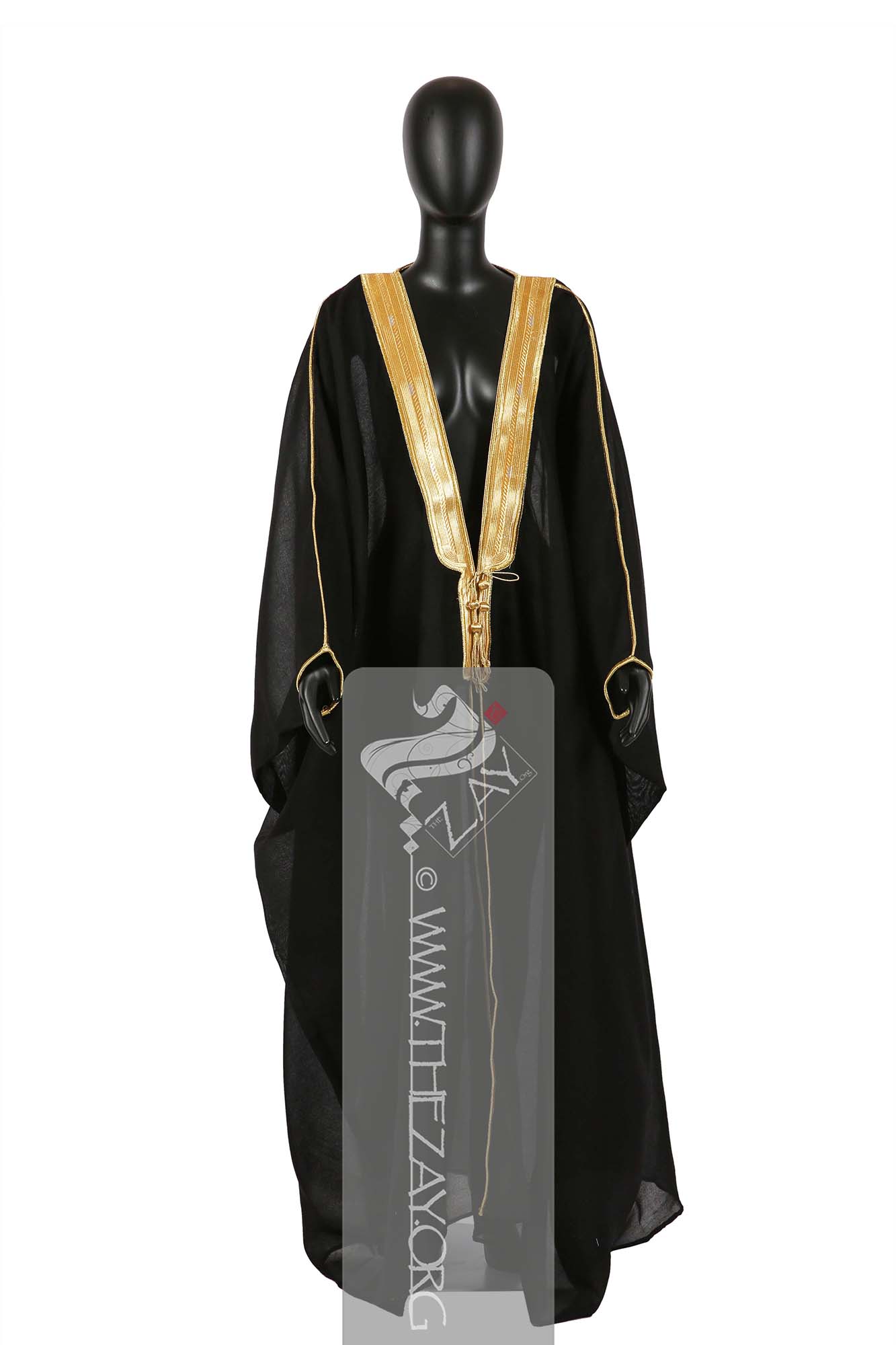

Embellished Cloak - UAE

| Local Name | Bisht, abayah |

| Object Category | Cloak |

| Gender | Male |

| Place Of orgin | Syria |

| Region | Dubai |

| Object Range | UAE, Bahrain, Iraq, Qatar, KSA, Kuwait, Oman |

| Dimensions | Length: 145 cm Width: 162 cm |

| Materials | Wool |

| Technique | Hand Stitched Embellished Woven |

| Color | |

| Motif | Geometric |

| Provenance | Donated, Noura Ahmed Khalid, UAE 2021 |

| Location | Zeman Awwal, Mall of the Emirates |

| Status | On Display |

| ZI number | ZI2018.500511 UAE |

[yotuwp type="videos" id="4Is6xPBJ110" ]

Object History

The article was donated in support of The Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative’s work by Noura Ahmed Khalid, from Dubai. It belonged to her late father Ahmed Khalid Buti, who was a merchant and passed away in 2015 at the age of 82. She had held on to it in a special trunk that helped sustain its lustrous shine.

