Manila Shawl: From Left to Right and Centre

The (Manila_shawl), popular as “(Mantón_de_seda)” or “(Canton_shawl)“ has a fascinating history that spans several continents and cultures. Its journey can be traced back to Guangzhou, China, where it was first produced in the late 18th century. Made from silk and wool, these shawls were intricately woven with colourful patterns and designs.

Honestly, I think it is one decorative item that could truly be a strong contender of global cultural mapping for early modern history, the history of consumerism as well as the rise of appropriation of textiles in Europe. However, to understand the spread of its fame, one needs to look away from aesthetics and ethereal beauty of the product and focus on a more practical and cold aspect – trade.

Global history from the 17th and 18th centuries up to the early and mid 20th century, is rife with trade monopolies leading to colonization. The East India Companies of Great Britain, France, the Netherlands, and Spain were the few famous ones amongst others. Be it spices or textiles, slaves or animals, European necessity led them to invest and embark in grand voyages to the lands famous in the legends and were mentioned in the classics. From the armadas on the sea to the exploratory journeys on land all culminated to weave a romantic tale of these faraway lands and built a sense of exoticism around the wares they brought back – Chinese textiles being one of them.

Six fold screen depicting the “Arrival of a Portuguese Ship in Nagasak”i by an unknown artist, c. 1600-1630; Acc No803-1892; Source: East Asia Collection, V&A, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O121082/arrival-of-a-portuguese-ship-screen-unknown/

