Object History This object was gifted to

Dr. Reem Tariq

Ṭariq: (Arabic; Synonym: tulle_bi_talli

Tūlle_bi_tallī: (French: Tulle – a city in France where fine material for veil was first made; Turkish: tel – wire; Synonym: tariq; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the North African Arab region specifically in Egypt.

; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the Levant Arab region specifically in Lebanon.

El Mutwalli

Dr. Reem Tariq

Ṭariq: (Arabic; Synonym: tulle_bi_talli

Tūlle_bi_tallī: (French: Tulle – a city in France where fine material for veil was first made; Turkish: tel – wire; Synonym: tariq; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the North African Arab region specifically in Egypt.

; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the Levant Arab region specifically in Lebanon.

el Mutwallī: Founder (CEO) of the Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative, a public figure, speaker and author. An expert curator and consultant in Islamic art and architecture, interior design, historic costume, and UAE heritage. by her paternal grandaunt Salimah Abdul Aziz El Mutwalli, matriarch of the El Mutwalli family.

Born in the Adhamiyah district of Baghdad in 1895, Ms Salimah never married. She resolved to run the Mutwalli family household, as custom dictated. She is a part of her elder brother, Nuri Abdul Aziz El Mutwalli’s home who in turn was the patriarch of the El Mutwalli clan and caretaker of The Sunni Shrine of Abu Hanifah Al Nu’man, (hence the name; Mutwalli: caretaker).

Although not formally educated, she could read the whole Quran as she most possibly memorised by heart. A socialite in her time, renowned for her delicious cooking, Ms. Salimah was famous for her afternoon tea receptions or salons known as “qabul” or “Istiqbal” – a monthly women's gathering where they would gather and exchange news while sipping tea, and sampling traditional Iraqi delicacies such as stuffed vines and vegetables “dolmah”, sweet pastry dumplings “klaycha” and savory bread “khubz ‘Uruq”.

She passed away in 1993 and was interred in the shrine of Imam Abu Hanifa al-Nu’man.

