Object History This

shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. was purchased in 1995 by Buthaina al Kadi,

Dr. Reem Tariq

Ṭariq: (Arabic; Synonym: tulle_bi_talli

Tūlle_bi_tallī: (French: Tulle – a city in France where fine material for veil was first made; Turkish: tel – wire; Synonym: tariq; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the North African Arab region specifically in Egypt.

; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the Levant Arab region specifically in Lebanon.

El Mutwalli

Dr. Reem Tariq

Ṭariq: (Arabic; Synonym: tulle_bi_talli

Tūlle_bi_tallī: (French: Tulle – a city in France where fine material for veil was first made; Turkish: tel – wire; Synonym: tariq; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the North African Arab region specifically in Egypt.

; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the Levant Arab region specifically in Lebanon.

el Mutwallī: Founder (CEO) of the Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative, a public figure, speaker and author. An expert curator and consultant in Islamic art and architecture, interior design, historic costume, and UAE heritage.’s mother. In time, it was added to The

Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Collection.

Object Features This square-black silk (

shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. ) of (

satin

Sātin: (Arabic: Zaytuni: from Chinese port of Zayton in Quanzhou province where it was exported from and acquired by Arab merchants), one of the three basic types of woven fabric with a glossy top surface and a dull back. Originated in China and was fundamentally woven in silk.) weave, popularly known as (

Manila_shawl

Manila_shawl: (Manila: city in Philippines, synonyms: manton_de_seda

Manton_de_seda: (Spanish, mantón: shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. , de seda – of silk, synonyms: Canton_shawl, manila_shawl, Piano_shawl

Piano_shawl: (synonyms: manton_de_seda, Manila_shawl, Canton_shawl, manton_de_Manila) A silk embroidered shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. from Canton, China –Canton_shawl – introduced to the Manila, Philippines – a Spanish colony – through Spanish trade as it passed through its port. It became synonymous to flamenco costumes and Spanish identity and were also often draped over pianos thus Piano_Shawls., manton_de_Manila), a silk embroidered shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. from Canton, China introduced to the Manila, Philippines – a Spanish colony – through Spanish trade as it passed through its port. It became synonymous to flamenco costumes and Spanish identity and were also often draped over pianos thus Piano_Shawls., manton_de_Manila

Manton_de_Manila: (Spanish, mantón: shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. , synonyms: manton_de_seda

Manton_de_seda: (Spanish, mantón: shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. , de seda – of silk, synonyms: Canton_shawl, manila_shawl, Piano_shawl

Piano_shawl: (synonyms: manton_de_seda, Manila_shawl, Canton_shawl, manton_de_Manila) A silk embroidered shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. from Canton, China –Canton_shawl – introduced to the Manila, Philippines – a Spanish colony – through Spanish trade as it passed through its port. It became synonymous to flamenco costumes and Spanish identity and were also often draped over pianos thus Piano_Shawls., manton_de_Manila), a silk embroidered shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. from Canton, China introduced to the Manila, Philippines – a Spanish colony – through Spanish trade as it passed through its port. It became synonymous to flamenco costumes and Spanish identity and were also often draped over pianos thus Piano_Shawls., Piano_shawl

Piano_shawl: (synonyms: manton_de_seda, Manila_shawl, Canton_shawl, manton_de_Manila) A silk embroidered shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. from Canton, China –Canton_shawl – introduced to the Manila, Philippines – a Spanish colony – through Spanish trade as it passed through its port. It became synonymous to flamenco costumes and Spanish identity and were also often draped over pianos thus Piano_Shawls., manila_shawl, Canton_shawl), a silk embroidered shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. from Canton, China introduced to the Manila, Philippines – a Spanish colony – through Spanish trade as it passed through its port. It became synonymous to flamenco costumes and Spanish identity and were also often draped over pianos thus Piano_Shawls., Canton_shawl, Piano_shawl

