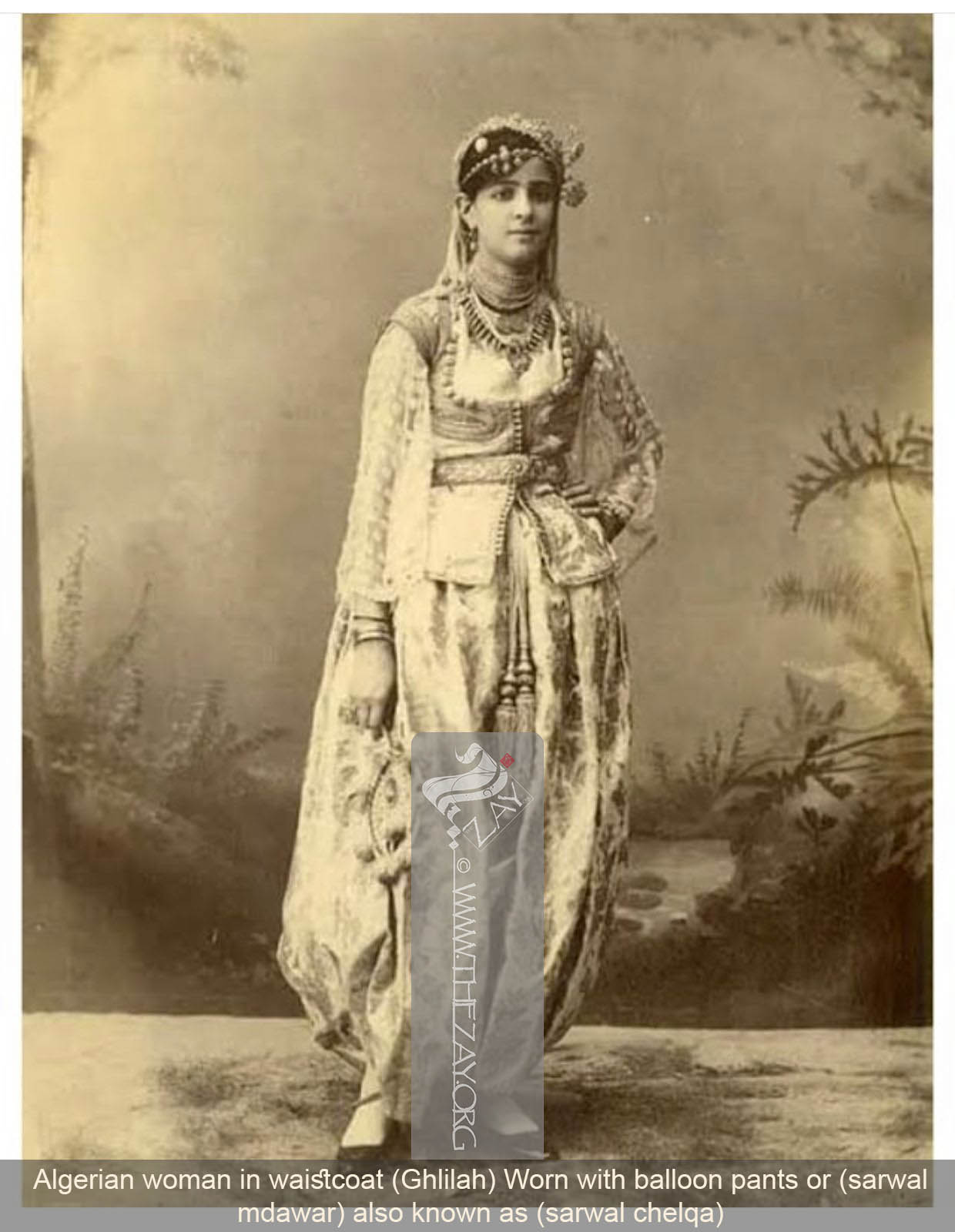

Object NoteInterestingly, an almost exact example of this Algerian vest (

ghlilah

Ghlīlah: (diminutive of the Arabic: ghlālah: waistcoat, synonyms: sadār, sadrīyah, sadārah, strah) short or medium length waistcoat worn generally with balloon pants (sarwāl mdawar) also known as (sarawāl chlqah).) can be found at the Collection of

Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme. Object History The term

ghlilah

Ghlīlah: (diminutive of the Arabic: ghlālah: waistcoat, synonyms: sadār, sadrīyah, sadārah, strah) short or medium length waistcoat worn generally with balloon pants (sarwāl mdawar) also known as (sarawāl chlqah). is a diminutive of the Arabic word ghlalah referring in general to undergarments worn by men or women across social strata and religious spectrum, uniting them across ethnic and religious differences.