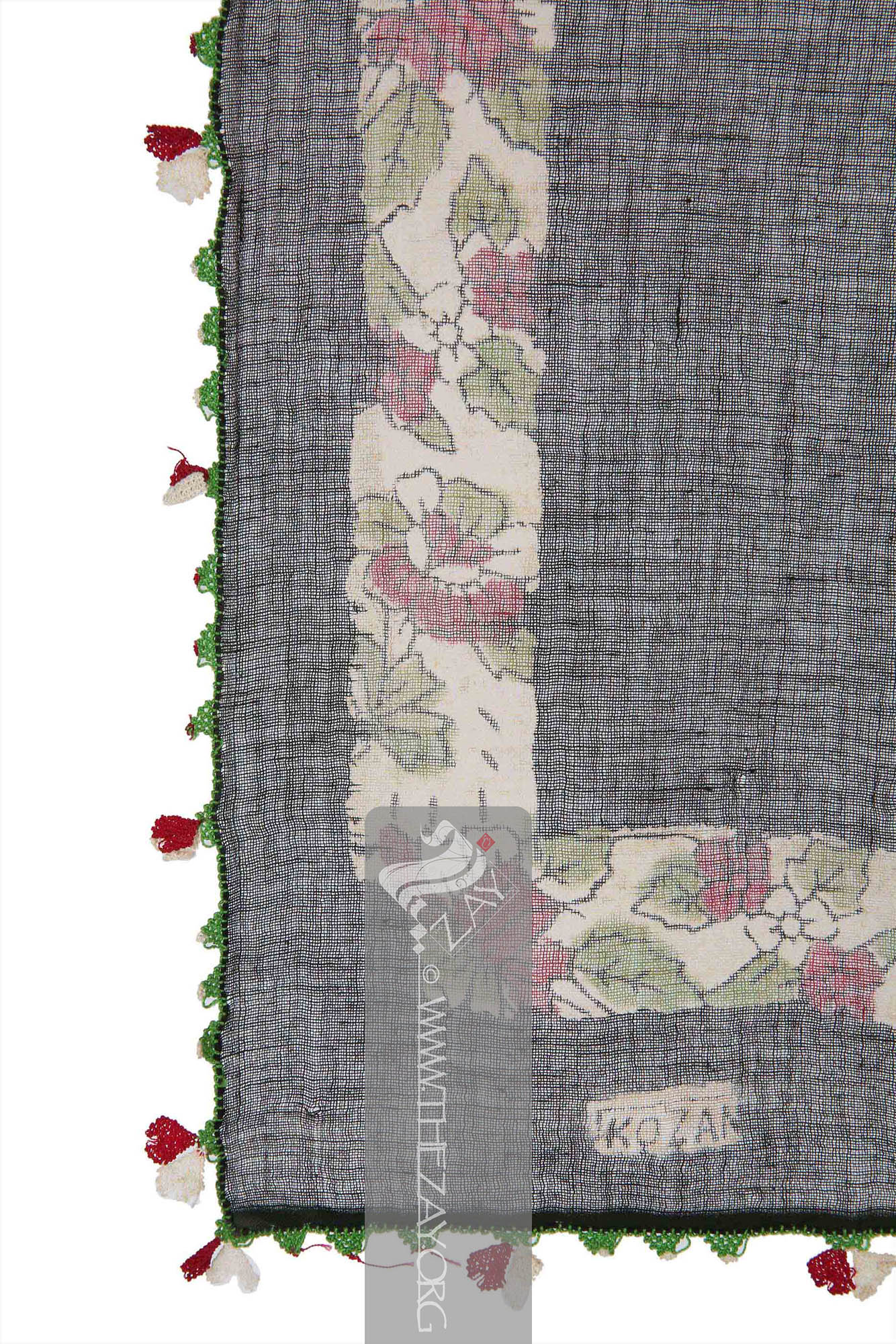

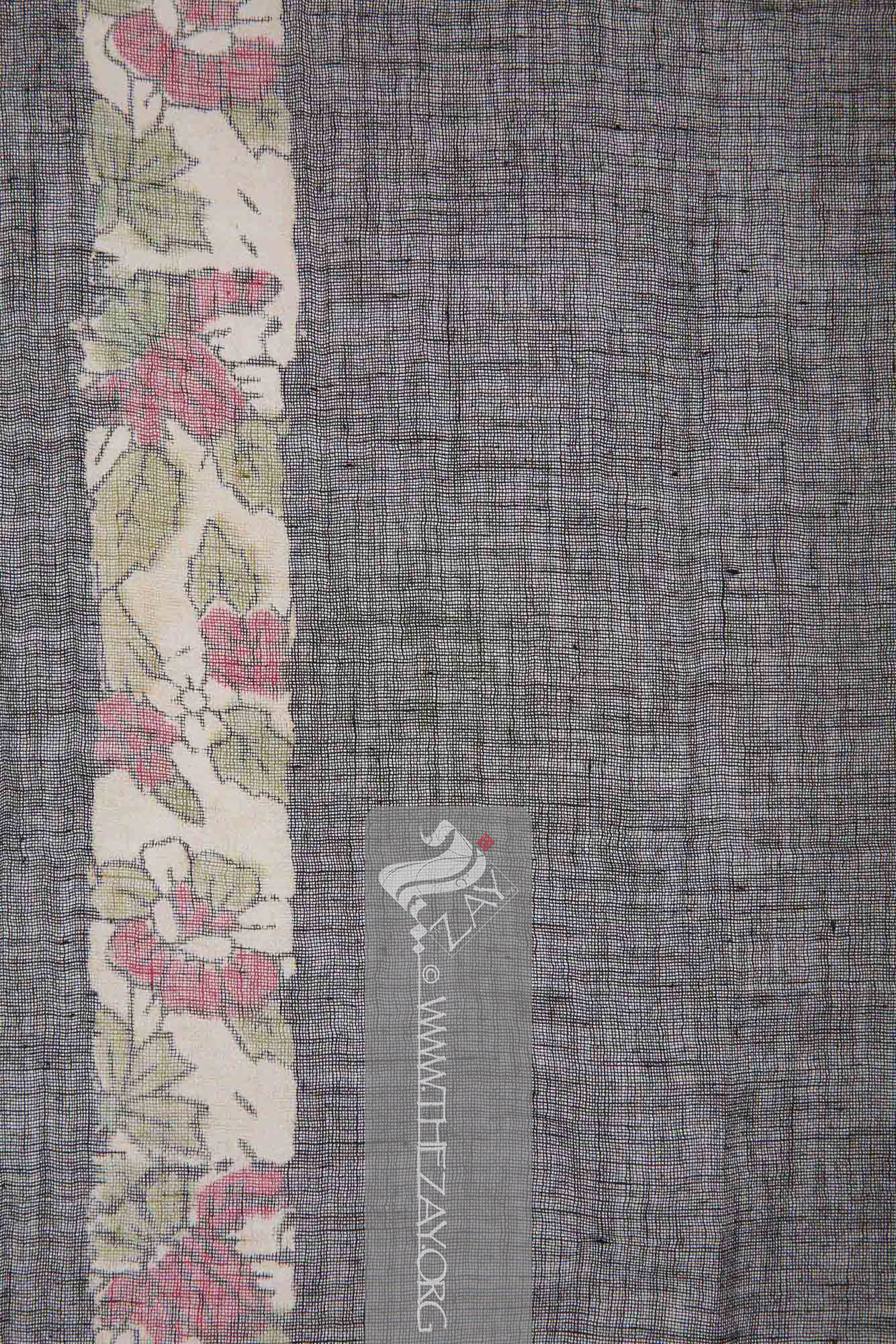

Object Features This is a square-shaped head cover or

scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. (

boyama

Boyamā: (Turkish: painting; dyeing), a square printed scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. similar to Turkish yazma

Yazma: (Turkish), a lightweight, square-shaped Turkish traditional scarf made of cotton or silk and often adorned with vibrant printed, or hand drawn colourful patterns and delicate needle lace trimmings (oya). made of cotton or silk and adorned with vibrant colourful patterns worn in the Levant and Fertile Crescent regions of the Arab world. It was a term originally assigned to dyed and patterned scarves of Turkish Ottoman origin. ) made of (block_printed) or (

resist_dyed_print

Resist_dyed_print: An old technique for printing on fabrics. The technique works by applying a dye-resistant substance, usually wax, to the fabric, and then dyeing the fabric. The dye-resistant material prevents the dye from penetrating the fabric, resulting in patterns on the fabric. Possibly known as tie-dyeing, which is a type of dye-resist printing technique, including the fabric being tied or folded in a specific way before dyeing it (tie dye), (batik), or (block print), This results in repeating geometric patterns on the fabric. ) cotton (

gauze

Gauze: (English), very fine wire mesh transparent fabric of silk, linen, or cotton.).

The field of the

scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. is primarily plain black except for a thick ivory panel spanning the perimeter of the fabric like a border with printed embellishment. The panel features a central line flanked by floral blooms possibly daffodils, and foliage in (

crimson

Crimson: (Persian/Arabic and Turkish: qirmiz or kirmiz – red), is a vivid red color originally made from the dried bodies of a scale insect of the Kermes genus native to the Mediterranean region and was used as a dye for clothing and textiles.) red and olive green with a black outline possibly printed using

block_printing

Block_printing: It is a printing technique where an image is carved into a block of wood, before being inked and stamped. Originated in China during the antiquities, with the earliest surviving examples from 220 AD it became popular and common since 7th century Tang China until the 19th century in East Asia. method.

