Object HistoryThis

shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. was purchased by

Dr. Reem Tariq

Ṭariq: (Arabic; Synonym: tulle_bi_talli; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the Levant Arab region specifically in Lebanon.

El Mutwalli

Dr. Reem Tariq

Ṭariq: (Arabic; Synonym: tulle_bi_talli; talli; badla; khus_dozi ), series of small metal knots made on a woven net ground as embellishment. The term is commonly used in the Levant Arab region specifically in Lebanon.

el Mutwallī: Founder (CEO) of the Zay

Zay: (Arabic: costume, Pl. azyaā’), a set of clothes in a style typical of a particular country or historical period. Initiative, a public figure, speaker and author. An expert curator and consultant in Islamic art and architecture, interior design, historic costume, and UAE heritage. on one of her trips to Canada. It is an excellent example of how traditional techniques and practices are continued to be adopted in the textile industry.

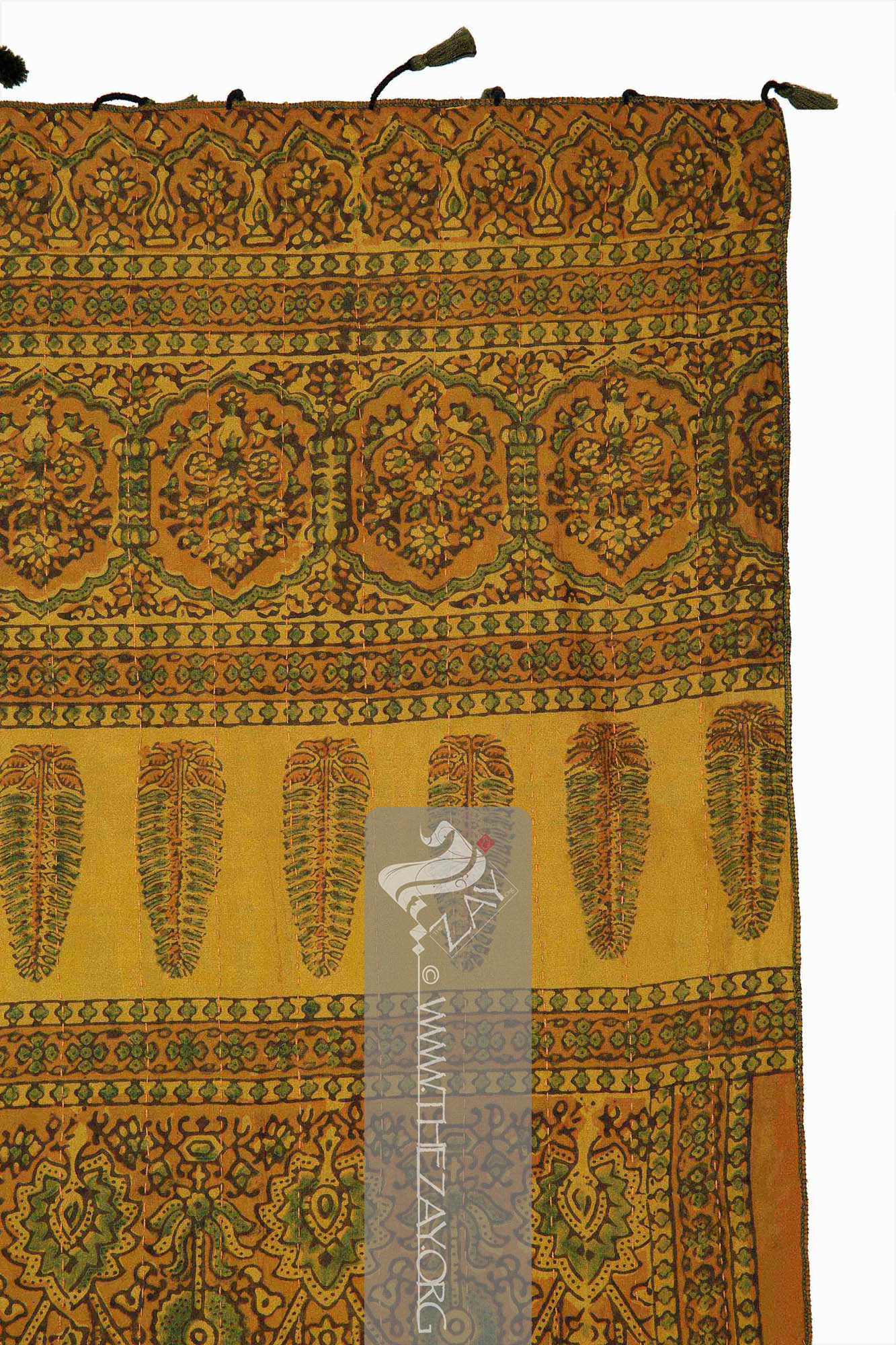

Object Features This (

ochre

Ochre: (Greek: ōkhra – Yellow Ochre), is a natural earth pigment that ranges in colour from yellow to red-brown, often used in art and decoration. ) yellow (

chanderi

Chanderi: (Hindi: Chander – a town in India), is a luxurious fabric woven with silk, cotton, and zari yarn. With a history dating back to the mid to late antiquities in the subcontinent, it reached its peak in popularity, quality, and technique under the patronage of the Mughals. ) silk (

shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. ) resembling the 19th century European (

long_shawl

Long_Shawl: (Synonym: Kirking Shawl), European versions of and inspired by Kashmiri double shawls in wool or silk manufactured locally in Europe. As a part of the trousseau for aristocratic women, it was often used at their first post-wedding church services and christenings. ) in dimension is a 21st-century printed piece. Embellished with (

ajrakh

Ajrakh: (Persian: ajar/ajor – brick; ak – small), a traditional form of block printing using resist dyeing techniques and natural dyes. Believed to have originated during the Indus Valley period of the subcontinent the modern practice has a history of at least 400 years within the Khatri community of Sindh and Gujarat. ) printed floral motifs in green and brown it has a cotton canvas lining machine stitched to its underside and rows of a single line (

kantha

