turkey as status symbols. While the style of dress amongst the aristocracy in this region as well as the Ottoman empire gradually started drawing inspiration from the West, the popularity of the sash endured as an indelible mark of Ottoman influence either as an elaborate buckled

kusak

Kusak: (Turkish), a wide belt, sash or girdle worn around the waist to secure clothing. Typically made of fabric, leather, or embroidered material, it serves both practical and decorative purposes by adding a touch of elegance to traditional Ottoman attire. or as a daintily embroidered

yaglik

Yaglik: (Proto Turkic: yaglik – kerchief, head scarf), an embroidered textile, traditionally rectangular in shape, used for household decoration or special occasions. Originally referring to napkins made of cotton or linen, it evolved to include ornate embroidery, particularly favoured by young brides in their trousseau. .

Links

- Cangökçe, Hadiye, et al. Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nun Son Döneminden Kadın Giysileri = Women’s Costume of the Late Ottoman Era from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection. Sadberk Hanım Museum, 2010.

- Küçükerman, Önder, and Joyce Matthews. The Industrial Heritage of Costume Design in Turkey. GSD Foreign Trade Co. Inc, 1996.

- AĞAÇ, Saliha, and Serap DENGİN. “The Investigation in Terms of Design Component of Ottoman Women Entari

: (Turkish; Synonym: Antari), a traditional Turkish long jacket-like unisex garment worn during the Ottoman era. It often featured an open front with long sleeves and was worn over an undershirt and a pair of trousers and was sometimes layered by a short waist or hip-length jacket. in 19th Century and Early 20th Century.” International Journal of Science Culture and Sport (IntJSCS), vol. 3, no. 1, Mar. 2015, pp. 113–125. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/91778

- Parker, Julianne. “OTTOMAN AND EUROPEAN INFLUENCE IN THE NINTEENTH-CENTURY BRIDAL COLLECTION OF THE AZEM PALACE, DAMASCUS, SYRIA.” Journal of Undergraduate Research: Brigham Young University, 18 Sept. 2013. http://jur.byu.edu/?p=6014

- Koç, Adem. “The Significance and Compatibility of the Traditional Clothing-Finery Culture of Women in Kutahya in Terms of Sustainability.” Milli Folklor , vol. 12, no. 93, Apr. 2012. 184. https://www.millifolklor.com/PdfViewer.aspx?Sayi=93&Sayfa=181

- Micklewright, Nancy. “Late-Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Wedding Costumes as Indicators of Social Change.” Muqarnas, vol. 6, 1989, pp. 161–74. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1602288. Accessed 13 July 2023.

- Micklewright, Nancy. “Looking at the Past: Nineteenth Century Images of Constantinople and Historic Documents.” Expedition, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 24–32. https://www.penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/pdfs/32-1/micklewright.pdf

- Ozgen, Ozlen, et al. “Henna Ritual Clothing in Anatolia from Past to Present: An Evaluation on Bindalli.” Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, 2021, https://doi.org/10.32873/unl.dc.tsasp.0122.

- https://artsandculture.google.com/story/traditional-jewellery-and-dress-from-the-balkans-the-british-museum/ZQXB8B6bvfnaKw?hl=en

- https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/227446

- https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/443074

- https://www.trc-leiden.nl/trc-needles/individual-textiles-and-textile-types/daily-and-general-garments-and-textiles/yagliks