Piano_shawl: (synonyms: manton_de_seda, Manila_shawl, Canton_shawl, manton_de_Manila) A silk embroidered shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. from Canton, China –Canton_shawl – introduced to the Manila, Philippines – a Spanish colony – through Spanish trade as it passed through its port. It became synonymous to flamenco costumes and Spanish identity and were also often draped over pianos thus Piano_Shawls.) A silk embroidered shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. from Canton, China –Canton_shawl – introduced to the Manila, Philippines – a Spanish colony – through Spanish trade as it passed through its port. It became synonymous to flamenco costumes and Spanish identity and were also often draped over pianos thus Piano_Shawls.) or (

Piano_shawl

Piano_shawl: (synonyms: manton_de_seda, Manila_shawl, Canton_shawl, manton_de_Manila) A silk embroidered shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. from Canton, China –Canton_shawl – introduced to the Manila, Philippines – a Spanish colony – through Spanish trade as it passed through its port. It became synonymous to flamenco costumes and Spanish identity and were also often draped over pianos thus Piano_Shawls.), is hand embroidered with red and green silk threads of different shades.

While the vibrant combination of colours is more (

Moorish

Moorish: (noun: Moors – People of North Africa and Iberian Peninsula from Latin: mauri from ancient Greek: amouros – dark, or dim; a name designated to the Berber-speaking ethnic population of Mauritania, Northwest Africa, Iberian Peninsula, Sicily, and Malta) Christian Europeans coined it to identify the native Muslim inhabitants of this region. ) and/or Spanish in nature, the motifs and the art style are of

oriental

Oriental: (Latin and Late Middle English Adjective: orientalis – From Orient; from Latin (noun): oriri – to rise; and oriors – East), anything of an Eastern origin in relationship to Europe – Asia. The word was first used in the context of territorialization between the late 3rd and early 4th Century CE. – China and the Far East – influence making it a typical (

chinoiserie

Chinoiserie: (French: chinoiserie from French: chinois – Chinese) A European interpretation and imitation of oriental – Chinese and Far Eastern – art characterized through Chinese motifs and techniques in architecture, couture, and decorative arts from mid to late 17th Century onwards. It was easily adopted as a part of contemporary Rococo aesthetics. )

shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. . Each corner of the

shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. has a large bouquet with a peony – symbolising good fortune and honour – in the centre in shades of red and pink, bamboo leaves – symbolising longevity and strength, and butterflies – symbolising fertility and happiness. The foliage and other floral elements of the bouquet extend inwards and converge at the centre of the