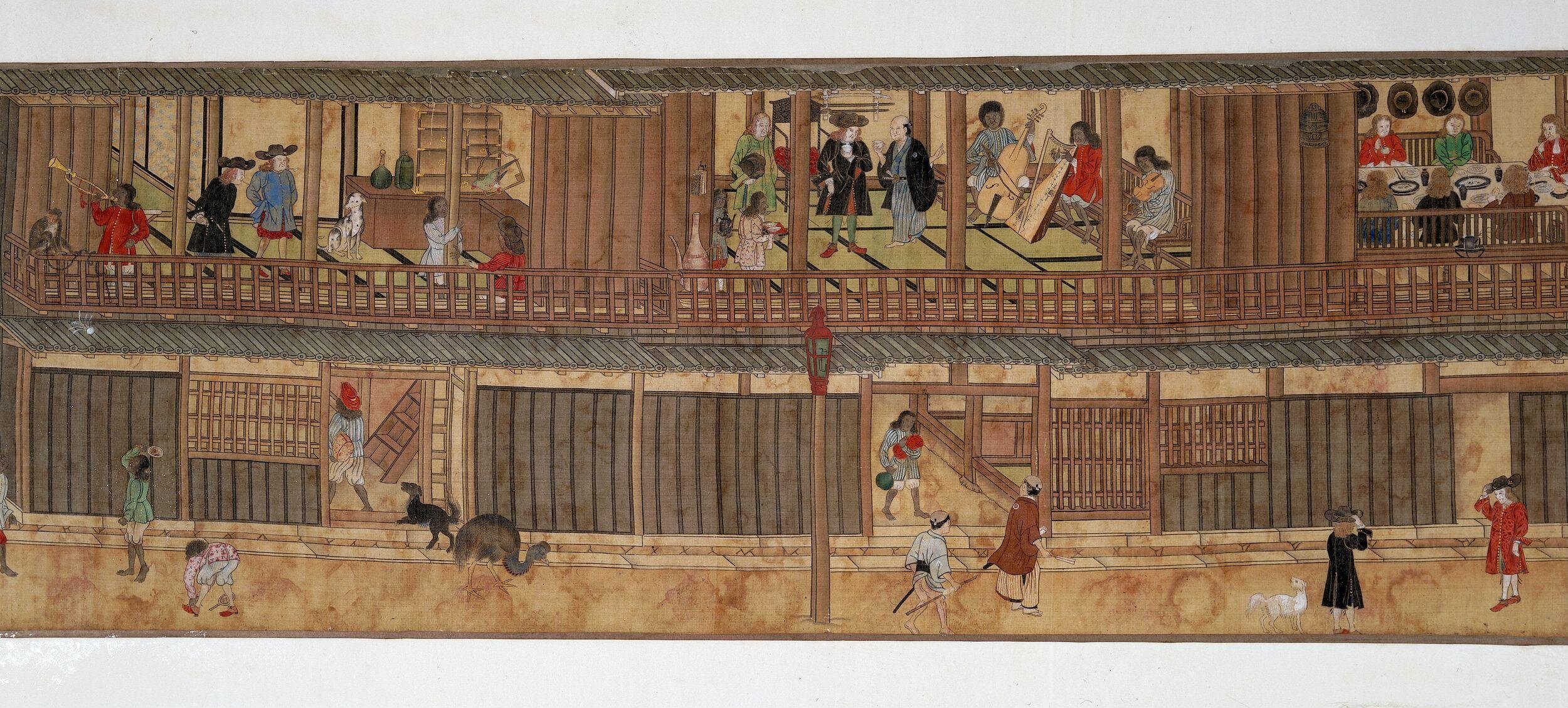

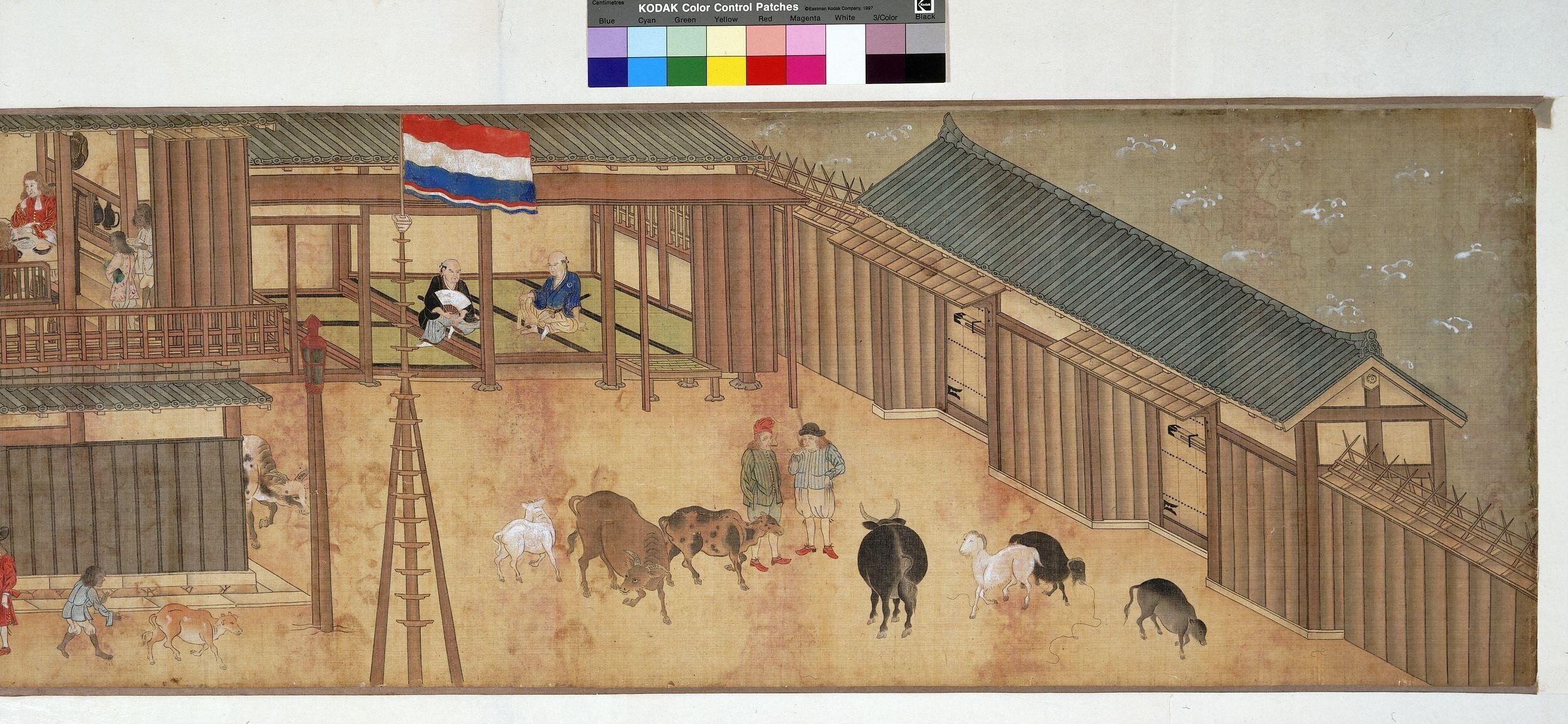

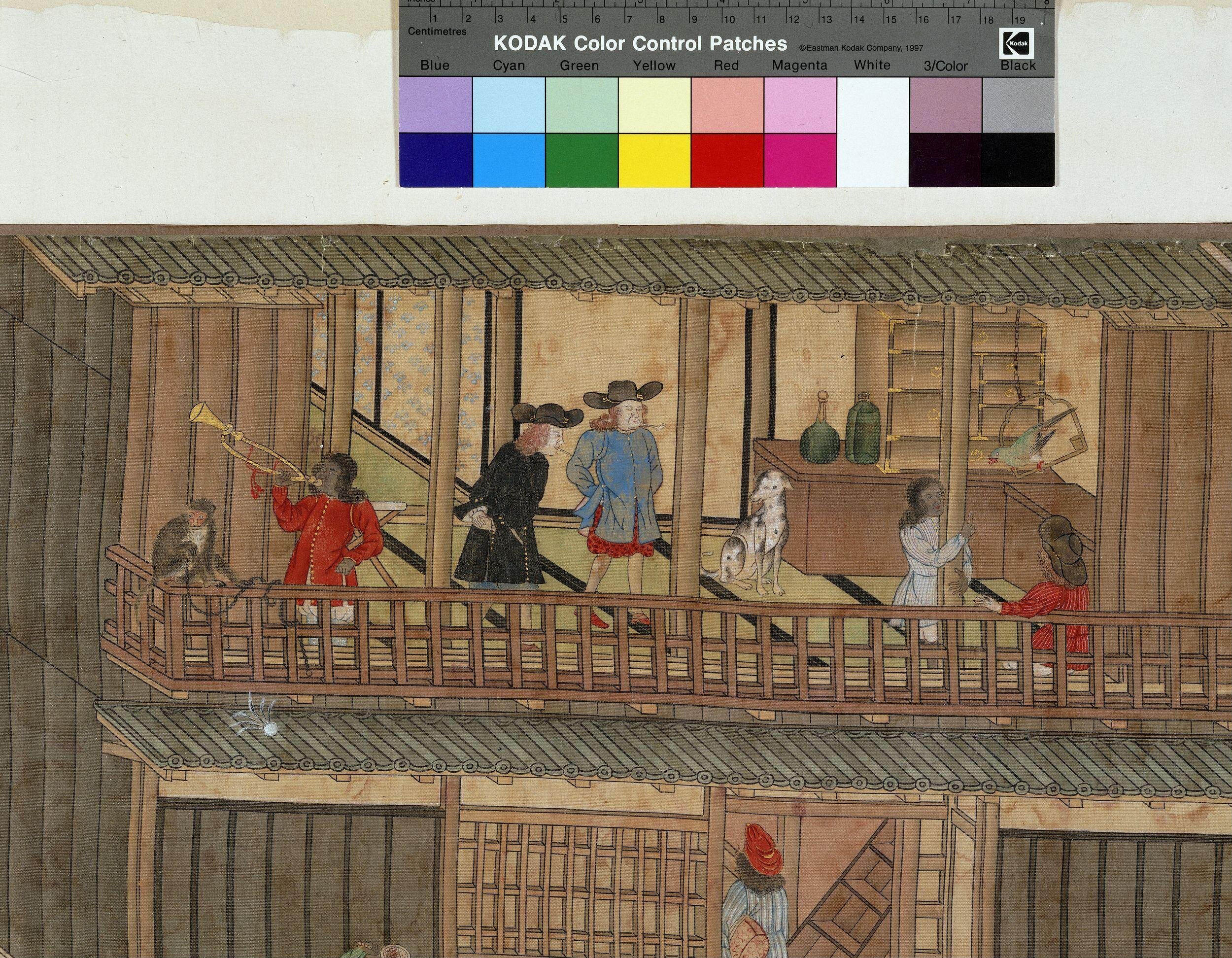

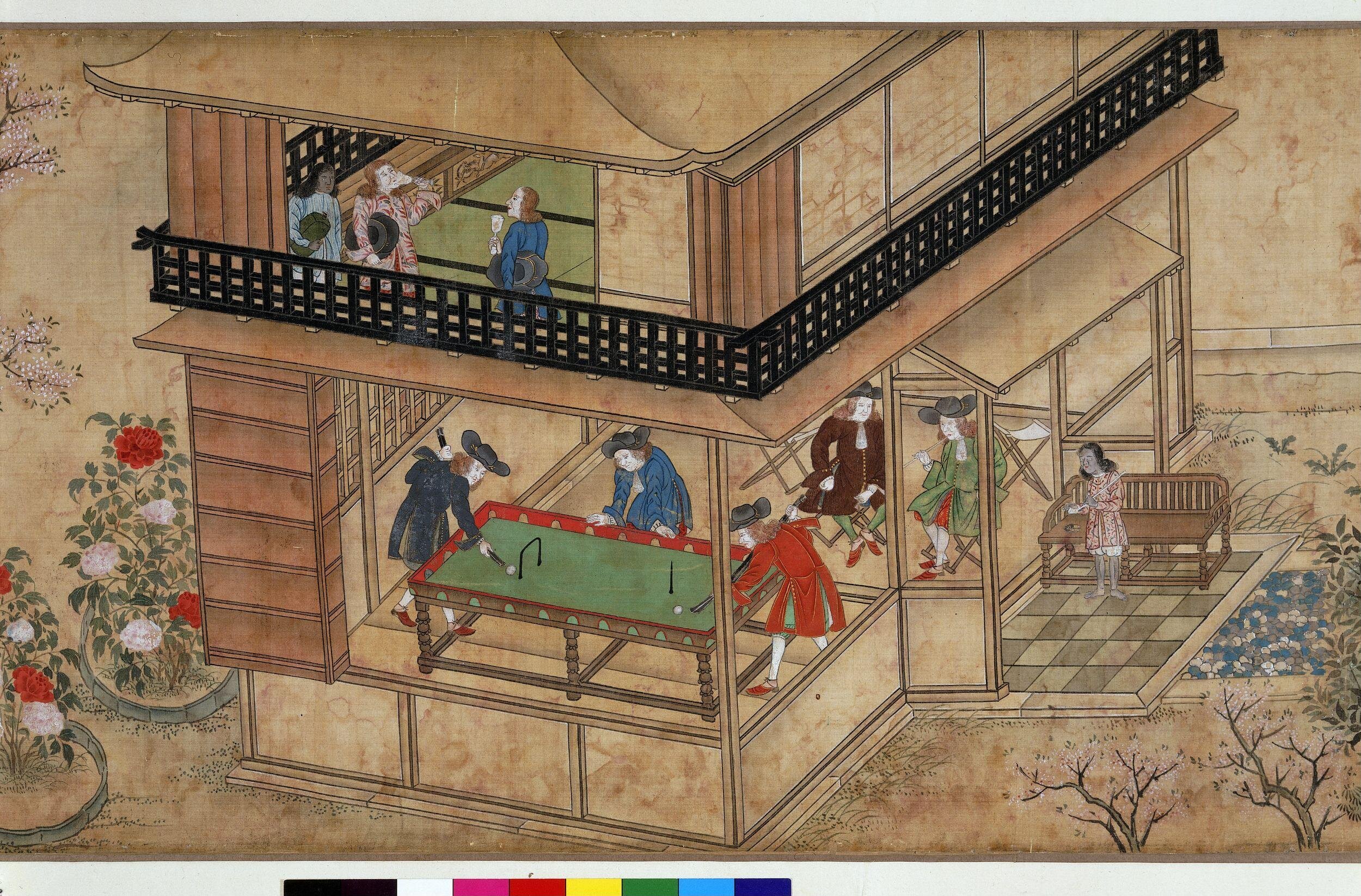

It was not long before Chinese textiles gained favour in the eyes of the Europeans and became popular amongst the elites of the society not just due to their exoticism but for other good reasons such as their craftmanship, uniqueness, finesse, novelty, quality etc. Although not completely closed off to Europe as many may think, Japan was in fact a closed chapter for most European nations with the only exception of the Dutch East India Company, that too under very close scrutiny and control. Their limited access extended only to an artificial island called Dejima in the Nagasaki Bay. However, having a watering hole in the Pacific close to China and the rest of the Far East opened an immense opportunity for them.