The hem of the

scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. is picoted with a vibrant green silk thread with traditional Turkish style crocheted needle lace (

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. ) trimming featuring a double heart-shaped pattern in ivory and

crimson

Crimson: (Persian/Arabic and Turkish: qirmiz or kirmiz – red), is a vivid red color originally made from the dried bodies of a scale insect of the Kermes genus native to the Mediterranean region and was used as a dye for clothing and textiles. red. The bottom left of the

boyama

Boyamā: (Turkish: painting; dyeing), a square printed scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. similar to Turkish yazma

Yazma: (Turkish), a lightweight, square-shaped Turkish traditional scarf made of cotton or silk and often adorned with vibrant printed, or hand drawn colourful patterns and delicate needle lace trimmings (oya). made of cotton or silk and adorned with vibrant colourful patterns worn in the Levant and Fertile Crescent regions of the Arab world. It was a term originally assigned to dyed and patterned scarves of Turkish Ottoman origin. possibly features the maker’s signature or stamp.

The piece is similar to the traditional Turkish scarves (

yazma

Yazma: (Turkish), a lightweight, square-shaped Turkish traditional scarf made of cotton or silk and often adorned with vibrant printed, or hand drawn colourful patterns and delicate needle lace trimmings (oya). ) collected from Türkiye also in the collection (

ZI2021.500875.3 ASIA,

ZI2021.500875.3a ASIA,

ZI2021.500875.3b ASIA,

ZI2021.500875.3c ASIA,

ZI2021.500875.3d ASIA, and

ZI2021.500875.3e ASIA).

In certain parts of Türkiye, similar panels of fabrics can be referred to as (madil_yazma_mahrama) or (

yazma_yemeni

Yazma_yemeni: (Turkish: yazma – scarf; Arabic: yemeni – possibly from Yemen a sovereign Arab country located in the Arabian Peninsula; Synonym: mendil_yazma_makrama, mahramah), often a rectangular piece of printed or patterned fabric used as head cover and handkerchief by Ottoman women. ). However, these fabrics are more akin to kerchiefs than scarves and are typically rectangular in shape. The various names or terms for these fabrics reflect the cross-cultural exchanges between the Arab world and the Ottoman regions. The origin of the term

yazma_yemeni

Yazma_yemeni: (Turkish: yazma – scarf; Arabic: yemeni – possibly from Yemen a sovereign Arab country located in the Arabian Peninsula; Synonym: mendil_yazma_makrama, mahramah), often a rectangular piece of printed or patterned fabric used as head cover and handkerchief by Ottoman women. is uncertain, but some sources suggest that the earliest kerchiefs were possibly made of block_printed fabrics imported from Yemen. As printing facilities were later established within the empire, the term was generalized for any printed fabric.

Over time, the use of the terms

yazma_yemeni

Yazma_yemeni: (Turkish: yazma – scarf; Arabic: yemeni – possibly from Yemen a sovereign Arab country located in the Arabian Peninsula; Synonym: mendil_yazma_makrama, mahramah), often a rectangular piece of printed or patterned fabric used as head cover and handkerchief by Ottoman women. or

mandil_yazma_mahrama

Mandīl_yazma_maḥramah: (Arabic: mandil – handkerchief; Turkish: yazma – scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head.; Arabic: mahramah – handkerchief; Synonym: yazma

Yazma: (Turkish), a lightweight, square-shaped Turkish traditional scarf made of cotton or silk and often adorned with vibrant printed, or hand drawn colourful patterns and delicate needle lace trimmings (oya). _yemeni, mahramah), often a rectangular piece of printed or patterned fabric used as head cover and handkerchief by Ottoman women. declined as scarves adorned with painted or printed patterns and

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. trimmings became popular. These were simply, called

yazma

Yazma: (Turkish), a lightweight, square-shaped Turkish traditional scarf made of cotton or silk and often adorned with vibrant printed, or hand drawn colourful patterns and delicate needle lace trimmings (oya). , retained a square shape instead of being rectangular, and were primarily used as headgear.