Kantha: (Bengali: kantha. – quilt), is a type of embroidery involving simple running stitches to create intricate designs on fabric. Originated in the rural areas of the Bengal region of the Indian subcontinent, it was traditionally used to create practical items of regular use before evolving into a form of decorative art.) or quilt-style embroidery running all across it. Both the canvas fabric and the thread used for the

kantha

Kantha: (Bengali: kantha. – quilt), is a type of embroidery involving simple running stitches to create intricate designs on fabric. Originated in the rural areas of the Bengal region of the Indian subcontinent, it was traditionally used to create practical items of regular use before evolving into a form of decorative art. embroidery are of the same shade or

ochre

Ochre: (Greek: ōkhra – Yellow Ochre), is a natural earth pigment that ranges in colour from yellow to red-brown, often used in art and decoration. as the base fabric.

The intricate yet dense design decorating the entire

shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. is executed using a very specific (

block_printing

Block_printing: It is a printing technique where an image is carved into a block of wood, before being inked and stamped. Originated in China during the antiquities, with the earliest surviving examples from 220 AD it became popular and common since 7th century Tang China until the 19th century in East Asia.) technique –

ajrakh

Ajrakh: (Persian: ajar/ajor – brick; ak – small), a traditional form of block printing using resist dyeing techniques and natural dyes. Believed to have originated during the Indus Valley period of the subcontinent the modern practice has a history of at least 400 years within the Khatri community of Sindh and Gujarat. – that originated and is unique to the Sindh and Gujarat regions of the Indian subcontinent. The piece can be broadly divided into two (

phala

Phāla: (Etymological origin: Possibly Indo Persian), the wider layer of pattern that forms the border at each warp end or head of a shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. . ), a pair of (hashiya), and a (

matan

Matan: (Arabic, middle of the thing), the main field of a shawl. ); however, it does not follow the traditional style. Instead, its modernity is reflected through the non-traditional distribution of the design elements specially in the

phala

Phāla: (Etymological origin: Possibly Indo Persian), the wider layer of pattern that forms the border at each warp end or head of a shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. . and the hashiya.