Object Features

This formal attire (bisht

Bisht: (Arabic: bjd or bjād: cloak, Akkadian: bishtu or Persian: back, pl. bshūt synonyms: ‘Abā,‘abāyah, ‘abāh, ‘abāt, dafah

Daffah : (Arabic: side, synonyms: ‘Abā, ‘abāyah, ‘abāh, ‘abāt, bisht or mishlaḥ), long, wide, and sleeveless outer cloak worn in public by both sexes. In time this article of dress evolved and changed in shape, style, and function., or mishlaḥ), long, wide, and sleeveless outer cloak worn in public by men. In time this article of dress evolved and changed in shape, style, and function.) or (abayah

‘Abāyah: (Arabic: cloak, Pl. ‘abāyāt, or ‘Ibī. In Classical Arabic: ‘abā’ah, pl: ‘abā’āt, synonyms: ‘Abā, ‘abāh, ‘abāt, dafah

Daffah : (Arabic: side, synonyms: ‘Abā, ‘abāyah, ‘abāh, ‘abāt, bisht or mishlaḥ), long, wide, and sleeveless outer cloak worn in public by both sexes. In time this article of dress evolved and changed in shape, style, and function., bisht

Bisht: (Arabic: bjd or bjād: cloak, Akkadian: bishtu or Persian: back, pl. bshūt synonyms: ‘Abā,‘abāyah, ‘abāh, ‘abāt, dafah

Daffah : (Arabic: side, synonyms: ‘Abā, ‘abāyah, ‘abāh, ‘abāt, bisht or mishlaḥ), long, wide, and sleeveless outer cloak worn in public by both sexes. In time this article of dress evolved and changed in shape, style, and function., or mishlaḥ), long, wide, and sleeveless outer cloak worn in public by men. In time this article of dress evolved and changed in shape, style, and function., or mishlaḥ), long, wide, and sleeveless outer cloak worn in public by both sexes. In time this article of dress evolved and changed in shape, style, and function.) is often made of camel hair, goat or sheep wool, and very rarely of silk or cotton. Lighter more loose weaves are reserved for summer and denser coarser versions are used in winter. Likewise, lighter white, cream and grey colours are favoured for summer, while darker blacks and browns are suited for winter.

Worn draped on the shoulders or folded and draped on the left arm at social celebrations or formal occasions. In earlier times it was only afforded by the wealthy heads of tribes or merchants, and thus it was loaned to others and bestowed as a form of social cohesion. When UAE women wore it, draped off their heads, customarily, on very special and limited occasions, it is referred to as (sway’iyah

Sway’īyah: (Arabic: sā’ah: an hour in time or a watch, synonyms: Abā, ‘abāyah, ‘abāh, ‘abāt, dafah, bisht or mishlaḥ ), diminutive term to mean short hours or intervals. In the UAE, colloquially, it is applied to men’s style cloak (bisht) when draped off the head by women, since it was traditionally worn only for certain rare occasions. However, with oil wealth, the article evolved into more elaborate silk versions.) meaning hour, indicative of how precious the object is regarded.

Traditionally, the (bisht

Bisht: (Arabic: bjd or bjād: cloak, Akkadian: bishtu or Persian: back, pl. bshūt synonyms: ‘Abā,‘abāyah, ‘abāh, ‘abāt, dafah

Daffah : (Arabic: side, synonyms: ‘Abā, ‘abāyah, ‘abāh, ‘abāt, bisht or mishlaḥ), long, wide, and sleeveless outer cloak worn in public by both sexes. In time this article of dress evolved and changed in shape, style, and function., or mishlaḥ), long, wide, and sleeveless outer cloak worn in public by men. In time this article of dress evolved and changed in shape, style, and function.) is constructed from two equal length rectangular fabrics (fajatayn

Fajatayn: (Arabic: fajah: strip between two mountains), two strips, bolts or lengths of fabric used to measure finished cloth.) sewn together horizontally (khabun

Khabun: (Arabic), refers to the seam line in the middle of a garment, generally found on cloaks (‘ibī) and overgarments (athwāb), to shorten or lengthen it.) at mid-drift. The basic all-engulfing square shape is then created by folding the two outer edges of each (fajah

fajah: (Arabic: Fujah: gap between two mountains), denotes a single length of fabric.) to the middle and sewing the top to create the shoulder line. The lengthwise folded sides (fajatayn

Fajatayn: (Arabic: fajah: strip between two mountains), two strips, bolts or lengths of fabric used to measure finished cloth.) thus leave an opening in the middle, that runs the length of the front central line of the body. However, in this example the article appears to be composed of one wide length of fabric (fajah

fajah: (Arabic: Fujah: gap between two mountains), denotes a single length of fabric.), pointing to a machine weave rather than by hand and sports a label stating made in (Syria). Two small holes are opened at the folded line, on the top corners of each shoulder line to allow the hands to pass through creating the sleeves without having to cut and add a sleeve as in most clothes.