It is worth noting that traditionally

yazma

Yazma: (Turkish), a lightweight, square-shaped Turkish traditional scarf made of cotton or silk and often adorned with vibrant printed, or hand drawn colourful patterns and delicate needle lace trimmings (oya). were either printed or painted. The term for the art of dyeing or colouring (

boyama

Boyamā: (Turkish: painting; dyeing), a square printed scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. similar to Turkish yazma

Yazma: (Turkish), a lightweight, square-shaped Turkish traditional scarf made of cotton or silk and often adorned with vibrant printed, or hand drawn colourful patterns and delicate needle lace trimmings (oya). made of cotton or silk and adorned with vibrant colourful patterns worn in the Levant and Fertile Crescent regions of the Arab world. It was a term originally assigned to dyed and patterned scarves of Turkish Ottoman origin. ) was often used to refer to scarves or

yazma

Yazma: (Turkish), a lightweight, square-shaped Turkish traditional scarf made of cotton or silk and often adorned with vibrant printed, or hand drawn colourful patterns and delicate needle lace trimmings (oya). with printed or painted patterns in the Arab regions under the Ottoman reign. As an integral part of Turkish culture, the use of these scarves transcended geographical bounds and had entered the Arab world especially the Levant and the Fertile Crescent region where it was adopted as a part of their lexicon for printed bandanas.

