Introduction

Following our discussion on the origin of the kaftan in the previous segment, which spans from Central Asia to the Caucasus, we will now examine its spread within the global fashion landscape under Ottoman patronage. This segment of the article will retrace the kaftan’s journey into the Arab world, with a particular focus on Arab North Africa.

The Ottoman Influence

The Ottoman Empire (c. 1299 – 1922) played a crucial role in populariszing the kaftan, particularly in Middle and Near Eeast and around the Mediterranean. During c. 16th century, the kaftan became an essential garment for sultans and high-ranking officials, often layered for both stylistic and practical reasons. These ornate kaftans, made from rich materials and elaborate embellishments, were frequently gifted to important visitors and political figures. An example of this is the kaftan belonging to Suleiman the Magnificent, which was recently restored, underscoring its continued cultural significance.

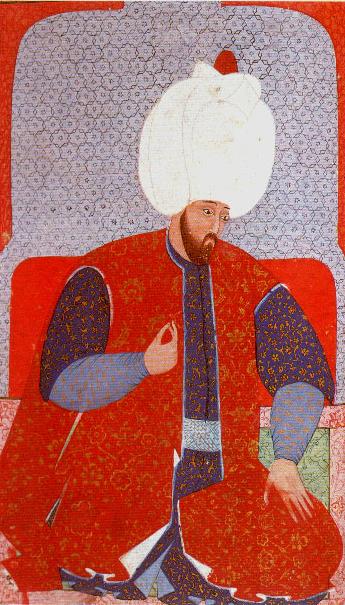

Portrait of the Ottoman Sultan Suleyman;

‘Suleyman the Magnificent as a young man’ by Nakkaş Osman from Semailname, Istanbul, c. 1563;

Acc. No: Hazine. 1563, folio 47b, Topkapı Palace Museum

The Ottoman Empire, drawing from Seljuk influences in Anatolia and integrating Western elements from Italy, developed a highly sophisticated and luxurious textile tradition characteriszed by bold and delicate designs. Kaftans were traditionally worn by the Ottoman sultans, serving as symbols of rank and status. The decoration of the garment, including its colours, patterns, ribbons, and buttons, was indicative of the wearer’s position within the hierarchy. In the first half of the 14th century, Orhan Ghazi captured Bursa and established it as the Ottoman capital. Bursa was renowned for its gold embroidery and other weaving specialities.

Following the Ottoman conquest of Istanbul in 1453, the Turkish ‘lonca’ (Islamic guild) system, infused with religious characteristics, supplanted the Byzantine guild system. Post– 15th century, textiles assumed a significant role in the social and economic fabric of the Ottoman classical period. The textile industry came under the purview of the Ehl-i Hiref organiszation, which operated under the centraliszation efforts of the Ottoman government.

During the reign of Sultan Mehmed II (1444-1446, 1451-1481), silk velvets ‘kedife’ (pile floss fabric) (from Arabic: قَطِيفَة qaṭīfa, meaning plush velvet) were produced by Kadife-i bâfâns, who were part of or under the control of the Ehl-i Hhiref in Bursa. The Ottoman conquest of Caffa in 1475 disrupted Genoese control over trade in the Black Sea and Caffa, establishing Bursa as the centre of silk trading.

Historical records from the Bursa Kadı Sicil reveal that velvets with metallic threads were woven by slaves seeking manumission (mükâtebe) in c. late 15th century. Another archival document from 1494 notes the preparation of two kaftans made of the finest Bursa gold-brocaded velvet, lined with kemha from Yezd in Iran, for the circumcision of Gelibolu Bey Sinan Pasha’s two sons. Accounts from c. late 15th to the early 16th century indicate that the ‘hil’ats’ kaftans given to Idrisi Bitlisi by Sultan Bayezid II were predominantly made of Ottoman velvets rather than ‘Frengi’ (European) textiles.

From the 14th to the 17th century, textiles featuring large patterns were prevalent. By the late 16th and early 17th centuries, the decorative patterns on fabrics had become smaller and more vibrant. While most textiles were manufactured in Istanbul and Bursa, some were imported from distant regions such as Venice, Genoa, Persia (Iran), India, and China.

It is noteworthy that velvets adorned with dot motifs were highly popular among the early Ottomans. This pattern, while also prevalent in the Middle East and Europe, was particularly favoured by the Ottomans, who often employed a distinctive three-dot motif with various patterns from the fifteenth century onwards. Archival records indicate that numerous kaftans made from Ottoman textiles featuring dot motifs were bestowed upon ‘nakkaş’, or imperial artisans, during the reign of Bayezid II (1481-1512). Specifically, historical documents reveal that such a kaftan was presented to Nakkaş Hasan between 1504 and 1512. Fabrics, including velvets with dot motifs, were in high demand among the Ottomans and represented an international fashion trend from the 14th to 16th centuries throughout the Mediterranean region.