Hand-scroll depicting the Dutch factory at Dejima by unknown artist/s, c. 1800; Acc No D151-1905; Source: East Asia Collection, V&A, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O109070/handscroll-unknown/

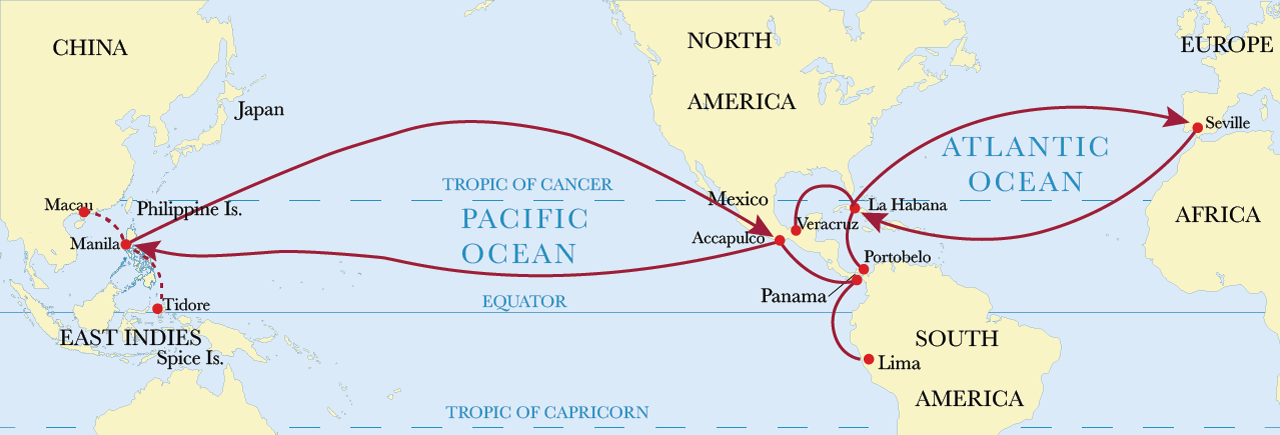

To complete the Spaniards who already had a strong hold in South and Central America, it wasn’t long before Southeast Asia was cramming with Europeans. Spain occupied the Philippines and the ware of the Far East started becoming readily available to be traded. It was through these Spaniards that the Manila_shawl made its way to Europe. It was first introduced in Europe by the Spanish. A shawl that was originally made in Guangzhou or Canton in China, made its way to Europe through the port of Manila, in the Philippines travelling across the Manila Galleon Route that was active from1565 to 1815 and spanned from China to Philippines to Mexico to its final destination at Seville in Spain.

Manilla to Accapulco to Seville Galleon trade route; Source: The Kaleidoscope of Fashion, Modes Muzejs, Riga https://www.fashionmuseumriga.lv/eng/kaleidoscope/manila/

View of Manila by Johannes Vingboons, c. 1665; Source: Atlas of Mutual Heritage and the Nationaal Archief, the Dutch National Archives, https://www.wikiwand.com/en/History_of_Manila#Media/File:AMH-6763-NA_Bird’s_eye_view_of_Manila.jpg

View of the city of Seville and Guadalquivir river by Alonso Sanchez Coello, c. 16th century; Source: Catálogo de publicaciones del Ministerio and Catálogo general de publicaciones oficiales, MiniStEriO DE EDucación, cultura y DEPOrtE, https://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/museodeamerica/dam/jcr:695d38bc-3384-4a9e-81e4-b6f7aa3c852a/folleto-del-museo-de-am-rica-en-lectura-f-cil.pdf

This is where the plot thickens and becomes far more interesting. In the Philippines, the shawl gained its popularity mostly amongst the colonial populace before being accepted by the local elites and wealthy who used it as a status symbol. These shawls were also used as gifts and traded for other goods, further spreading their influence.

With elements and iconographies of symbolic meanings steeped in Far Eastern culture specially Buddhist and Taoist and such as dragons, pagodas, flora and fauna – chrysanthemum, peony, lotus, frogs, toads, bats, butterflies, and cranes – social scenes with men and women in local costumes such as hanfu and kimono set against the backdrops of both idyllic country sides as well as bustling cities could be seen in some of the earliest surviving examples of these shawls.

Manila Shawl in The Zay Initiative Collection; Acc No: 2. ZI1995.500900.1 ASIA FB; Source: https://thezay.org/product/zi1995-500900-1-asia-silk-hand-embroidered-shawl-with-long-fringes-china/

Los mantones de Manila by Fernando Fader, c. 1914; Acc No: 1757; Source: Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (Buenos Aires), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fernando_Fader_-_Los_mantones_de_Manila_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg https://www.bellasartes.gob.ar/coleccion/obra/1757/

However, as they passed through the colonies of Mexico and the Latin Americas one could notice very gradual yet spectacular transformations in them over time. Much the pashmina from Kashmir, the popularity of these shawls amongst the European colonisers in Central and Latin Americas were acutely felt in the local market through their growing demand.