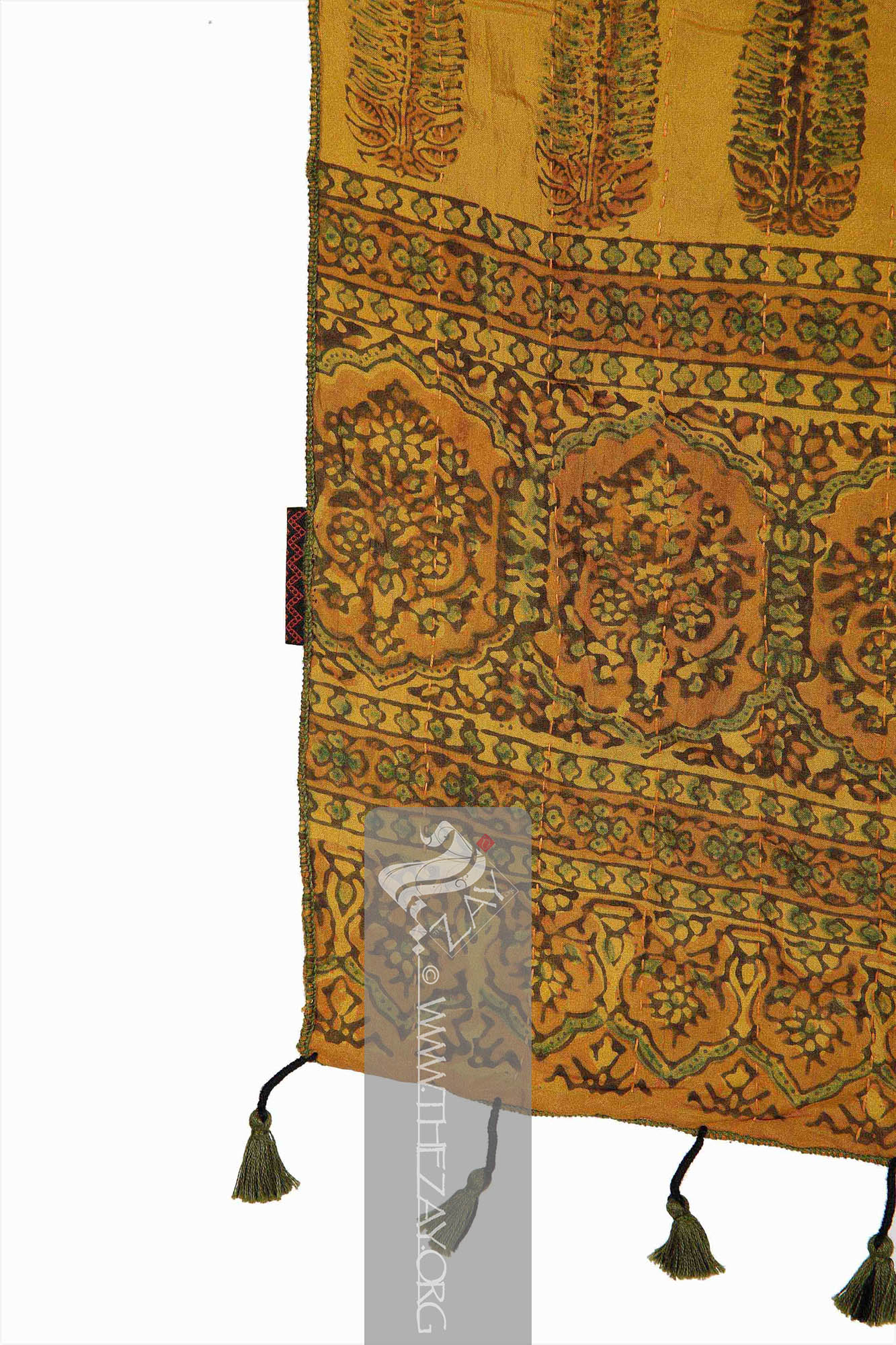

Traditionally a hashiya would run along the entire length of the

shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. sometimes even merging with the (