Adoption in the early Islamic Arab world

During the Abbasid Caliphate (750-1258 CE), which coincided with the Tang era (618 – 907 CE) in China, the kaftan gained significant prominence on the global fashion landscape. Not only was the kaftan embraced by the aristocracy of Tang China, but it also became notable in Byzantine culture. By c. the 830s, Byzantine Emperor Theophilus, who engaged in conflicts with the Abbasids and constructed a Baghdad-style palace near the Bosporus, was known to don kaftans and turbans.

It is noteworthy that although the Abbasids were Arabs, their origins in Baghdad and their close ties to Central Asia and Persia significantly influenced their cultural practices. Given that the kaftan originated in Persia and Turkic Central Asia, it is unsurprising that the Abbasids were among the first Arabs to adopt and propagate this garment. The Abbasid royalty and aristocracy were known to favour luxurious kaftans crafted from silver or gold brocade, adorned with buttons on the sleeves.

Adoption and Regional Adaptations in Ottoman Arabia

The kaftan spread to the Arab East significantly with the Ottoman conquest of these regions in the 16th century. In this context, it became part of a wardrobe that included various similar garments such as the zubūn, sayah, qumbāz, and dglah. However, in North Africa the story was a little complicated.

Striped Silk Jacket (A Syrian Qumbāz), Damascus, c. 1900s; Acc.No: ZI2021.500908.3 SYRIA; Source: The Zay Initiative Collections, Link

Silk Damask Robe (An Iraqi sāyah), Iraq, c. 20th century; Acc.No: ZI2019.500701.2 IRAQ; Source: The Zay Initiative Collections, Link

The Encyclopaedia of Islam says that it was introduced into the Barbary States by the Ottomans and spread by fashion as far as Morocco. While some historians like Rachida Alaoui traces the Moroccan kaftan back to the late 15th century, linking it to the region’s Moorish heritage and medieval history of Al-Andalus, others like Naima El Khatib Boujiba suggests that the kaftan might have been introduced to Morocco by the Saadi Sultan Abd al-Malik. This theory may seem more plausible in the light of the fact that the earliest written record of the garment in Morocco dates to the 16th century. However, the earlier theory cannot be entirely dismissed. It is plausible that the kaftan was introduced to Morocco around the 15th century during the Marinid Sultanate (1244-1465 CE) as a consequence of the Spanish Inquisition. It is believed that during the Abbasid era, the kaftan reached Andalusia and subsequently made its way to Morocco with the expelled Jews and Muslims during the Inquisition.

Either way, it was not until the reign of Abd al-Malik that the kaftan was integrated within the Moroccan society. Abd al-Malik, who had lived in Algiers and Istanbul, owed his throne to Ottoman support, with Ottoman troops aiding his conquest of Fez c. 1576 CE. While he achieved functional independence from the Ottomans, he continued to acknowledge Ottoman overlordship, adopting Ottoman fashion, military, and administrative practices.

Abd al-Malik’s successor, Ahmad al-Mansur, however, did not view himself as an Ottoman subordinate but rather as an equal and rightful leader of the Islamic world, aligning with the Spanish. His assertion of independence almost cost him his throne. Facing powerful enemies such as the rising Safavids of Persia, the seat of Shī’ite Islam, and following the Ottoman’s’ peace treaty with Spain, al-Mansur could not afford another conflict with the Ottomans. Thus, at least until around 1587, Ottoman influence persisted in Morocco.

The kaftan became deeply associated with Moroccan culture, especially during the reign of Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur when it was worn as a two-piece garment. This version, known as Al-Mansouria, spread to the working class during the Saadi Dynasty (1554–1636 AD), evolving into an everyday garment made from finer silks and cotton, while more elaborate versions were reserved for special occasions.

National Symbolism and Contemporary Significance

The kaftan or (qaftan) remains a significant national symbol in Morocco and Algeria, often associated with power and tradition. In Morocco, it is a key article of traditional dress for both men and women, with judges historically wearing the kaftan (qaftan) as a symbol of authority. The garment’s role as a national symbol can also lead to tensions, as seen in the cultural disputes between Morocco and Algeria over the origins of the kaftan (qaftan).