This Algerian 19th-century female vest/waistcoat (

ghlilah

Ghlīlah: (diminutive of the Arabic: ghlālah: waistcoat, synonyms: sadār, sadrīyah, sadārah, strah) short or medium length waistcoat worn generally with balloon pants (sarwāl mdawar) also known as (sarawāl chlqah).), is of white and gold brocaded silk in floral design, featuring repeated floral motifs in gold across the entirety of the textile, and extensively hand embellished in passementerie which consists of gold thread braids (

fatlah

Fātlah: (Arabic: fatala: to twist/twine, pl. fātlāt/ftūl), in the UAE colloquially, it refers to braids in (tallī) work. The braid or strand resembles a running stitch, where the effect is attained by continuously looping metallic thread with silk, cotton, or synthetic thread. ) appliquéd or couched to the ground fabric. The metal thread embroidery, typically of gold or silver, would have been sourced from local Jewish silversmiths, craftsmen who likely settled in the Maghreb with the exodus from Andalusia following the fall of Granada, the last Muslim-controlled city in southern Spain, in 1492.

It is, sleeveless, open in front with a large rounded neckline, closing with two small braided buttons in gold thread. It has a pocket slit at the waist on the right side, and it is fully lined in white silk.

The edges of the neckline and the armholes are reinforced on the inside with woven cotton ribbon while on the outside the armholes are hemmed with couched trimmings of gold thread (

fatlah

Fātlah: (Arabic: fatala: to twist/twine, pl. fātlāt/ftūl), in the UAE colloquially, it refers to braids in (tallī) work. The braid or strand resembles a running stitch, where the effect is attained by continuously looping metallic thread with silk, cotton, or synthetic thread. ). The two rows of passementerie outline the short, shoulder-length sleeves, and one line traverses the shoulders and continues along the entirety of the open frame around the

yoke

Yoke: (Synonym: Bodice_Yoke), a structured pattern fitted at the shoulders defining the structure of women’s garments. Introduced in c. 1880s it defines the transition between the upper and lower parts of the garments and can now be found stitched-in where the blouse is separated from the skirt by a horizontal seam. or neckline. These function not only as adornment but also as a means of concealing and reinforcing the seams of the garment.

The neckline is edged with 8 braided gold thread buttons on each side. While at the level of the chest, on both sides, it is embellished with an application of trimmings of gold threads filled in sequins, in an oval, elongated triangular shape known as the “evil eye” motif.

Ranging from a triangular shape to a more oval-shaped it makes reference to the evil eye, which has been a protective symbol in the Arab world since antiquity. While not exclusive to any one religious canon, the evil eye became integrated into Jewish and Muslim beliefs and practices and thus maintained relevance within North Africa and the Arab world across the centuries. While the persistence of this motif into the 19th century indicates its assertion of local sartorial styles and cultural significances implicating economic differences within Algerian society since the quality and form of the embroidered triangular motifs varied based on the wearer’s economic and social standing.

In contrast to the more luxurious exterior fabric, the interior lining, customarily, however, not in this example, consists of cheaper printed cotton chintz or calico fabrics. The plain-woven, block-printed fabrics originated in India and were exported to Europe beginning in 1600, becoming fashionable dress in Europe by the mid-1600s 1600s.

Elite women could afford the more heavily adorned caftans and

ghlilah

Ghlīlah: (diminutive of the Arabic: ghlālah: waistcoat, synonyms: sadār, sadrīyah, sadārah, strah) short or medium length waistcoat worn generally with balloon pants (sarwāl mdawar) also known as (sarawāl chlqah). that they wore for daily use, while less affluent women possessed

less richly adorned garments that were reserved for ceremonial events and festival days.