Shawl, Guandong c. 1880-1920; Acc No: FE.29-1983; Source: East Asia Collection, V&A, London, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O24338/shawl/

El Jaleo, by John Singer Sargent, c. 1882; Acc No: P7SI; Source: Spanish Cloister, Isabella Stewart Gardener Museum, Boston, https://www.gardnermuseum.org/experience/collection/13259#

This cry of help was answered by the women of the indigenous native population. They learned the art of European embroidery to help produce the local variants of these shawls thus contributing to the local economy. It was only natural for a piece of costume that had such a positive effect on their economy to be incorporated as a part of their traditional dress to the point of being auspicious enough to be worn at religious ceremonies. It was not long before the original oriental iconographies associated to these shawls gave way to more occidental and indigenous native one. This was the first phase of transformation in accordance with the demands of the local markets. The surviving examples of this period could be identified by their more native American iconographies and symbolisms through the motifs eg. geometric shapes, bolder colours symbolic to their culture, unapologetically bigger sizes in both the shawls and the motifs etc.

Despite the local production in the colonies of the New World, a large proportion of these shawls continued to be manufactured in China for specifically for export purpose and the trade continued to boom. Unfortunately, with Mexico’s independence in 1815 the Manilla Galleon Route was dissolved thus bringing this once lucrative trade to a crashing halt.

Manila Shawl in The Zay Initiative Collection; Acc No: 2. ZI1995.500900.2 ASIA FB; Source: Link of https://thezay.org/product/zi1995-500900-2-asia-silk-hand-embroidered-shawl-with-long-fringes-china/

Manila Shawl in The Zay Initiative Collection; Acc No: 2. ZI2022.501001.4ASIA; Source: https://thezay.org/product/zi2022-501001-4-asia-silk-hand-embroidered-shawl-with-long-fringes-china/

However, some poor and defective quality Chinese fabrics with their original oriental iconographies were still in circulation in Spain specially amongst the cigar making community in Seville. These were possibly from the tobacco packaging from the Philippines. The cigarrera women would be often seen using them as ornaments for decorative purposes. These women monopolized the responsibility to popularize them in mainland Europe.

La Cigarrers by Gonzalo Bilbao Martinez, c. 1915; Source: Museo Bellas Artes De Sevilla, https://bit.ly/3LHsGJjU

Cigarreras of the Royal Tobacco Factory in Seville, c. 1920; Source: The Kaleidoscope of Fashion, Modes Muzejs, Riga https://www.fashionmuseumriga.lv/eng/kaleidoscope/manila/

A once vibrant trade that had almost died with Mexico’s independence was about to breathe anew, but unfortunately in 1898 Spain lost the Philippines and the hope was dashed. This brought about the second phase of transformation. Instead of giving up women embroiders set up workshops around the villages of Seville to keep up with the European demands. Again the oriental imageries and colour pallet gradually morphed itself into the cheerful Andalusian identity with sporadic incorporation of its original motifs. The attachment of the fringes – a very Moorish, Arab, and Romani feature – to the shawl was the final stamp to make it uniquely Spanish in nature.

Present day examples of newly manufactured Manila_shawls are primarily based on the models of the first quarter of the 19th century with an enormous diversity in its style and aesthetics.

In conclusion, the history and journey of the Manila_shawl from Guangzhou, China, through the Philippines to South and Latin America, and then to Spain and Morocco, is a testament to the global exchange of ideas and culture. The influence of both indigenous tribes and colonial populace on the shawl’s design, as well as the influence of Moorish, Arab, and Romani culture, has resulted in a unique and beautiful textile that continues to be celebrated today.

Links:

https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/traditional-mexican-dress

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O528731/manilla-fashion-design-worth-jean-charles/

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O24338/shawl/

https://dressworld.hypotheses.org/382

https://www.museoreinasofia.es/en/collection/artwork/bailarina-dancer-3

https://www.fashionmuseumriga.lv/eng/kaleidoscope/manila/

https://waiyukkennedy.wordpress.com/2014/01/03/manila-shawl-in-the-va/

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mgtr/hd_mgtr.htm

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/expa/hd_expa.htm

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O109070/handscroll-unknown/

https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/japans-encounter-with-europe-1573-1853/

https://www.andalucia.com/cities/seville/tobacco-factory-carmen

Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k6QG_RNDAOc

https://zapatosdebaileflamenco.com/blog/historia-del-manton-de-manila/