tanjir

Tanjīr: (Possibly Persian: zanjir: Chain), a narrow layer of pattern that forms the border and runs above and below the wider layer. ) in the corners if both had similar designs. In this

shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. the hashiya runs only the length of the

matan

Matan: (Arabic, middle of the thing), the main field of a shawl. thus creating a frame around it. It is composed of a repeat of a four-leaf clover-like floral motif in a line and is encased between two thinner lines with a similar motif but on a smaller scale.

The

phala

Phāla: (Etymological origin: Possibly Indo Persian), the wider layer of pattern that forms the border at each warp end or head of a shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. . is composed of a total of six layers. The outermost layer is repeated with a floral arrangement of a (

palmette

Palmette: (French: Palmette – Small palm, synonym Greco-Roman: Anthemion), a decorative element, motif, or ornament particularly pertaining to designs of architecture and decorative arts that has radiating petals resembling a palm leaf. It is believed to have originated in ancient Egypt and had subsequently reached far and wide. ) like bloom between stylized columns. The second, fourth, and sixth layers resemble the hashiya. The third layer consists of stylized archways separated by stylized columns. Each archway is in the form of a hexagon and displays an elaborate floral bouquet within it. A floral (

jaal

Jaal: (Sanskrit: jaal – A net, web, or a mesh), the decoration which fills the ground between the paisley cones at the heads of a shawl.

) fills the spaces between the archways. The fifth layer has seventeen tree motifs arranged in a single line. Resembling a cypress or pine tree these motifs are composed of green foliage and brown branches and roots.

The

matan

Matan: (Arabic, middle of the thing), the main field of a shawl. or body of the

shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. is densely packed with alternate repeats of a fully blossomed flower with foliage at its base and top and a

palmette

Palmette: (French: Palmette – Small palm, synonym Greco-Roman: Anthemion), a decorative element, motif, or ornament particularly pertaining to designs of architecture and decorative arts that has radiating petals resembling a palm leaf. It is believed to have originated in ancient Egypt and had subsequently reached far and wide. . The space between the motifs is filled with intricate and complex floral arrangements. The

shawl

Shawl: (Persian: shāl from Hindi: duśālā – Shoulder Mantle), a shawl is a South Asian version of a scarf

Scarf: (English), usually a rectangular piece of cloth loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. worn or wrapped loosely over the shoulders and is usually made of wool. is finished with a series of fringes created by twisted black threads and small green pompoms attached to the (

warp

Warp: One of the two basic components used in weaving which transforms thread or yarns to a piece of fabric. The warp is the set of yarns stretched longitudinally in place on a loom before the weft

Weft: one of the two basic components used in weaving that transforms thread or yarns into a piece of fabric. It is the crosswise thread on a loom that is passed over and under the warp threads. is introduced during the weaving process. ) ends.

More InfoAjrakh

Ajrakh: (Persian: ajar/ajor – brick; ak – small), a traditional form of block printing using resist dyeing techniques and natural dyes. Believed to have originated during the Indus Valley period of the subcontinent the modern practice has a history of at least 400 years within the Khatri community of Sindh and Gujarat. is a traditional form of block printing that has been practiced for centuries in the Gujarat and Sind provinces of India and Pakistan respectively. Passed down from generation it involves a meticulous printing process of natural dyes and resists into intricate designs.