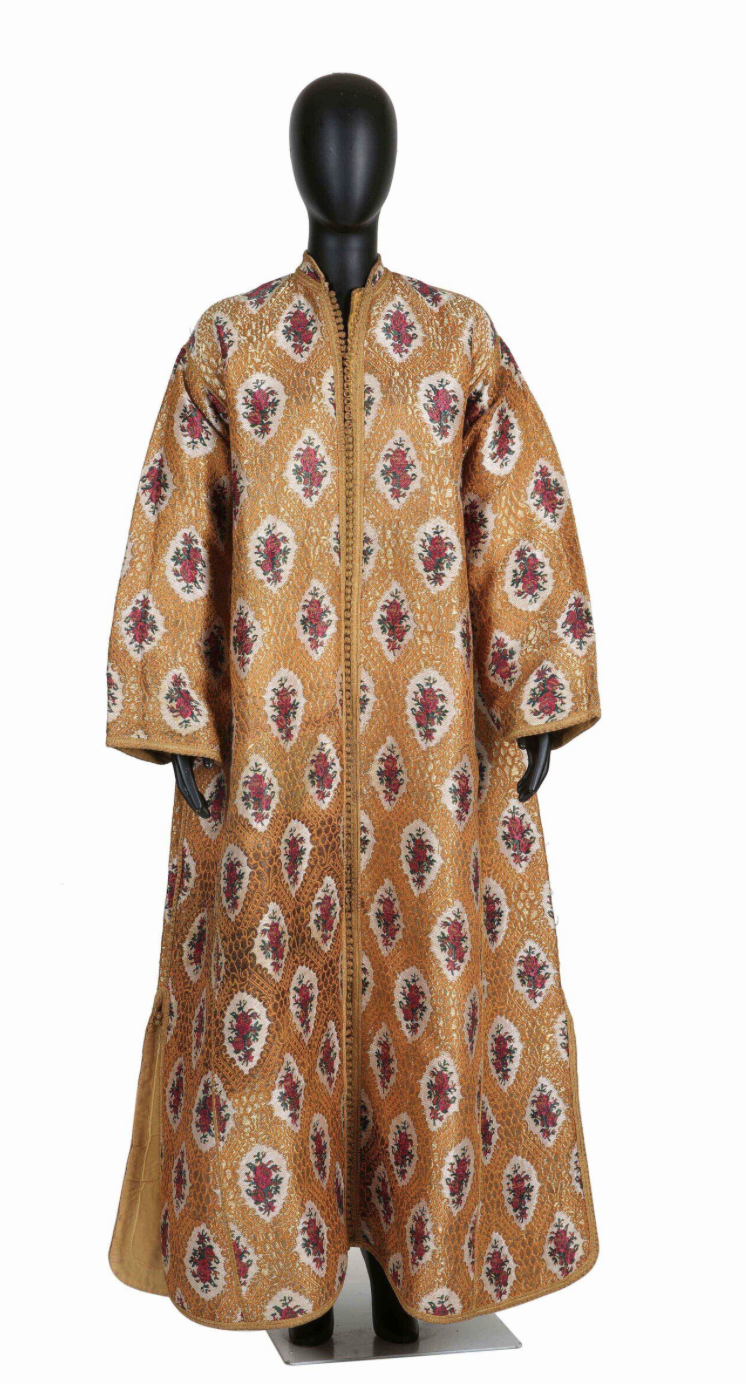

Brocade Silk Robe, Morocco (possibly Fez), c. early 20th century; Acc.No: ZI2021.500911 MOROCCO; Source: The Zay Initiative Collections, Link

Embellished Velvet Robe, Morocco (possibly Fez), c. early 20th century;Acc.No: ZZI2022.501004 MOROCCO; Source: The Zay Initiative Collections

Today, the kaftan (qaftan) coexists with other articles of clothing that express various identities and has been reinterpreted by contemporary fashion designers. A premier fashion event in Morocco on kaftans (qaftan), highlights the garment’s continued importance. The kaftan’s versatility is also evident in Yemen, where it serves different purposes depending on the region’s climate, worn as a sheer layer in hot areas or over pants a pair of trousers in cooler regions.

Conclusion

The kaftan is a garment steeped in history, tradition, and cultural significance. From its origins in Central Asia to its widespread adoption across Eurasia, the kaftan has evolved into various regional styles, each reflecting the unique cultural exchanges along the Silk Roads. Its role as a symbol of status, diplomacy, and national identity underscores its enduring legacy. Today, the kaftan continues to be a beloved and iconic garment, celebrated in fashion and cultural events worldwide. Its journey from a practical robe to a symbol of elegance and cultural heritage exemplifies the rich tapestry of human history and the intricate connections between diverse cultures.