shawl

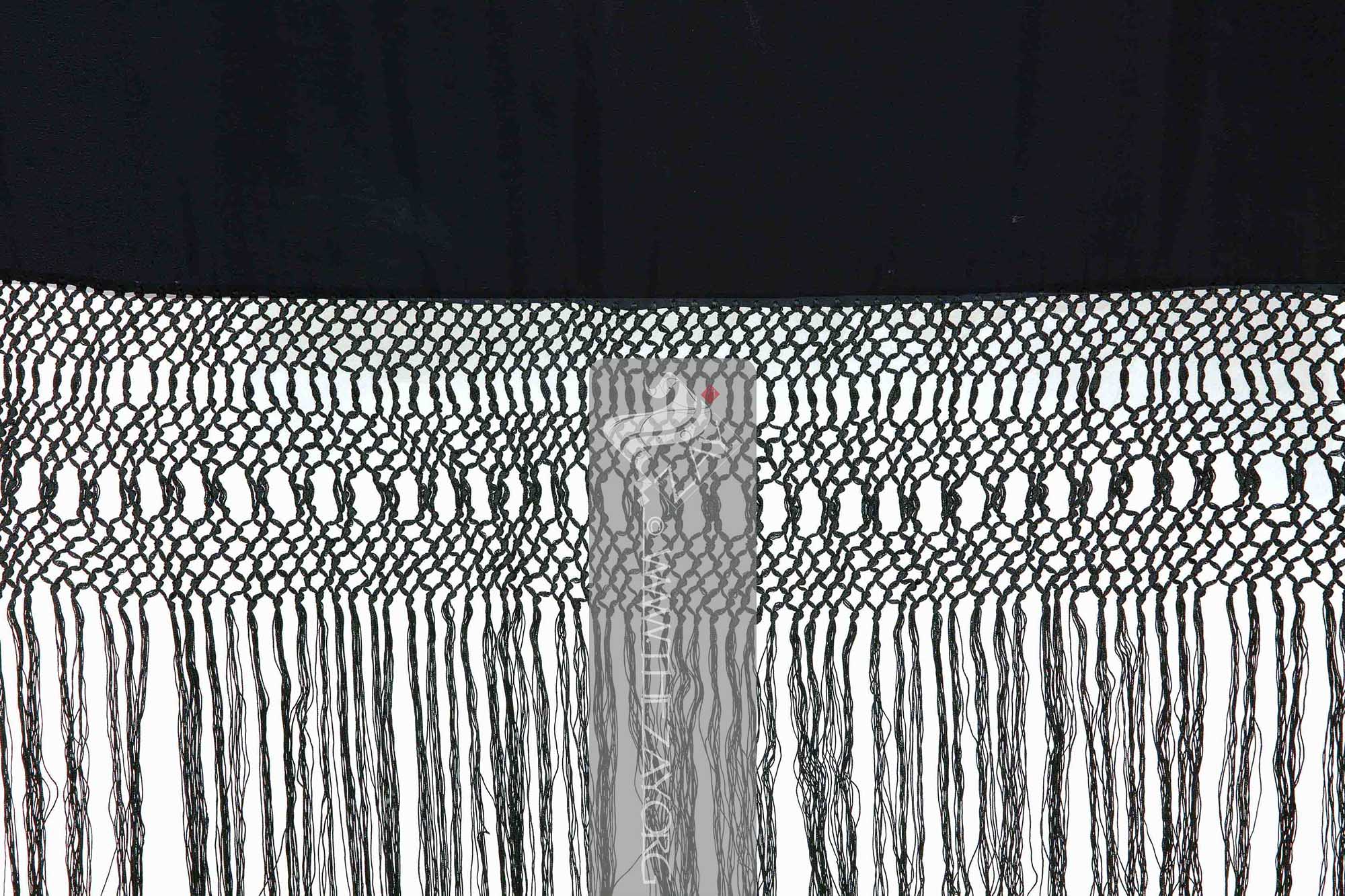

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. . Two floral bands frame the bouquets forming the border. The thin inner band consists of small flowers and leaves connected by branches, while the outer band is wider featuring small peonies, leaves, and butterflies. A 50 cm long intricate black (

macrame

Macrame: (French: macramé – A hand-knotted textile from Turkish: makrama – table spread or towel, from Arabic: miqrama – bedspread possibly with knotted hanging fringes resembling dangling grapes or karam in Arabic) A form of textile or fringe made by a knotting cord in geometrical patterns possibly originating in Babylon and Assyria.Macrame

Macrame: (French: macramé – A hand-knotted textile from Turkish: makrama – table spread or towel, from Arabic: miqrama – bedspread possibly with knotted hanging fringes resembling dangling grapes or karam in Arabic) A form of textile or fringe made by a knotting cord in geometrical patterns possibly originating in Babylon and Assyria.: makrəˌmā: (Arabic: karam: tree with dangling grapes), ornamental fringe. The art of knotting cord or string in patterns to make decorative articles. Earliest recorded uses of macramé-style knots as decoration appeared in Babylonian and Assyrian carvings.) fringe in silk adorns the edge on three sides stamping the undeniable Spanish influence.

Such shawls became an indelible part of (

flamenco

Flamenco: (Spanish: falmenco – A form of music, song & dance) An art form steeped in the traditional folklores and music from Andalusia and the Iberian Peninsula especially of the Romani culture.) costumes as they were generally draped over the shoulders like a

scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. by folding it in half diagonally. They were also used as flags on balconies during various festivals and were often placed over pianos, hence the term piano shawls.

More detailsThe Manila

shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. was first introduced in Europe by the Spanish. Originally made in Guangzhou or Canton in China, such shawls came to Europe through the port of Manila, in the Philippines travelling across the Manila Galleon Route (1565 to 1815) – from China to Philippines to Mexico to its final destination at Seville.