The origins of

ajrakh

Ajrakh: (Persian: ajar/ajor – brick; ak – small), a traditional form of block printing using resist dyeing techniques and natural dyes. Believed to have originated during the Indus Valley period of the subcontinent the modern practice has a history of at least 400 years within the Khatri community of Sindh and Gujarat. printing can be traced back to the Indus Valley Civilization (c. 8000 BCE – 1300 BCE). Early human settlements in the lower valley of the Indus River and its tributaries had gathered the knowledge of cultivating and using cotton fiber to make clothes similar to ancient Egypt. Several archaeological remains – e.g. the bust of the Priest King at the National Museum of Pakistan – excavated from the ruins of the Indus Valley region proves the existence of resist dyeing and block printing techniques.

Although the tools and equipment used for the procedure is universal to block printers across the subcontinent, the technique is unique, laborious and time-consuming. Beginning with the washing of the fabric – traditionally cotton or silk – to remove any impurities, to soaking in a solution of a natural dye and mordant that would help fix the colours – the traditionally

indigo

Indigo: (Latin: Indigo – India, synonym: nil

Nīl: (Latin: indigo), Arabised term for Indigo, a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that have been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye.), a natural dye belonging to the ‘Indigofera Tinctoria’ species of plants that has been cultivated in East Asia, Egypt, India, and Peru since antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, it was named after India as it was the source of the dye. , root of

madder

Mādir: (Latin: Rubia tinctorum – Eurasian herb), rose madder, common madder or dyer's madder is a vegetable dye made from the roots of a perennial plant belonging to the bedstraw and coffee family. It has been used extensively as a vegetable red dye across the globe from India to England. , pomegranate rind etc – to the fabric all have a uniqueness in its execution and methods that requires great skill and patience.

Intricately hand-carved wooden blocks are used for dabbing the colour before transferring the ink by stamping it on the fabric – a procedure that is repeated for every stamp. Once the fabric is stamped and printed it is line-dried in a large open space before washing it to remove any excess dye and then treated with alum and tamarind paste to set the colours.

Traditionally a true

ajrakh

Ajrakh: (Persian: ajar/ajor – brick; ak – small), a traditional form of block printing using resist dyeing techniques and natural dyes. Believed to have originated during the Indus Valley period of the subcontinent the modern practice has a history of at least 400 years within the Khatri community of Sindh and Gujarat. fabric was only worn by men and a true

ajrakh

Ajrakh: (Persian: ajar/ajor – brick; ak – small), a traditional form of block printing using resist dyeing techniques and natural dyes. Believed to have originated during the Indus Valley period of the subcontinent the modern practice has a history of at least 400 years within the Khatri community of Sindh and Gujarat. block must be a square with four matching sides and corners.

Practiced since ancient times, the tradition grew from the combination of local skills and needs thus generating and developing isolated sub-styles within the craft. However, it was not until the Mughal patronage that a deep influence of strong geometry was seen that is often associated with the craft today. During this time the blocks were designed following the Islamic architectural element of balance and order – Mizan – where repetition of patterns was determined by grids and symmetric representation of the elements were portrayed.

The involvement of the Muslim Khatri community of the region in the craft for over four centuries made them the torch bearers as they developed and passed their skills and knowledge to the younger generations. Each family within the community has their own secret process and techniques or uniqueness in its recipe for colours. No two families will follow the same sequence of procedures or even names of materials and print pastes thus making each piece of

ajrakh

Ajrakh: (Persian: ajar/ajor – brick; ak – small), a traditional form of block printing using resist dyeing techniques and natural dyes. Believed to have originated during the Indus Valley period of the subcontinent the modern practice has a history of at least 400 years within the Khatri community of Sindh and Gujarat. cloth unique.

Today with worldwide recognition

ajrakh

Ajrakh: (Persian: ajar/ajor – brick; ak – small), a traditional form of block printing using resist dyeing techniques and natural dyes. Believed to have originated during the Indus Valley period of the subcontinent the modern practice has a history of at least 400 years within the Khatri community of Sindh and Gujarat. print is not just celebrated for its intricate designs and vibrant colours but also its sustainability. From textiles to decorative items, it has become synonymous with the cultural heritage of both Sind and the Kutch region of Gujarat.

Links