More DetailsThe scarcity of documents prior to the French colonial period in Algeria poses an obstacle to reconstructing the temporal transformation of women’s costumes. However, one of the earliest Western texts to remark on a dress in Algiers is by Spanish Friar Diego de Haëdo published in (1612), recorded observations of society in Algiers from 1578 to 1581. During that time the ghlilah

Ghlīlah: (diminutive of the Arabic: ghlālah: waistcoat, synonyms: sadār, sadrīyah, sadārah, strah) short or medium length waistcoat worn generally with balloon pants (sarwāl mdawar) also known as (sarawāl chlqah). is described as a waistcoat generally of satin

Sātin: (Arabic: Zaytuni: from Chinese port of Zayton in Quanzhou province where it was exported from and acquired by Arab merchants), one of the three basic types of woven fabric with a glossy top surface and a dull back. Originated in China and was fundamentally woven in silk., velvet, or damask

Dāmāsk: (Arabic: Damascus – a city in Syria), is a luxurious fabric woven with reversible patterns typically in silk, wool, linen, or cotton. Originating in China, the fabric was perhaps introduced to European traders at Damascus – a major trading post on the Silk Road with a thriving local silk industry. , that fell to mid-leg length and featured a wide neckline secured just above the breasts by large gold or silver buttons. The garment can display both sleeveless and elbow-length sleeves. At certain times the term connected directly to the function of the garment as a support for a woman’s bosom, and was customarily worn on top of a sheer-sleeved undershirt, together with full-length balloon length (sarwal

Ṣarwāl: (Farsi: shalvār; Synonym: salwar

Salwar: (Farsi: shalvār; Synonym: ṣarwāl, shirwāl ), trousers featuring tapering ankles and drawstring closure of Central Asian origin. They disseminated in the Indian subcontinent between c.1st-3rd century BCE. Although exact period of its arrival in the Arab world is disputed their widespread adoption is confirmed from the 12th century.

, shirwāl), trousers featuring tapering ankles and drawstring closure of Central Asian origin. They disseminated in the Indian subcontinent between c.1st-3rd century BCE. Although exact period of its arrival in the Arab world is disputed their widespread adoption is confirmed from the 12th century.

mdawar) also known as (sarwal

Ṣarwāl: (Farsi: shalvār; Synonym: salwar

Salwar: (Farsi: shalvār; Synonym: ṣarwāl, shirwāl ), trousers featuring tapering ankles and drawstring closure of Central Asian origin. They disseminated in the Indian subcontinent between c.1st-3rd century BCE. Although exact period of its arrival in the Arab world is disputed their widespread adoption is confirmed from the 12th century.

, shirwāl), trousers featuring tapering ankles and drawstring closure of Central Asian origin. They disseminated in the Indian subcontinent between c.1st-3rd century BCE. Although exact period of its arrival in the Arab world is disputed their widespread adoption is confirmed from the 12th century.

chelqa), all of which are concealed under an overall body cloak (hayk) when out in public. Though by the 19th century, the form-fitting vest/waistcoat served as a common, everyday item of clothing for the majority of Algerian women. According to author Leyla Belkaïd this garment is believed to have originated in the Eurasian steppes during antiquity and was introduced to Eastern and Northern Europe in the 13th century B.C.E. by the Scythians, a Central Asian semi-nomadic empire. While according to François Boucher, the vests/waistcoats became common in the regions of Central Asia and Northern Europe during antiquity, the costume did not become integrated into the Mediterranean wardrobe until much later. Asserting that, nearly a millennium passed before the Byzantines appropriated the large open-front qaftan

Qafṭān: (Persian: khaftān, Pl. qafāṭin, synonyms: ghandurah

Ghandūrah: (Arabic, pl. qanādīr, synonyms: qandurah, darā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, qaftan, mqta’, thawb or tobe), a loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamis

Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences., qandurah

Qandūrah: (Arabic, pl. qanādīr, synonyms: ghandurah

Ghandūrah: (Arabic, pl. qanādīr, synonyms: qandurah, darā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, qaftan, mqta’, thawb or tobe), a loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamis

Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences., darā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, qaftan, mqta’, thawb or tobe

Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ), a loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamis

Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. , drā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, kandurah

Kandūrah: (Arabic: qandūrah, pl. kanādīr, synonyms: ghandurah

Ghandūrah: (Arabic, pl. qanādīr, synonyms: qandurah, darā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, qaftan, mqta’, thawb or tobe), a loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamis

Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences., qandurah

Qandūrah: (Arabic, pl. qanādīr, synonyms: ghandurah

Ghandūrah: (Arabic, pl. qanādīr, synonyms: qandurah, darā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, qaftan, mqta’, thawb or tobe), a loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamis

Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences., darā’ah, dishdāshah, jalābah, jallābīyah, qaftan, mqta’, thawb or tobe

Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ), a loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamis

Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. , dra’ah, dishdāshah, jallābīyah, jalābah, jillābīyah, qaftan, mqta’, thawb or tobe

Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ) loose, short or long sleeved, shirt like (qamis

Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

) tunic with frontal neckline opening, worn by both sexes. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences., mqta’, thawb or tobe

Tobe: (Arabic: thawb, Pl. Athwāb/thībān), can be pronounced thawb or thobe based on locale. The standard Arabic word for ‘fabric’ or ‘garment’. It can refer to a qamīs-like tunic worn by men and women in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the southern and south-western ports and islands of Iran, and some countries in East and West Africa. More specifically, it can refer to the square-shaped Bedouin overgarment worn by women. ) loose, short or long-sleeved, shirt like (qamis

Qamīṣ: (Possibly late Latin: Camisia – Linen Undergarment; Synonym: Kamiz), a traditional loose fitting long tunic or shirt worn by both men and women in South and Central Asia and the Arab world. Typically extending below the waist it is usually paired with a pair of trousers.

) tunic with frontal neckline opening. Each Arab region has a different term for what is essentially a similar garment with various small differences. worn by Persian soldiers and fashioned a new open-front coat which became à la mode during the 12th century C.E. At the same time, the pre-existing Muslim empires, including the Ottoman Empire (1299-1922/23), established in the Mediterranean were also pulling from Persian costuming and importing fine Persian silks to develop their own variations on the open-front tunic. Thus, when the Ottomans expanded their far-reaching empire to the regions of the Maghreb during the early 16th century, Egypt (1517) and Algeria were the first of the North African states to come under the Ottoman Empire followed by Libya (1551) and Tunisia (1574), heavily embroidered waistcoats were readily adopted by Algerian men and women alike and gradually diverged into distinct garments, including the ghlilah

Ghlīlah: (diminutive of the Arabic: ghlālah: waistcoat, synonyms: sadār, sadrīyah, sadārah, strah) short or medium length waistcoat worn generally with balloon pants (sarwāl mdawar) also known as (sarawāl chlqah). and (rmlah), as local tastes, techniques, and designs were incorporated. The most elaborate embroidery traditions were found in Algeria’s coastal cities, where Mediterranean trade and influences combined to create the multi-cultural mélange that became characteristic of urban wear in Algeria, and became popular among all women of Algiers. In this way, the garment represented a point of visual, cultural, and fashionable commonality amongst the women of Algiers which united them across ethnic and religious differences. Haëdo noted two versions of the women’s waistcoat ghlilah

Ghlīlah: (diminutive of the Arabic: ghlālah: waistcoat, synonyms: sadār, sadrīyah, sadārah, strah) short or medium length waistcoat worn generally with balloon pants (sarwāl mdawar) also known as (sarawāl chlqah).: the “modest” version, which evolved from a local Algerian model of the 15th century, and the “distinguished” version, which was closer to the Turkish garment. The modest local variation featured a higher, straight neckline, while the distinguished Ottoman-influenced version sported the deeper, curved neckline seen in extant in examples from the 19th century. Both garments used a system of detachable sleeves that allowed the cut to be altered depending on the weather. Link

- Haëdo, Diego de. Topografia e historia del Argel, Valladolid, 1612, French translation by Berbrugger and Monnereau, in Revue africaine, 1870-71. Reprinted by Jocelyne Dakhlia. Saint-Denis: Editions Bouchene, 1998.

- Leyla Belkaïd, Algéroises: histoire d'un costume méditerranéen (Aix-en-Provence: Edisud, 1998)

- François Boucher, Histoire du costume en Occident de l’Antiquité à nos jours (Paris: Flammarion, 1983)

- Snoap, Morgan, "Algerian Women's Waistcoats - The Ghlila and Frimla: Readjusting the Lens on the Early French Colonial Era in Algeria (1830-1870)" (2020). Honors Program Theses.

- Pascal Pichault , The traditional Algerian costume, Maisonneuve and Larose,2007 (ISBN 2-7068-1991-X and 978-2-7068-1991-9, OCLC 190966236