The earliest examples of these shawls had elements and iconographies with symbolic meanings steeped in

oriental

Oriental: (Latin and Late Middle English Adjective: orientalis – From Orient; from Latin (noun): oriri – to rise; and oriors – East), anything of an Eastern origin in relationship to Europe – Asia. The word was first used in the context of territorialization between the late 3rd and early 4th Century CE. (Far Eastern) culture and philosophies such as dragons, pagodas, flora and fauna – chrysanthemum, peony, frogs and toads, butterflies, and cranes – social scenes with men and women in (

hanfu

Hanfu:(Chinese: Hanfu – Traditional Chinese dresses) Worn by the Han Chinese people recorded since the second imperial dynasty of China – the Han Dynasty – which came to power in 2nd Century BCE these dresses greatly influenced the traditional garments of its neighbouring regions such as Japan and Korea.) and (

kimono

Kimono: (Japanese: ki : wearing, mono: thing, Singular: Kimono) A traditional Japanese long loose robe with wide sleeves tied with a sash around the waist. Presently it is the national dress of Japan. ) etc. However, a spectacular transformation started as they passed through the colonies of Mexico and the Latin Americas. The use of shawls by the colonisers and their influence on the economy led the women in the indigenous native population to learn the art of European embroidery thus catering to the growing demands of these shawls in the colonies. In the process,

oriental

Oriental: (Latin and Late Middle English Adjective: orientalis – From Orient; from Latin (noun): oriri – to rise; and oriors – East), anything of an Eastern origin in relationship to Europe – Asia. The word was first used in the context of territorialization between the late 3rd and early 4th Century CE. iconographies gave way to more occidental and indigenous native ones, the overall sizes increased and so did the size of the motifs.

In Spain however, the story was different. Legend has it that with Mexico’s independence in 1815, and the dissolution of the Manila Galleon Route this lucrative trade came to a crashing halt. However, some poor and defective quality Chinese fabrics with its original Far Eastern iconographies and designs were still in circulation in Spain possibly in the form of tobacco packaging from the Philippines. These fabrics were sometimes used as ornaments for decorative purposes by the cigarrera – cigar maker – women in Seville who popularised them in the later stage in mainland Europe. With its rising demands and Spain’s loss of the Philippines in 1898, women embroiders’ workshops were sprouting around the villages of Seville to keep up with the European demands. Far Eastern motifs and colours gave way to the cheerful Andalusian identity with sporadic incorporation of its original motifs. The attachment of the fringes – a very

Moorish

Moorish: (noun: Moors – People of North Africa and Iberian Peninsula from Latin: mauri from ancient Greek: amouros – dark, or dim; a name designated to the Berber-speaking ethnic population of Mauritania, Northwest Africa, Iberian Peninsula, Sicily, and Malta) Christian Europeans coined it to identify the native Muslim inhabitants of this region. feature – to the

shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. was the final stamp to make it uniquely Spanish in nature.

Manila shawls as we know today are modelled on these examples from the first quarter of the 19th century.

Links:

- Llodrà i Nogueras, Joan Miquel. “On Textiles, Colonies and Indians: A Tale from across the Seas”. Datatèxtil, no. 35, pp. 24-34. RACO, https://raco.cat/index.php/Datatextil/article/view/319798. Accessed 28 Jun. 2022.

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. A Short History of the Philippines. The New American Library, November 1969. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/shorthistoryofph00agon/page/n3/mode/2up. Accessed 28 Jun.2022.

- Arbues-Fandos, Natalia, Sofia Vicente-Palomino, Dolores Julia Yusá-Marco, Maria Angeles Bonet Aracil, and Pablo Monllor Perez. “The Manila Shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. Route.” Arché, no. 3, 2008, pp. 137-142. RiuNet, https://riunet.upv.es/bitstream/handle/10251/31505/2008_03_137_142.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 28 Jun. 2022.

- Izco, Jesús, and Carmen Salinero. “The Manila Shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. : Part of the Spanish Culture.” Proceedings of 2016 Dali International Camellia Congress, pp. 32-40. ResearchGate, http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4178.5200. Accessed 28 Jun. 2022.

- https://www.fashionmuseumriga.lv/eng/kaleidoscope/manila/

- https://fromspain.com/history-of-the-spanish-monton-the-manila-shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. /

- https://en-academic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/11687755