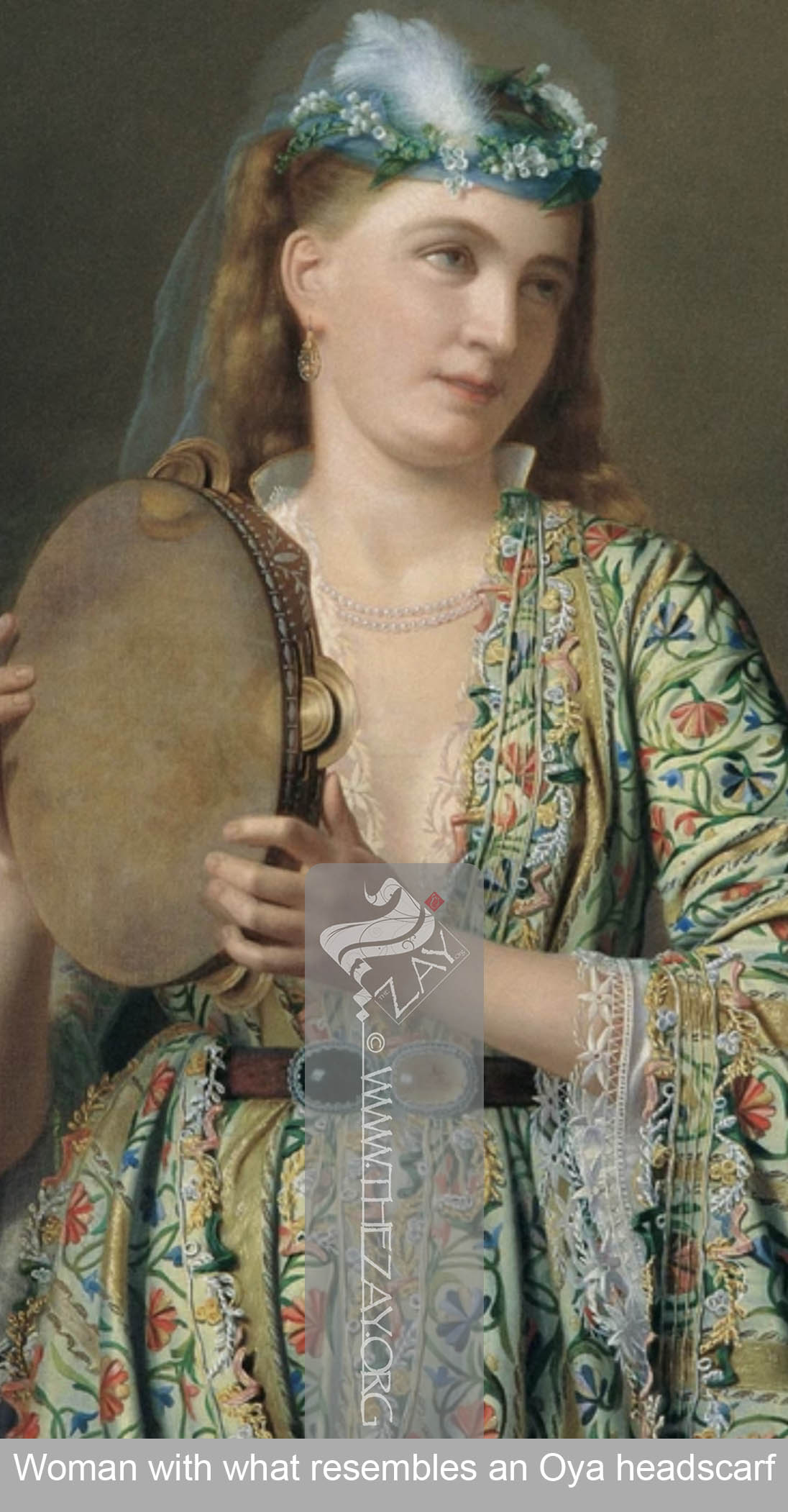

More InfoOya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. is a Turkish term used to describe narrow lace trimmings, otherwise known as "Turkish lace", in the west, are produced and worn in various regions of the Mediterranean, particularly in Türkiye. It is commonly used to adorn clothing, household textiles, and jewellery.

The art of

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. entails various forms and motifs, each bearing different names based on the techniques employed. There are four main types of

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. : needle-made

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. ,

crochet

Crochet: (French: croc - hook), a handicraft technique that involves using a hooked needle to create interlocking loops of yarn or thread to make a variety of items such as garments, accessories, and home decor. oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. , tatting

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. , and hairpin

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. . While

crochet

Crochet: (French: croc - hook), a handicraft technique that involves using a hooked needle to create interlocking loops of yarn or thread to make a variety of items such as garments, accessories, and home decor. , tatting, and hairpin lace are considered flat

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. , needle-made lace typically has a three-dimensional quality.

Traditionally

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. designs draw inspiration from nature, featuring motifs such as local, flora, and fauna. Women adorned their headdresses, scarves, and other garments with

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. , conveying emotions, expectations, and sentiments to those around them.

Different regions and age groups were associated with specific floral motifs, creating a non-verbal means of expression especially significant in various societal contexts, including engagement and wedding ceremonies, where the choice of

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. held symbolic meaning. Additionally,

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. motifs were named after prominent figures and events, reflecting societal influences.

The origin of

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. is debated. While some think that its origin dates as far back as c. 8th-century B.C.E with the Phrygians of Anatolia others believe that needle-made

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. , in particular, may have originated from Italian embroidered laces, such as Venetian needlepoint lace that travelled to Ottoman Turkey through Istanbul's close social and commercial ties with Venice from the 1500s onwards.

Whatever its beginnings may be, its long history in Türkiye since the Ottoman times leaves no doubt of its distinctive Turkish identity.

Although the origin of

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. itself is debatable, the modern flat styles of

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. have different traceable influences. It is quite likely that these styles of

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. originated in Europe between the 16th and 18th centuries and quickly spread throughout the Mediterranean regions, including Ottoman Turkey, in the latter half of the 19th century.

Historians believe this transmission may have occurred through European pattern books, handwork magazines, and publications. Local artisans then adopted and further developed these designs and techniques, resulting in a diverse range of

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. styles.

Although machine-made

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. is now available, handmade

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. remains more popular due to its perceived liveliness. Traditionally, silk and cotton yarns were used to create

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. . However, synthetic yarns have become common today.

Oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. is still a popular tradition in Türkiye. Deeply rooted in Anatolian culture, traditional

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. makers often keep an archive of loose

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. pieces, for reference.

Oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. trimmings today are not only limited to adorning women's headscarves but are also used for embellishing other modern accessories, as they continue to be cherished and preserved as part of a girl's trousseau chest.

Interestingly, as mentioned above, the use of these scarves transcended geographical bounds and entered the Arab world through Ottoman rule where the term (

mandil_oya

) or (

mandil_b_oya

: (Arabic: mandīl: scarve, Turkish: oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. : crochet technique, synonyms: oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. , mandīl_b_oyā), Embellished head scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. with hand crochet trim. ) was adopted in Egypt for example as a part of their lexicon for bandanas trimmed in

oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. technique.

Links

- Cangökçe, Hadiye, et al. Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nun Son Döneminden Kadın Giysileri = Women’s Costume of the Late Ottoman Era from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection. Sadberk Hanım Museum, 2010.

- Küçükerman, Önder, and Joyce Matthews. The Industrial Heritage of Costume Design in Turkey. GSD Foreign Trade Co. Inc, 1996.

- AĞAÇ, Saliha, and Serap DENGİN. “The Investigation in Terms of Design Component of Ottoman Women Entari

: (Turkish; Synonym: Antari), a traditional Turkish long jacket-like unisex garment worn during the Ottoman era. It often featured an open front with long sleeves and was worn over an undershirt and a pair of trousers and was sometimes layered by a short waist or hip-length jacket. in 19th Century and Early 20th Century.” International Journal of Science Culture and Sport (IntJSCS), vol. 3, no. 1, Mar. 2015, pp. 113–125. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/91778

- Parker, Julianne. “OTTOMAN AND EUROPEAN INFLUENCE IN THE NINTEENTH-CENTURY BRIDAL COLLECTION OF THE AZEM PALACE, DAMASCUS, SYRIA.” Journal of Undergraduate Research: Brigham Young University, 18 Sept. 2013. http://jur.byu.edu/?p=6014

- Hickman, Patricia Lynette. “Turkish Oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. .” University of California, Berkeley, Dec, 1977. https://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/envi/turkish_oya_v2.pdf

- Koç, Adem. “The Significance and Compatibility of the Traditional Clothing-Finery Culture of Women in Kutahya in Terms of Sustainability.” Milli Folklor , vol. 12, no. 93, Apr. 2012. 184. https://www.millifolklor.com/PdfViewer.aspx?Sayi=93&Sayfa=181

- Micklewright, Nancy. “Late-Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Wedding Costumes as Indicators of Social Change.” Muqarnas, vol. 6, 1989, pp. 161–74. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1602288. Accessed 13 July 2023.

- Micklewright, Nancy. “Looking at the Past: Nineteenth-Century Images of Constantinople and Historic Documents.” Expedition, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 24–32. https://www.penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/pdfs/32-1/micklewright.pdf

- Ozgen, Ozlen, et al. “Henna Ritual Clothing in Anatolia from Past to Present: An Evaluation on Bindalli.” Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, 2021, https://doi.org/10.32873/unl.dc.tsasp.0122.

- Denny, Walter B., and Sumru Belger Krody. The Sultan’s Garden: The Blossoming of Ottoman Art. The Textile Museum, 2012. https://museum.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaxdzs3226/f/Sultans%20Garden%20Catalogue.pdf

- Gumuser, Tulay. “Contemporary Usage of Traditional Turkish Motifs in Product Designs.” Idil Journal of Art and Language, vol. 1, no. 5, 2012, https://doi.org/10.7816/idil-01-05-14.

- https://www.trc-leiden.nl/trc/index.php/en/blog/1346-turkish-oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. -lace-at-the-trc-in-leiden

- http://www.turkishculture.org/textile-arts/oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. -70.htm