The middle opening of the cloak is highlighted on both sides with a dense band of hand embroidered (khwar

Khwār: (colloquial, UAE) refers to machine embroidery in silk thread (brīsam), gold metallic coil (zarī), or pure silver coil (khwār_tūlah). It typically decorates the neckline opening (ḥalj) and sleeve cuffs of the tunic (kandūrah), the chest (bidḥah) on the overgarment (thawb

Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe

Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe

Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe

Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. ) or ankle-cuffs of underpants (sarwāl). It is also known as (mkhawar

Mkhawar: (colloquial, UAE) refers to machine embroidery in silk thread (brīsam), gold metallic coil (zarī), or pure silver coil (khwār_tūlah). It typically decorates the neckline opening (ḥalj) and sleeve cuffs of the tunic (kandūrah), the chest (bidḥah) on the overgarment (thawb

Thawb: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thobe

Thobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or tobe

Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. or tobe

Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can also refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women in the Arabian Gulf region. ) or ankle-cuffs of underpants (sarwāl). It is also known as (khwār), (takhwīr), (dag), or (ḍarb).), (takhwīr), (dag), or (ḍarb).) hemline, in gilded metal wire (zari

Zarī: (Persian two-syllables: zar: gold & dozi: embellishment), complex embroidery technique that uses metal alloy on silk, satin, or velvet, and may include pearls, beads, and precious stones. Colloquially in the Arab gulf region, the term (zarī) is loosely applied to any gilded thread, embellishment or gilded brocade fabric. Originated in ancient Persia it has been used extensively in Indian and Middle Eastern textiles for centuries. ) creating a 3 cm - 7cm wide lapel shape known as (darbawiyah

Darbawīyah: (Arabic: darb: path, Turkish: oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. : engraving, trimming or embroidery), a term used in the Arab Gulf region to identify the decorative adornment used on the formal cloak (bisht).), that surrounds the neckline at the back and extends to waist level in front (on female versions the size of this opening varies to allow the article to rest on the crown of the head). The gilded metal wires (zari

Zarī: (Persian two-syllables: zar: gold & dozi: embellishment), complex embroidery technique that uses metal alloy on silk, satin, or velvet, and may include pearls, beads, and precious stones. Colloquially in the Arab gulf region, the term (zarī) is loosely applied to any gilded thread, embellishment or gilded brocade fabric. Originated in ancient Persia it has been used extensively in Indian and Middle Eastern textiles for centuries. ) were earlier imported from India, though at present the German, French or Japanese variety are held in higher regard. The darbawiyah

Darbawīyah: (Arabic: darb: path, Turkish: oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. : engraving, trimming or embroidery), a term used in the Arab Gulf region to identify the decorative adornment used on the formal cloak (bisht). is composed of a number of vertical embroidery lines, where the gilded wire on each is applied over a base created by a half a centimetre thick bundle of cotton threads, to form a raised three-dimensional surface. Each line has a specific name and geometric design, starting at the outer edge with (mkasar), (tarchib), (smut), (haylah

haylah (Arabic : cardamon seed), refers to the raised three-dimensional main embroidery pattern applied in general on the abayah, that loosely resembles a line of cardamon seeds. It can come in many stylised versions identified by particular names such as; malakī, mrūba‘, mkhūmas, mtūsa‘, ṭabūq, bakhīah zarī.), (bruj

Brūj: (Arabic: towers, sing: burj), In the UAE the term refers to the repetitive stepped tower shapes created by embroidery or (tallī) adornment.), (tanbit), and ending with (tal‘is)- see detailed image. Commercial, more affordable versions are created today through precise laser guided automated machinery in factories in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere.

The darbawiyah

Darbawīyah: (Arabic: darb: path, Turkish: oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. : engraving, trimming or embroidery), a term used in the Arab Gulf region to identify the decorative adornment used on the formal cloak (bisht). ends with one gilded cord (gitan

Gītān: (Arabic: qītān: cord or shoe-lace), comes in woven/braided colored silk or metallic thread, used in hemming or embroidery. The letter (qāf) is colloquially pronounced (ga).) that extends the remaining length of the article. The same cord (gitan

Gītān: (Arabic: qītān: cord or shoe-lace), comes in woven/braided colored silk or metallic thread, used in hemming or embroidery. The letter (qāf) is colloquially pronounced (ga).) is used extended horizontally to mark the shoulder line and hem the two hand openings. At the point where the darbawiyah

Darbawīyah: (Arabic: darb: path, Turkish: oya

Oyā: (Turkish), refers to various forms of narrow needle lace trimmings common to eastern and southern Mediterranean regions and parts of Armenia. Believed to be a derivative of Venetian lace it is considered an indelible part of the traditional craft of Türkiye today. : engraving, trimming or embroidery), a term used in the Arab Gulf region to identify the decorative adornment used on the formal cloak (bisht). ends and gitan

Gītān: (Arabic: qītān: cord or shoe-lace), comes in woven/braided colored silk or metallic thread, used in hemming or embroidery. The letter (qāf) is colloquially pronounced (ga). begins or there about, two additional 25 cm long loose cords are attached that end with a number of ball-shaped knots (‘amayil) to help fasten the article at waistline.

Historically, the finest was woven in Najaf (Iraq) and Al Ahsa’ (KSA). Presently, the finest quality is imported from Japan, Switzerland, and London, with Japan regarded as exporting the best in quality. However, the Najfi (from Najaf) and Hasawi (from Al Ahsa’) are still held in high regard. They come in many different names.